A New Cuban

Detective Novel

A

CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

In Cuba, detective novels are considered to be more than entertainment,

and the most significant works are not –like in other countries or for

other writers– simple “airport literature”. There are important writers

of the genre in the country, among them Daniel Chavarría and Leonardo

Padura, both winners of the National Literary Award (2010 and 2012,

respectively) a once in a lifetime honor. They are also winners of many

literary prizes in Cuba, Europe and the US. Their novels, most of them

of the “noir” genre and based on social reality, have gained them

prestige both in Cuba and in other countries. Chavarría and Padura are

probably Cuba’s best known living authors and most published abroad.

Now a new Cuban detective novel has been calling attention even before

its publication. Un toque de melancolía (A Touch of Melancholy),

by novelist and journalist Germán Piniella, will be published shortly by

Ediciones Unión [Unión Publishers] and possibly launched at the

coming Havana International Book Fair in February. Two literary

magazines are considering publishing excerpts of the novel.

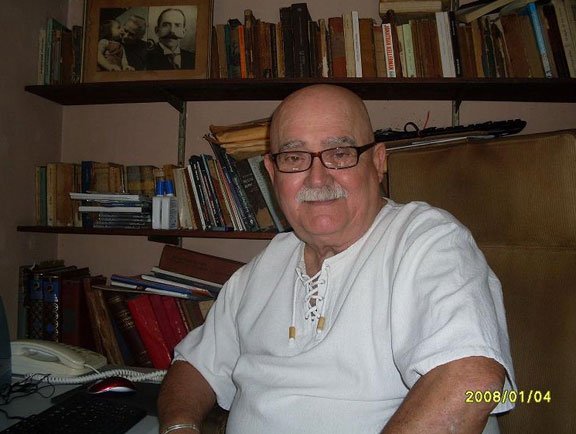

Germán Piniella Sardiñas (Havana, 1935) is a writer, journalist,

translator and music critic. His short stories and commentaries have

appeared in prestigious Cuban magazines such as Casa de las Américas,

La Gaceta, Bohemia, El Caimán Barbudo, La Jiribilla and others,

as well as in publications abroad. He has also written liner notes for

most of Cuba’s recording labels. He has published the short story volume

Otra vez al camino (Editorial Pluma en Ristre, 1971), a finalist

on the David Prize in 1969; Punto de partida (Pluma en Ristre,

1970), an anthology of young fiction writers and poets, together with

Raúl Rivero; and the book on culinary culture Comiendo con Doña Lita

(Arte y Literatura, 2010), in collaboration with his wife,

psychologist and food critic Amelia Rodríguez. Several of his short

stories have appeared in anthologies in Cuba and a number of countries.

He currently works as Associate Editor of Progreso Semanal/Weekly,

a bilingual Internet magazine (www.progreso-semanal.com).

Evidence of the interest this novel has generated are the following

comments by well known fiction writers Eduardo Heras León and Hugo Luis

Sánchez, part of the assessment that both writers made for Ediciones

Unión and that will appear as commentaries in the edition.

According to Heras León, the book has “(…) a most interesting plot that

follows exactly the rules of the genre: intrigue, mystery, crimes and

plausible solution, which together with an intelligent and far from

schematic design of the characters and a language perfectly adjusted to

the contents turn the novel into a noteworthy example of the author’s

high degree of professionalism and creativity.”

For his part, Sánchez believes that “A Touch of Melancholy is

surely among the best Cuban detective novels of all times. Its greatest

merit lies in intelligence and thus in the respect for the reader’s

intelligence. The solutions are unexpected, ingenious and believable.”

Why has an unpublished novel stirred up such expectations? Will a work

written by an author that abandoned fiction writing for many years live

up to these expectations? In search of answers we decided to interview

Piniella.

CubaNews: In the 1970s you were known as a science-fiction writer,

and as such you appeared in anthologies both in Cuba and abroad. Then

you stopped writing fiction for many years, although kept active in

journalism and music critiques. Why have you returned to fiction; this

time switching genres?

Germán Piniella: I stopped writing fiction for personal reasons that

I rather not comment on right now. Perhaps I’ll write about it someday.

