Havana, Friday

January 18, 2013. Year 17 /

Issue 18

The

keys to conflict in Mali

Claudia Fonseca Sosa

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

The political crisis

in Mali caused by the coup d’état in March 2012 can be considered the

most serious one since 1960, the year of this African nation’s

independence from France, the very colonial power that acting president

Diouncounda Traoré has now turned to for help against the advancing

anti-government armed groups who have taken control of the northern

region.

French

soldiers in Mali.

French

soldiers in Mali.

On Monday, the UN

Security Council –of which France is a permanent member– gave the French

army the go-ahead to intervene in the conflict, together with forces of

the Economic Community of West African States, in order to assist the

weak Malian army.

However, the roar of cannons has been heard since January 11, when the

government decreed a national state of emergency. Vague reports have it

that thousands of people have fled to neighboring countries like

Algeria, Mauritania and Senegal, creating a situation likely to unleash

a humanitarian crisis in northern Africa.

SCENARIOS

Diplomatic sources agree that several armed forces with different goals

are involved in the conflict. For instance, the Islamist group Ansar

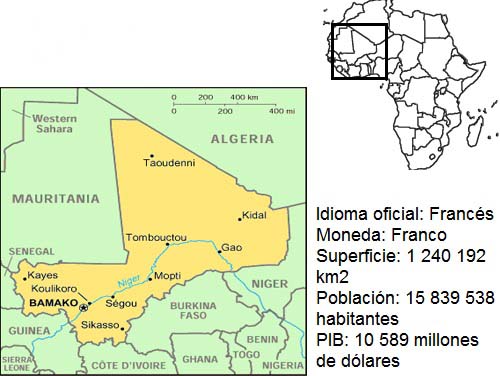

Dine is holding Mali’s major northern cities: Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao,

where they intend to impose strict Sharia law to a Muslim majority in a

nation constitutionally defined as a secular state with freedom of

worship.

|

|

In turn, Tuareg fighters

with the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) seek

recognition of what they call the Independent State of Azawad –made up

of the above three areas plus the town of Mopti– a region amounting to

almost half of the national territory which the Government lost since

early 2012.

Other smaller groups like MUJAO (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West

Africa) also take part in the rebellion, whereas foreign jihadist

insurgents are said to be setting up training grounds in areas under

rebel control.

It’s worth mentioning too that the MNLA rank-and-file brims with Malian

Tuaregs who have been involved in other regional conflicts and who have

returned to Mali, highly trained and armed to the teeth. According to

French intelligence sources, these fighters are equipped most of all

with infantry weaponry they might have bought from local arms dealers,

which would entail an upward trend in this illegal activity should the

conflict escalate.

After President Amadou Toumani Touré was ousted in a coup led by

soldiers dissatisfied with the boom of insurgency across Mali, power

passed to then-National Assembly Speaker Diouncounda Traoré. Yet, he

couldn’t stifle the rebellion either.

As a result of the instability following the coup –headed by

U.S.-trained Captain Amadou Sanogo– the radical Islamists found it

easier to get hold of the territories currently under their thumb.

WHAT IS FRANCE TRYING TO ACHIEVE?

Even if it was the Malian government itself which requested the presence

of its former colonial power in the conflict, political pundits don’t

rule out the possibility that France will seize on the so-called “war on

terrorism” to get a whole new slice of this cake, so rich in

hydrocarbons and mineral resources such as gold and the controversial

uranium. Could this be President François Hollande’s secret plan? Or is

his unexpected move nothing but a ruse to draw the media’s attention

away from his falling popularity and his unfulfilled electoral promises

in mid-crisis Europe?

Opponents of the intervention, including the French ex-presidential

candidate and Left Party co-president Jean-Luc Mélenchon, notice that

the UN Resolution on Mali stipulated a mission headed by African

countries, not France, which is really calling the shots now.

Pierre Laurent, national secretary of the Communist Party of France,

says that war is not the solution. He questions his country’s role

therein and deplores that the decision to intervene in Mali was made

without the consent of, or even a debate in, the French Parliament.

Nor should it be overlooked that France has a history of interference in

its old dominions –Gabon, Central African Republic, Ivory Coast and the

Republic of Congo– in times of uprisings, coups d’état and political

turmoil. In fact, to quote the British analyst Tim Whewell, France “has

never left the region entirely”.

Meanwhile, both the United States and NATO stand behind President

Hollande’s initiative and have offered logistical help (drones and

intelligence), albeit neither has committed to providing their soldiers.

In contrast, the European Union has already pledged to make troops

available.

A gloomy picture is again hanging over the continent that is both the

richest in natural resources and the hardest hit by human selfishness

and greed. Is Mali set to become the next Afghanistan?

La Habana, viernes 18 de enero de 2013. Año 17 / Número 18

Las claves del conflicto en Mali

CLAUDIA FONSECA SOSA

La crisis política que vive Mali por estos días, tras el golpe de Estado de marzo del 2012, puede considerarse la más grave desde que este país africano logró independizarse de Francia en 1960. La misma potencia colonial a la cual acude ahora el presidente interino Dioncounda Traoré en busca de ayuda para frenar el avance de los grupos armados antigubernamentales que ocupan el norte del país.

