The delirious way in which we talk

What we consider dialogue was left behind in that imaginary ring where communication takes place. We waste what we want to say because of the way we say it. Let us hope that in time –not only with time!- we will be able to communicate.

Reynaldo González

digital@juventudrebelde.cu

May 4, 2013 19:54:47 CDT

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

|

||||

Sometimes I wonder if we Cubans

speak correctly, if we are really communicative –not “communicators”

because that is a professional matter for those who can do it- and if

our ideas are understood. I am concerned about the present popular

language of the majority of Cubans and, frankly, I find it sloppy

without concern for the accuracy of what is said, excessively full of

incomplete ideas and words whose meanings do not really correspond to

what is meant, too dependent on gestures to the extent that conversation

may seem a pantomime; all these without considering pronunciation,

because it would send us straight to the clinic of the diction

specialist. I will take up three issues: what we say, how we say it,

and the way in which we say it.

If I focus on the writing – and speech– in fashion, I should include

here some praise of Cuban popular speech, how much we have progressed,

achievements, victories and many etceteras. Something like striking

rocks to get sparks when what we mean is matches. And explain –covering

my back– that the following remarks refer to those of us who deserve

them, excluding the respectable and massive rest of the population.

These are habits of speech –and writing– that rarify conversation, make

it longer, and turn everything into “dissertations” (as disliked as that

is). I should make my point:

We don’t always understand what we say to each other, maybe because it

is uttered as a rebuff. For this we can blame shyness, a condition that

imposes an inexplicable hurry on the speaker. But, are there so many shy

people? To this speed we add bad pronunciation, mistakes in sound

articulation like flying over vowels and consonants to end quickly as if

we had to rush to an imaginary appointment. Thus, the listener rarely

gets something and we waste what we say.

The gestures on which we deposit most of our communication, are not

really allies, but opponents (and we love them so). They involve face

and hands –in some speakers also arms and shoulders and waist. It would

seem that gestures are substituted for words because we give them

content amplification value. Since each speaker has their own system of

gestures without a prescriptive “spelling” these are not completely

explicit. Gestures substitute for words and phrases; they steal their

meaning and leave behind a somewhat betrayed communication. This is the

risk of how we say it.

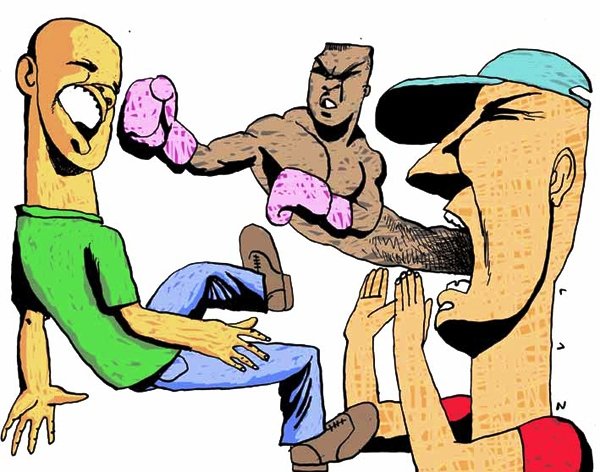

In the environment, because dialogue requires a context, the matter of

–in my view precarious– communication gets more complicated. Together

with our excessive gestures is the problem of tone. Our speech has

become expansive with too many decibels. High sounding voice is almost a

shout –covert or explicit– an imposition. If the interlocutor does the

same, the dialogue turns into a dispute. In a dispute there is no

dialogue, none of the “contenders” persuades the other of their

arguments. This is hitting and hitting back; avoiding the opponent's jab

until finding a weak side and striking there. To a voice that aims at

predominating we add the gestures –increasingly marked, becomes

overwhelming. Haven’t you heard a word that is now in fashion:

acaballar? [from: riding a horse].We don’t talk, we nos

acaballamos [ride on each other]. We do not coincide with or

persuade each other. What we consider dialogue has been left behind in

that imaginary ring where communication takes place. We waste what we

want to say because of the way in which we say it.

I heard a “popular” way to describe a fist fight:

«Oye, el tipo llegó, le dijo lo que le dijo, le bajó lo que le bajó, le

puso lo que le puso y lo dejó como lo dejó».

[“Listen, the guy got there, told him what he had to say, downed

him what he had to down, and left him as he was”]. This deserves a

reply: “What I liked best is the way you explained it.”

Are we already resigned to the theft of “the word”, that is, to the

acaballante version for taking part in conversations? This is

something we suffer even in allegedly educated milieus. When this is

done by a female doctor, for example, we feel like telling her in

popular language: «No seas tan imperfecta, chica». [“Dont’ be so

imperfect, girl”]. Who can tell whether two persons talking like that

understand each other, or think? And if this happens in a group?

More than a conversation it would be a rap jam. And if we need to learn

a glossary of implicits to make sense of the issue? And if they are

telling us a story and in the most interesting moment they cut the

ending with the classic: que pa’qué [and go figure]?

Let us hope that in time –not only with time!– we will be able to

communicate. We would be taking care of what we say, how we say it, and

the way in which we say it.

*Narrator and essayist.

Member of the Cuban Academy of Language.

La manera delirante en que hablamos Lo que creemos diálogo quedó sobre ese ring imaginario donde transcurre la llamada comunicación. Desaprovechamos cuanto queremos decir por la manera en que lo decimos. Esperemos que con el tiempo —¡no solo con el tiempo!— podamos comunicarnos Reynaldo González digital@juventudrebelde.cu 4 de Mayo del 2013 19:54:47 CDT

A veces me pregunto si los

cubanos hablamos con corrección, si somos verdaderamente

comunicativos —no «comunicadores», que ya es asunto de

profesionales, quienes puedan serlo— y si nuestras ideas son

comprendidas. Me ha preocupado el lenguaje actual y mayoritario

de los cubanos y, sinceramente, lo hallo atropellado, sin

preocupación por la exactitud de lo dicho, cargado de ideas

sobreentendidas, sin corresponder al significado cierto de las

palabras, demasiado apegado o dependiente de la gestualidad, que

convierte la conversación en una pantomima. Sin observar ahora

la pronunciación, que nos mandaría de cabeza a la consulta del

logopeda, escojo tres puntos: lo que decimos, cómo lo

decimos y la manera en que lo decimos. |

|