Now I come back to fiction for reasons that are also personal and

because of the insistence of some friends and colleagues. In the matter

of switching genres, I don’t see any reason not to. Dashiell Hammet and

Raymond Chandler raised the detective or mystery novel to the rank of

serious literature because it allowed the authors to describe certain

facts of society, with its glows and shadows, charms and miseries –for

experts, the stuff that literature is made of. On the other hand, there

are great writers that have trod on different paths regularly. I think

of the Argentinean Jorge Luis Borges and the Cuban Alejo Carpentier,

just to mention two classics. In recent years, in Cuba we have the

example of Leonardo Padura, an excellent writer of detective novels, but

also the author of works such as La novela de mi vida (The

Novel of My Life) y El hombre que amaba a los perros (The Man Who

Loved Dogs), which have achieved for Padura as much or more

recognition from readers and critics than his character Detective Mario

Conde. Daniel Chavarría is famous for his police and espionage novels,

but also because his short stories are no strangers to other genres and

for his autobiography (which in spite of its genre is read like an

adventure, –as his life has been). At present he is working on a project

that has nothing to do with detective stories –the biography of Raúl

Sendic, leader of the Uruguayan urban guerrilla Tupamaros in the 70s and

80s. I don’t use these arguments to compare myself with the afore

mentioned writers, of course, but to show that relevant writers refuse

to accept that it is mandatory to stick to a single genre or subject

matter. Therefore, I have that right too.

CubaNews: When you decided to return to literature, your comeback was

not with a traditionally-written short story or with a linear novel.

According to some who have read it, A Touch of Melancholy, is a

massive work with a complex structure, several languages and many

characters.

GP: It is really long-winded, and perhaps I overdid it when I wrote

400 pages. But the fault is not entirely mine. The story I tell is also

responsible because it has a life of its own. About five years ago I was

writing another novel that at present I am halfway through, under the

provisional title of Blues para Quijano [Blues for Quijano]

(it will be much shorter, I promise), when Daniel Chavarría telephoned

me one afternoon. I not only admire him, but we are also joined by a

long friendship. What’s more, Chavarría and I share great friends, a

passion for good detective novels, and a healthy enthusiasm for wine.

The call was for proposing a double authorship in a short novel that his

German editor had asked him to write. Time was running out and he had

other commitments that would not allow him to be on schedule, were he to

write all by himself.

I accepted, of course. After so many years of silence and since I wanted

to make a comeback -a fact that almost made me a senile candidate for a

beginners prize- to be in the international market hand-in-hand with

Daniel was a great opportunity. His editor had two conditions: the main

character had to be German and there must be a presence of Cuban cuisine

in the story. Daniel asked me to send him an outline of a plot so that

we could later discuss it and soon after start writing. A couple of days

later I submitted to him a sketch of the story. But I didn’t wait for

Chavarría’s comments. Instead I began writing the story of a German

couple who arrived in Cuba: he to do business and she as a housewife.

For different reasons -of which neither Daniel nor I were responsible-

the project fell through. I went back to my interrupted novel. But my

wife Amelia, to whom I owe so much, insisted that I should go back to

the plot that I had sent Chavarría and begun to draft. She thought it

was promising. It was then that the nature of the story changed, but I

kept the two original conditions, which I thought were valid. As it had

to be more solid in order to be a full-length novel, the plot went back

to 16th century Germany and covered several countries and time periods

up to its climax in present day Cuba. Chavarría encouraged me with his

usual epithets. Then…isn’t it understandable that a period of four

centuries and a number of countries needed so many pages?

CubaNews: In spite of its length, the existing opinion is that the

reading is not cumbersome, but flows easily. Did you choose to be

entertaining?

GP: Yes, but not in the manner some people think this is done and

consciously try to “lower the level”, use an “easy” language or a

“simple” structure for achieving communication. I believe that above all

a writer should respect readers. And of course, be totally honest with

himself.

CubaNews: Tell me about the subject matter of the novel.

GP: I wanted to write a story in which fictitious characters (and

some real ones who also appear) are motivated by love, aesthetic

pleasure and/or ambition. Some struggle to maintain their dignity and

survive, others are immersed in a game of deceit, fraud and swindle.

