by Manuel Henríquez Lagarde (November 2003)

Spanish original appeared in a Jiribilla Number 11

http://www.lajiribilla.cu/2003/n130_11/130_05.html

Though in many of his writings, Noam Chomsky had repeatedly referred to Cuba, he had never visited the island. According to the “essential” or “imprudent” American, as some call him due to his acute and consistent critical views on the US establishment, though his relationship with the island dates back to the beginnings of the Revolution, that relationship had so far been abstract. It was only through documents or history books. In fact, he is the only one in his family who had not gone through the experience of living in or visiting the island.

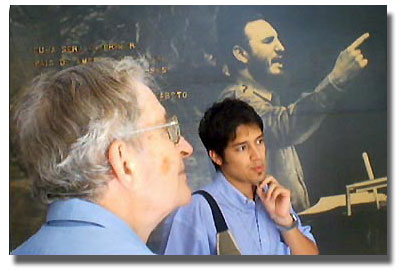

La Jiribilla photo

In order to come to Cuba for the first time, the US academic had to present a bunch of documents to prove that CLACSO, the organization inviting him to participate at a Havana conference, was a network of Social Sciences research and teaching centers that gathers 144 such centers in Latin America and the Caribbean, rather than a kind of screen for the Cuban government or a covert travel agency which made it easier for Americans to illegally travel to Havana.

In order to convince State Department officials, Chomsky had no choice but to present a report at the US embassy in Buenos Aires, certifying that CLACSO was a legally registered organization.

When he already had the authorization to travel, he was warned: “Well, but you cannot spend a penny in Cuba”. With respect to that, Chomsky presented a sworn statement.

When he was about to buy the plane ticket, according to the travel agency, the form that the US Treasury Department sent him was inadequate. The professor called Washington to ask for a new form where he promised not to spend a penny in Cuba. So that the State Department issued the permit, he also needed to prove that he belonged to a US academic institution: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Arrangements got complicated again when US government officials learned that Chomsky was planning to travel to Cuba with his wife Carol Schatz. He had to make the same complicated travel arrangements for her.

Chomsky’s wife spent three weeks to get her permit. And when at last it seemed that everything was ready for their trip, a government official sent an email warning Noam Chomsky that he could not travel on behalf of an institution, because if any problem occurred, they needed to know who was responsible. CLACSO’s Executive Secretary took responsibility and covered his guest’s expenditures.

Once they overcame the problems derived from restrictions imposed by the US government to prevent Americans from traveling to the island, the prestigious linguist of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology finally was able to arrive in Havana to participate in the CLACSO event from October 27th through 31st.

A encounter with history

Following his master lecture at the CLACSO gathering, the first thing Noam Chomsky did in Havana was to have an encounter with history. At 11 a.m. on the 29, the US intellectual visited the National Literacy Museum, a small building located in Ciudad Escolar Libertad, formerly known as Columbia, the Batista regime’s armed forces main headquarters.

Located across the former headquarters, and just a few meters from the mansion that the dictator occupied when he was a General, the small institution treasures, among other objects, uniforms worn by literacy campaign participants, books, manuals, a blackboard hit by bullets shot during the Bay of Pigs invasion, pictures and personal belongings of the teachers murdered by counterrevolutionary gangs during the literacy drive and the Chinese made lamps used at night in the most remote places of the Cuban countryside.

Noam Chomsky, accompanied by his wife, watched the different objects on display and listened to details of the Cuban educational feat narrated by the Museum’s Director.

At the modest institution’s library, the US intellectual and his companions met a group of Ecuadorian visitors who were conducting research on the Cuban experience.

The Museum’s Director took the opportunity to say that the campaign had not only been done by Cubans. One Ecuadorian and also US students and teachers participated in the drive. “One of the US teachers who taught how to read and write in Cuba, said the Director, died in August, this year.”

The US teacher, according to history, not only devoted her efforts to teach, but also she was also responsible for 14 students who had become educators during the campaign. She was in Cuba with her two children, her oldest daughter – a 12 year old girl – also taught how to read and write.

