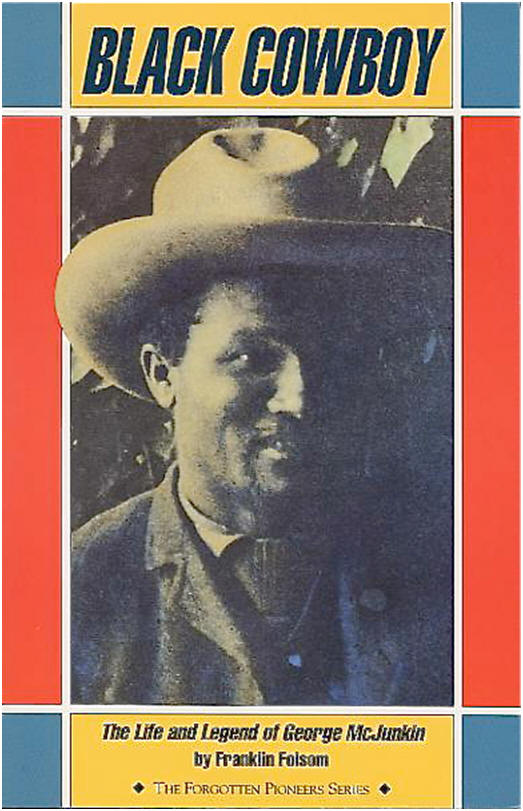

Black Cowboy and Pioneer of Anthropology

by Clifford D. Conner

George McJunkin in 1908

How many thousands of years ago did humans first cross from Asia to North America? The history of this scientific controversy is full of conflict between professional anthropologists and amateur bone-hunters. One of the most important of the amateurs' contributions was made shortly after the start of the 20th century. The hero of the story is a Black cowboy named George McJunkin, and the villain is Ales Hrdlicka, who was curator of the Smithsonian Institution's Division of Physical Anthropology. Hrdlicka ruled over the field of anthropology with an iron fist. His arrogance and intolerance of ideas that challenged his own made him a stereotype of a haughty overlord of science.

The establishment dogma that Hrdlicka defended to his death was that humans could not have arrived in the Americas more than three or four thousand years ago at the most. Hrdlicka had the power to destroy the careers of any anthropologists who dared to challenge that dogma, so dissent was effectively stifled within the profession. And dissent from outside the profession, from amateurs, was dismissed as the useless rantings of charlatans and crackpots.

George McJunkin was born into slavery in Texas in 1851. At age 14 he was freed by the Civil War and moved west to find work. He had never been to school and was completely illiterate, but he had a thirst for knowledge, so several years later when he found work on a ranch and the ranchers' sons offered to teach him to read and write, he eagerly accepted the opportunity, and once he could read there was no stopping him. He read everything he could get his hands on and developed a particular interest in all scientific subjects.

By 1908 he had worked his way up to being the foreman of a ranch-the Crowfoot Ranch near Folsom, New Mexico. In September of that year a flash flood destroyed a fence on the ranch, so McJunkin rode out to inspect the damage. He discovered that the flood had torn a ten-foot gully into the landscape, and he noticed some big bones sticking out at the bottom of the gully. McJunkin's self-education had prepared him to recognize that the bones were of some sort of bison, and to realize that they were too large to be from any living species, so he knew he'd made an important find.

He wrote letters to other amateur bone-hunters about his discovery, but he couldn't find any who were interested enough to make the thirty-mile, two-day ride on horseback that it would have taken to see them. McJunkin died 14 years later, in 1922, and in all that time nobody had ever come to see the bones he'd found.

However, two of the men he had contacted, a blacksmith named Carl Schwachheim and a banker named Fred Howarth, had not forgotten about what McJunkin had written to them. When Howarth bought an automobile, McJunkin's bone pit was then only an afternoon's drive away, and so they went to see it. Unfortunately, the timing was such that their first visit to see the bones was four months after McJunkin's death.

But they immediately recognized the importance of the discovery and began to try to bring it to the attention of the scientific community. Four years later, in 1926, they succeeded in interesting Jesse D. Figgins, the director of the Colorado Museum of Natural History. Figgins confirmed that the bones were those of an extinct Pleistocene bison, and so McJunkin's bone pit became the focus of systematic excavation. The following year, 1927, Schwachheim was digging there and made a truly momentous discovery. He found a Native American spear point, and it was embedded between the ribs of one of the extinct bisons. This was irrefutable evidence that human beings had been in the Americas for at least ten thousand years.

But irrefutable or not, it didn't matter to Ales Hrdlicka. He did everything in his power to discredit Figgins and the findings at Folsom, and went to his grave many years later continuing to insist that Native Americans could not have arrived in the Americas more than four thousand years ago. And unfortunately for science, he did have the power to prevent the Folsom findings from being accepted for many years. But more and more findings eventually overwhelmed the old orthodoxy. McJunkin's discovery had led to a scientific revolution, and to the creation of a new scientific paradigm that pushed the entrance of humans into the Americas back by six or seven thousand years.

It took almost fifty years after McJunkin's death for his role in this matter to come to light. Schwachheim and Howarth received some credit for the Folsom discovery, but McJunkin remained totally ignored until the 1960s when George Agogino, an archeologist at Eastern New Mexico University, heard an oral account of the story and was able to document it and publish it for the first time.

CLIFFORD D. CONNER is the author of A People's History of Science (Nation Books, 2005). A Cuban edition, Historia Popular de la Ciencia, was published in 2010 by Editorial Científico-Técnica.