And all pay a price in an atmosphere of cultural clash, conspiracy, sex

and treason. It’s not a new situation, but one to which human beings

return time and again. The difference lies in the anecdote, in how it

evolves according to the idea. You have to find the language that is

implicit in the subject matter and the plot, in the same manner that

Michelangelo said that a sculpture is hidden in the stone. You just have

to carve away the surplus. That’s the reason for the various languages,

depending on the period, the country where the plot is evolving and the

nature of the character. But there is no intention of embarking on an

“adventure of language”. I don’t believe in a pompous literature with

long paragraphs filled with transcendent words and profound meditations,

but where nothing happens. I am certain that if a word is not absolutely

indispensable, it falls in the category of surplus. For me, the crux of

the matter is to narrate what is happening through the acts and words of

the characters. Every single work of literature that I have read and I

considered great, regardless when it was written, has been a source of

emotion, not those that overwhelm and smother me with “important”

adjectives and adverbs.

CubaNews: So this is not a thesis novel?

GP: Every work of creation, even a pop song, is an aesthetic

proposal and also an ethical one, even if the author is conscious of it

or not. That is also the case of A Touch of Melancholy, but at

the level of a thriller, an adventure that evolves discovering new

conflicts that on occasion seem unsolvable, until you see the light. Oh!

And never leaving loose ends.

CubaNews: Heras León writes about a “very interesting plot”. Can you

summarize it?

GP: The novel is a long journey of over four hundred years, from

1527 to present day Cuba. It is about the search for a mythical

engraving by master painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer. The search is

carried out by the Consortium, a German semi-clandestine organization

dedicated to secret trafficking in works of art, and also by a lonesome

rival. The investigation takes the reader through the Dutch War of

Independence, a pilgrimage on the Camino de Santiago [Road

to Santiago de Compostela], Paris in the 1930s, the beginning of the

Spanish Republic, Nuremberg today, Havana in 1959, and present-day Cuba.

The thread is the engraving Melancholia II. (Dürer made

Melancholia I in 1528, which means that he had the intention of

making at least one more.) At the end of the book there is an annex (“Regla

Fresneda’s recipes”) with the dishes that one of the characters makes

and that are an essential part of the plot.

CubaNews: Will we witness the launching of A Touch of Melancholy

at the coming Havana International Book Fair?

GP: The novel has had a long editorial process of almost three

years. I wish it could be present at the Fair, but that’s a puzzle that

no detective can solve.

Havana, January 2013

Nueva

novela policiaca cubana

En Cuba, la novela policiaca goza de prestigio más allá del

entretenimiento, ya que sus obras más significativas no son –como en

otras partes o para algunos escritores– mera lectura de aeropuerto. Hay

cultores importantes en el país, entre otros Daniel Chavarría y Leonardo

Padura, ambos galardonados con el Premio Nacional de Literatura (2010 y

2012 respectivamente) y ganadores de innumerables lauros literarios en

Cuba, Europa y Estados Unidos. Sus obras, la gran mayoría del tema

policiaco y ancladas en la realidad social, han dado prestigio a sus

autores, tanto en el país como el extranjero. Ellos posiblemente sean

los escritores en ejercicio más conocidos y publicados fuera de Cuba.

Ahora, una nueva novela policiaca cubana está causando comentarios aún

antes de salir a la luz. Me refiero a Un toque de melancolía,

del escritor y periodista Germán Piniella, la cual saldrá publicada en

breve por Ediciones Unión y que es posible que esté a la venta en la

próxima Feria Internacional del Libro de La Habana. Dos revistas

literarias, una de reciente creación y otra de las más antiguas del

país, están considerando publicar fragmentos de Un toque…

Germán Piniella Sardiñas (La Habana, 1935) es narrador, periodista,

traductor literario y crítico musical. Cuentos y comentarios suyos han

aparecido en la revista Casa de las Américas, La Gaceta,

Bohemia, El Caimán Barbudo, La Jiribilla y otras, así como en

publicaciones extranjeras. También ha escrito notas de carátulas de

discos para todas las disqueras cubanas. Ha publicado el libro de

cuentos Otra vez al camino (Editorial Pluma en Ristre, 1971),

finalista del Premio David en 1969; Punto de partida (Pluma en

Ristre, 1970), antología de jóvenes narradores y poetas, conjuntamente

con Raúl Rivero; y el libro de cultura culinaria Comiendo con Doña

Lita (Arte y Literatura, 2010), en colaboración con su esposa, la

psicóloga Amelia Rodríguez. Varios de sus cuentos han sido antologados

en Cuba y en varios países. Actualmente se desempeña como editor

asociado de Progreso Semanal, revista bilingüe en Internet (www.progreso-semanal.com).