“That is why, said the Director, we are helping all nations which are requesting assistance in the area of literacy to, up to a certain extent, contribute to teach the world’s 800 million illiterates how to read and write.”

Cuba is cooperating in the area with several countries, including Mexico, Nicaragua, Haiti, Guinea Bissau and New Zealand.

Later, in one of the museum’s halls, Chomsky received a detailed explanation about the campaign from one of his main protagonists: Armando Hart, who was Acting Education Minister at the time.

Hart explained that before beginning the drive, the first thing revolutionary government leaders did was to tour the country from one tip to the other. Everywhere, people essentially asked for two things: teachers and doctors.

The first measure to take was to look for resources to be able to carry out the campaign. In Cuba at that time, 50 percent of school aged children didn’t have schools and 9 million teachers were facing a similar situation. 5000 classrooms could be created with the resources that the Education Ministry had at that time. When Fidel knew about it, he came up with the idea of paying teachers half their salaries and creating twice as many classrooms. In order to carry out the literacy campaign, the government first needed to get rid of the main source of illiteracy: the lack of schools.

“Then, Fidel said at the United Nations in 1960 –recalled Hart, while Chomsky and Carol watched him attentively from their chairs located around a fan-, that Cuba would get rid of illiteracy in 1961. A popular education council was set up, including all of the country’s grass roots organizations. Teachers mainly worked to guide the 100 thousand volunteer teachers and other people who had 6th grade whom were asked to teach someone to read and write. Then, we had a slogan: “Each illiterate must have a teacher, each teacher must have an illiterate.”

The campaign that kicked off on January 1st, 1961, wound up on December 22nd, the same year. Cuba declared it was free of illiteracy in only nine months.

Before leaving the institution, Chomsky and his wife went through some of the 700 thousand letters that people who had been taught how to read and write had written and sent to Fidel Castro. One of them specially called their attention, a letter sent by an 86 year old peasant and the one sent by a 102 year old woman, as well as another one which read:

Fidel: "I never went through the experience of being

Cuban until I learned how to read and write.”

In Old Havana

When Chomsky exchanged views with journalists or readers, he reminded me of one of those grand simultaneous chess players. He always had an answer for each person who requested his explanation about a current issue. Chomsky speaks slowly and his gestures are scarce and measured. He expresses his opinions, using that personal style through which his mastery of political events mixes with his profound wisdom of the history of the United States. It’s not strange that only one of his answers could become an entire lecture.

Something like that occurred during the launching of the book Chomsky at La Jornada, -- a compilation of writing by the US political expert published in the Mexican newspaper bearing the same name -- held at the portico of a colonial building, the former Palacio del Segundo Cabo, housing headquarters of the Cuban Book Institute, in the heart of Old Havana.

After the presentation by the President of the Cuban National Assembly, Ricardo Alarcón, who along with Eduardo Galeano and Spanish writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, who died recently, wrote the book’s prologue. Following a few words by Chomsky himself, the US political expert agreed to exchange views with an audience made up of writers, journalists, readers or curious people who were just passing by one of the city’s most-visited squares.

On that occasion, the first question was asked by Cuban novelist Jaime Saruski:

Saruski: Three days ago La Jornada published an article of yours that read at the end that it had been published at the New York Times. Does that mean that US main stream media is opening the lock it had closed for you for many years in the United States?

Another question: I understand that you are closely linked, from the point of view of your family, with someone from the Basque country. How do you see relations between the Aznar government and the Basque country?

Noam Chomsky: It was not an article published by The New York Times, but rather by The New York Times Syndicate. It’s The New York Times Corporation; one of its sections receives articles sent from different parts of the world and I’ve published many articles in that section that way. But very few newspapers inside the US would accept such articles for publication. Your view, however, is right. That means a great opening for the main stream media and is a significant change in terms of consciousness.