:

SOLDADOS FRANCES EN MALI.

:

SOLDADOS FRANCES EN MALI.El Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU —del cual Francia es un miembro permanente— aprobó el lunes la intervención militar gala y la participación en ella de las fuerzas de la Comunidad Económica de los Estados de África Occidental, en apoyo al débil ejército maliense.

Pero en el campo de batalla resonaban los cañones desde el 11 de enero, cuando el Ejecutivo de Mali decretó el estado de emergencia nacional. De acuerdo con estadísticas difusas, cientos de miles de personas se han visto obligadas a emigrar hacia países vecinos como Argelia, Mauritana, Senegal... ; lo que pudiera desencadenar una crisis humanitaria en el norte de África.

ESCENARIOS

Fuentes diplomáticas coinciden en que el conflicto involucra a varios grupos armados con diferentes objetivos. Por un lado están los islamistas de Ansar Dine, quienes controlan las ciudades norteñas más importantes de mali: Tombuctú, Kidal y Gao. Ellos quieren imponer la Ley Sharia en una nación de mayoría musulmana pero definida constitucionalmente como Estado laico con libertad de expresión religiosa.

|

|

Los taureg del Movimiento Nacional de

Liberación del Azawad (MNLA) buscan, por su parte, el reconocimiento de

su autodenominado Estado Independiente del Azawad, comprendido por las

tres localidades mencionadas antes, más una parte de Mopti. Una zona

sobre la cual el Gobierno no tiene control desde principios del 2012 y

que equivale a casi la mitad del territorio nacional.

Otros colectivos más pequeños como el Movimiento para la Unidad y la

Jihad en África Occidental (Mujao) también participan en la rebelión.

Mientras, informaciones no corroboradas señalan que insurgentes

yihadistas extranjeros están estableciendo campos de entrenamiento en

las zonas que están en manos de los opositores.

Es necesario destacar, además, que en las filas del MNLA hay taureg

malienses que estuvieron involucrados en otros conflictos regionales y

regresaron a Mali entrenados y con abundante armamento. La Inteligencia

francesa afirma que estos combatientes poseen, sobre todo, armas de

infantería que pudieron haber sido compradas a traficantes locales, por

lo que de extenderse el conflicto esta actividad ilegal tendería a

incrementarse.

Tras el golpe de Estado al presidente Amadou Toumani Touré, perpetrado

por fuerzas militares descontentas con el auge de los movimientos

insurgentes en el país, el entonces presidente de la Asamblea Nacional,

Dioncounda Traoré, asumió el liderazgo de Mali. Sin embargo, este

tampoco pudo controlar la situación.

La inestabilidad originada luego de la acción golpista encabezada por el

capitán Amadou Sanogo —quien recibió entrenamiento militar en Estados

Unidos— facilitó la toma de los territorios ocupados actualmente por los

islamistas radicales.

¿QUÉ BUSCA FRANCIA?

Aun cuando fue el propio Gobierno maliense el que solicitó la presencia

de su expotencia colonial en el conflicto, analistas políticos no

descartan la posibilidad de que Francia aproveche la llamada "guerra

contra el terrorismo" para hacerse de un nuevo pedazo de pastel muy rico

en hidrocarburos y recursos minerales como el oro y el controvertido

uranio. ¿Será este el motivo oculto del presidente Francois Hollande o

su imprevista misión no es más que un mecanismo para desviar la atención

mediática de su pérdida de popularidad y sus incumplidas promesas

electorales, en medio de la crisis europea?

Voces contrarias a la intervención, como la del copresidente del Partido

de Izquierda y excandidato presidencial francés, Jean-Luc Mélenchon,

observan que la resolución de la ONU sobre Mali estipulaba una misión

encabezada por países del continente africano y no por Francia, como en

la práctica está sucediendo.

El secretario nacional del Partido Comunista Francés, Pierre Laurent,

quien asegura que con la guerra no se solucionará nada, cuestiona

asimismo la actuación de su país y lamenta que la decisión de intervenir

en Mali se tomase sin autorización ni debate en el Parlamento.

No se puede olvidar tampoco que Francia tiene un amplio historial

injerencista en sus antiguos dominios coloniales en momentos de

revueltas, golpes de Estado e inestabilidad política. Tales fueron los

casos de Gabón, la República Centroafricana, Costa de Marfil y la

República del Congo. De hecho, el país europeo "nunca ha dejado la

región del todo", apunta el analista británico Tim Whewell.

En tanto, Estados Unidos y la Organización del Tratado del Atlántico

Norte dieron el visto bueno a la iniciativa del presidente Hollande y le

ofrecieron apoyo logístico (drones e inteligencia) para sus maniobras,

aunque todavía no se han decidido a enviar soldados. En cambio, la Unión

Europea ya anunció su envío de tropas para mediados de febrero.

Un oscuro escenario se cierne nuevamente sobre el continente más rico en

recursos naturales y, a la vez, el más maltratado por el egoísmo y la

ambición humana. ¿Será Mali el próximo Afganistán?

http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2013/01/18/interna/artic05.html