Muestra de la atención que ha suscitado esta novela son las siguientes

valoraciones de los conocidos narradores Eduardo Heras León y Hugo Luis

Sánchez, parte de la evaluación que ambos escritores hicieron para

Ediciones Unión y que en la publicación se incluirán a modo de

comentarios.

Según Heras León, la obra tiene “(…) un interesantísimo argumento que

cumple a plenitud con los presupuestos de una novela del género:

intriga, misterio, crímenes y solución verosímil, lo que unido a un

inteligente y nada esquemático trazado de los personajes, y un lenguaje

en perfecta adecuación con los contenidos narrados, la convierten en una

notable muestra del alto grado de profesionalismo y creatividad del

autor.”

Por su parte, Sánchez considera que “Un toque de melancolía (…)

con seguridad se encuentra entre las mejores novelas policíacas que se

han escrito en Cuba hasta el presente. Su mérito mayor radica en la

inteligencia y, por ende, en el respeto a la inteligencia del lector.

Las soluciones son inesperadas, ingeniosas y creíbles.”

¿Por qué ha suscitado tal interés una novela aún inédita? ¿Estará a la

altura de las expectativas una obra escrita por un autor que mantuvo

años de silencio narrativo? En busca de respuestas quisimos entrevistar

al escritor.

CubaNews: En la década de 1970 usted era conocido como autor de

ciencia ficción, y como tal ha sido antologado en Cuba y el extranjero.

Luego vinieron para usted años de silencio en el campo de la narrativa,

aunque no en el periodismo y la crítica musical. ¿Por qué vuelve ahora a

la ficción y además cambia de género?

Germán Piniella: Dejé de escribir ficción por razones personales que

no vienen al caso comentar aquí, pero sobre las cuales quizás escriba

algún día. Ahora vuelvo a la narrativa por razones también personales y

por insistencia de algunos amigos y colegas. En cuanto a cambiar para el

policial, no veo por qué no hacerlo. Desde Dashiell Hammet y Raymond

Chandler, la literatura policiaca adquirió rango de literatura seria

porque se convirtió en marco para retratar hechos determinados de la

sociedad, con sus luces y sombras, aciertos y miserias –para muchos

conocedores, la sustancia de que está hecha la gran literatura. Por otra

parte, hay excelentes escritores que han transitado con regularidad por

distintos temas. Pienso en el argentino Jorge Luis Borges y en el cubano

Alejo Carpentier, para solo mencionar dos clásicos. En años recientes,

en Cuba tenemos el ejemplo de Leonardo Padura, excelente escritor de

novelas policiacas, pero autor también de obras como La novela de mi

vida y El hombre que amaba a los perros, que le han dado

tanto o más reconocimiento de parte de lectores y críticos que su

personaje del detective Mario Conde. Daniel Chavarría es bien conocido

por sus novelas policiacas y de espionaje, pero también por cuentos

ajenos al tema y por su autobiografía (que se lee, no obstante el

género, como un libro de aventuras –como ha sido su vida). Ahora está

enfrascado en un proyecto también ajeno al tema policiaco, la biografía

de Raúl Sendic, líder de los Tupamaros, la guerrilla urbana uruguaya en

las décadas de 1970 y 1980. No uso este argumento para situarme al nivel

de los mencionados, por supuesto, sino para demostrar que escritores

relevantes desmienten el hecho de que sea obligatorio dedicarse a un

solo género o tema. Entonces yo, salvando distancias, también tengo

derecho.

CubaNews: Cuando decidió volver a la literatura, no comenzó

por un cuento al estilo tradicional o una novela lineal. Según algunos

que la han leído, Un toque… es una larga obra de estructura

compleja, varios lenguajes y muchos personajes.