After September 11th, a sort of opening in US society has occurred. US society is a very enclosed society which doesn’t know much about what happens abroad, nor is it much interested in what goes on in the world. That was a disaster in the 1980’s, when the main issue was the war against Nicaragua. A large number of people in the US thought that the US government was supporting the Nicaraguan government in its war against the guerrillas. My wife and I visited Nicaragua on several occasions in the 1980’s, because my daughter and her family lived there. Friends of her, educated people, guessed that we were going to visit the contras and the reason why this occurred lied on the fact that it was always said that the US was supporting governments against guerrillas. They knew that we were a sort of people with crazy ideas and, of course, they thought for sure that we were going to visit the guerrillas.

The September 11th terrorist attacks made many people realize that it’s better to know the world more closely and the role that the US has played in it. That has helped release the consciousness of many people.

One example is that following the large demonstrations held in February against the war in Irag, The New York Times’ front page read: “Now there are two superpowers in the world: the US government and the world’s public opinion” and that includes a great part of what people think within the country in general terms.

Unfortunately, those changes haven’t had the reach they should. The case of the five Cuban political prisoners is an example. Practically nobody knows the case’s details, and the small fraction of people who know think that those five Cubans were there to spy for the island’s government and that they are linked with the downing of the airplane by Cuban aircrafts. There are numerous examples of how much we have to walk in that sense so that there is a realistic understanding of what goes on in the world and what the people’s responsibilities are in the United States. I think that at the end we’ll get to a point in which those fundamental changes will take place.

You ask about the Aznar case and the Spanish people, and I’m going to talk of the Spanish population in general terms. That relationship can be demonstrated by the fact that Aznar decided to polish Bush’s and Blair’s boots when he supported the war in Irag, even when 80 percent of the Spanish population firmly opposed the war. The world realizes that he is following orders from Texas and is not taking into account his country’s own opinions.

Following September 11, many governments of the world, influenced by the US, have realized that they have the chance to impose a tighter control over their people and increase repression, using protection against terrorism as a pretext. That is a phenomenon of global reach and for many years now repression has been very bad in the Basque country. However, we should admit that positive events have taken place in recent years because a significant level of economic independence has been achieved in the Basque country, Catalonya and in other parts of Spain. In that sense, there has been more progress in Spain than in other European countries.

With Chomsky in Pogolotti

Founded on February 24th, 1911, the Pogolotti district was the first working class neighborhood in Cuba. Located in the Havana municipality of Marianao and with an 80 percent population of workers, Pogolotti has always been famous for being a marginal neighborhood. For some time, however, Pogolotti has stopped being famous for its street fights, “santeros” or “espiritistas”. The neighborhood now boasts of its social progress and Noam Chomsky was able to watch that in his tour of the community during a great part of Thursday morning.

The renowned US intellectual was welcomed by the President of the Cuban National Assembly, Ricardo Alarcón, at the Community House and at the Senior Citizens’ Home located on 57th Street and 92nd, a site where, according to the President of Pogolotti’s People’s Council, Odalis Verana, they are holding different activities with children, youth and adults, mainly focussing on senior citizens.

In the morning, over and over again, the US linguist and political expert, who had become an improvised journalist, hounded his hosts with questions:

Are there many senior citizens in this neighborhood?

This neighborhood is characterized by having a large population of senior citizens and we are lucky to have an interdisciplinary health center, replied the People’s Council President.

When does a person is considered a senior citizen?, Carol asked.

As of the age of 60...

Chomsky and Carol looked at each other amazed and laughed.

But while walking down the district’s streets before the curious look of neighbors, Chomsky was concerned over much more serious issues.

What is a People’s Council, how do you get to be a President?

We have 16 cirumscriptions –the Council’s President explains while they walk down 55th Street-. Later, its 16 delegates are elected, they choose who will be the ones who are going to lead them and that’s how the People’s Council’s leadership is set up. There are various neighborhoods, in our case there are neighborhoods and estates.

What is the role played by the Council concerning its neighbors’ lives?, Chomsky asks.

It controls, runs administrative activities, but also gathers, coordinates and speeds up any arrangement linked with the population.

Does it render services to the population, is it responsible for schools and health centers?

Yes, and it’s also responsible for factories, enterprises, everything that is located within its jurisdiction...

What is the main source of employment here?, the political expert asks.

People go to work to other places in the city, we don’t have large factories, the President says.

In his tour, Chomsky visited a community bottled food center and the family doctor’s office located on the corner of 100th and 57th Streets. The doctor’s office is a small four room apartment located on a building’s ground floor.

He and his wife want to know everything about how this primary health center works. After numerous questions about breast feeding and attention to pregnant women, Chomsky says:

Have you had any case of malnutrition among children?

Only one -answers the doctor, whose name is Marta and must be some 30 years old-, but the case was closely linked to an associated pathology.

Do you have problems with contagious diseases?

There is a risk group, but it’s systematically being taken care of.

Tropical diseases?

There was a recent dengue outbreak, but we had very few cases.

Chomsky asks if it’s very difficult for people to have access to health care?

People come and their health needs are taken care of as soon as possible, Marta says.

Recently –Chomsky notes- I had an unstoppable nose bleed. The only place where I could go was Boston’s best hospital. I had to wait three hours for an appointment.

This is better – Carol says and smiles.

This is not paradise

Following his visit to the Hermanos Montavos primary school, where Chomsky and his companions were briefed on the most recent Cuban educational reforms, and after touring Pogolotti’s Youth Computers Club, the delegation visited the Martin Luther Kind Jr. Memorial Center.

The religious institution’s Director, Reverend Raúl Suárez, walked them down its different facilities and, later, in one of the center’s rooms he briefed Chomsky on the Center’s history and work.

Sitting in a couch, while drinking orange juice, Chomsky and Carol listened to the reverend.

We are trying to prove that the theology of liberation is not something from the past because the raison d’être of poor people still exists. The system that US religious people taught to us clashed with the Revolution’s humanistic nature. After the end of the 1960’s, 70 percent of preachers had gone to the United States.

Those of us who stayed didn’t have the theological background to face the challenges created by the new situation. Martin Luther King Jr. taught us that there is enough biblical and theological background to live faith in a socialist project much better than in a capitalist country.

We don’t have to tell you that we believe in the Revolution. The Revolution is an alternative to capitalism, that is why we have a sufficient theological basis to be part of the revolutionary process. Sometimes, I’m passionate when I uphold the Revolution, some Americans have asked me: “Then, Cuba is God’s Kingdom?”. I’ve answered with the lines of a song by a Cuban singer and song writer that sings to an ideal woman. He says: “She is not perfect, but she is closer to what I always dreamed of”. Cuba is not God’s Kingdom but has prove that Christian ideals can be met here on Earth, that we don’t have to expect a heavenly environment.

The reverend apologizes for the sermon. Chomsky nods as if he had understood him. The previous day, during his book’s launching at the Palacio del Segundo Cabo, he said: “I’m one of the many people who around the world have admired the Cuban people’s courage and commitment to uphold their independence in the light of criminal actions that date back to many years.

“Now, it’s already known, how big Cuba’s contribution to the liberation of Africa, to the liberation and development of other countries has been, such as in the case of today’s Venezuela. There is currently no country in the world which can compare to Cuba in that sense. Its contributions are really amazing: the defense of Angola against South African aggression and Cuban doctors who are rendering their service in remote areas and taking the Cuban Revolution’s gains to others in places where few people would work. The gains that Cuba has achieved in education and public health are now helping to alleviate the suffering of other peoples. I’ve been able to take a first hand look at those contributions through personal contact, the warmth and enthusiasm of a wonderful people.”

Following such a jam-packed morning, Chomsky – the man who is said to share his opinions with thousands of people during his presentations – looks tired. However, before leaving, the most renowned critic of the US government, still had strength to answer a bunch of questions about the anti-globalization movement for a documentary produced by the center.

(English language version: Damián Donéstevez).