GP: Es cierto lo de larga, ya que quizás se me haya ido la mano al

escribir casi cuatrocientas páginas. Pero la culpa no es exclusivamente

mía. También de la historia contada, que tiene vida propia. Hace unos

cinco años estaba escribiendo otra novela policiaca que actualmente

está a medio camino, con el título provisional de Blues para Quijano

(será más corta, lo prometo), cuando una tarde recibí una

llamada de Daniel Chavarría, a quien no solo admiro, sino con quien

también tengo una larga amistad. Daniel y yo compartimos además a

grandes amigos, la pasión por la buena literatura policiaca, un

desenfrenado fervor por conversaciones interminables y un sano

entusiasmo por el vino. La llamada de Daniel era para proponerme

escribir a cuatro manos una noveleta que él debía entregar a su editor

en Alemania. El tiempo era corto y otros compromisos le impedían tener

la obra en fecha si la hiciera solo.

Por supuesto que acepté. Después de años sin publicar y querer retornar

al ruedo, lo que casi me convertía en un senil candidato a un premio

para principiantes, salir al mercado internacional de la mano de Daniel

Chavarría era una oportunidad de lujo. Había dos condiciones de los

editores: un alemán como protagonista y la presencia de la cocina cubana

en la trama. Yo debía enviar a Daniel un esbozo de argumento para

después comenzar las discusiones conjuntas y la redacción subsiguiente.

Un par de días después le presenté mi propuesta, pero no esperé a que

Daniel me hiciera sus observaciones y comencé a escribir la historia de

un matrimonio alemán que llega a Cuba, él a hacer negocios y ella de ama

de casa.

Por diversas razones, ninguna achacable a Daniel o a mí, el proyecto no

cuajó. Yo me resigné y volví a mi novela interrumpida. Pero mi esposa

Amelia, a quien mucho debo, me insistió en que retomara el argumento que

había enviado a Daniel y que ya yo había comenzado a redactar. A ella le

pareció que prometía. Fue entonces que la historia cambió de carácter,

aunque mantuve las dos primeras condiciones de Daniel, que me parecieron

válidas. Como debía tener más cuerpo para ser novela, la historia se

remontó al siglo 16 en Alemania y pasó por otros países y épocas hasta

su desenlace en Cuba. Daniel me alentó con sus generosos epítetos de

siempre. Quizás se comprenda que dado el período de cuatro

siglos y varios países me hicieran falta tantas páginas.

CubaNews: Sin embargo, a pesar de su extensión, la opinión existente

es que no es una lectura farragosa, sino que fluye con facilidad. ¿Se

propuso que fuera amena?

GP: Sí, pero no de la manera que entienden algunos que a conciencia

se proponen “bajar el nivel”, utilizar un lenguaje “fácil” o una

estructura “simple” en aras de la comunicación. Creo que lo primero que

debe hacer un escritor es respetar al lector. Y claro, ser totalmente

honesto consigo mismo.

CubaNews: ¿Cuál es el tema de la novela?

GP: He querido hacer una historia en la que los personajes ficticios

(y algunos reales, que también aparecen) estén motivados por el amor, el

goce estético y/o la ambición. Unos tratan de mantener la dignidad y

sobrevivir, otros se dedican a un juego de engaño, fraude y estafa. Y

todos pagan un precio y quedan atrapados en una atmósfera de choque de

culturas, conspiración, sexo y traición. No es una cuestión nueva, sino

situaciones a las que pueden volver los seres humanos una y otra vez. La

diferencia estriba en la anécdota, en cómo se desarrolle en función de

la idea. Hay que encontrar el lenguaje que llevan implícito el tema y el

argumento, de la misma manera en que Miguel Ángel decía que una

escultura estaba escondida en la piedra. Solo es cuestión de buscarla y

quitar lo que sobra. Por eso hay multiplicidad de lenguajes, en

dependencia de la época, el país donde se desarrolla la trama y el

carácter de los personajes. Pero no hay pretensión de hacer “una

aventura del idioma”. No creo en la literatura pomposa de largos

párrafos con palabras trascendentes y profundas meditaciones, pero en la

que no sucede nada. Estoy seguro de que si una palabra no es

imprescindible, sobra. Para mí, el meollo del asunto está en narrar lo

que sucede por medio de los actos y las palabras de los personajes. Toda

la literatura que he leído y me ha parecido grande, independientemente

de cuándo ha sido escrita, es la que me provoca emociones, no la que me

apabulla a fuerza de adjetivos y adverbios imponentes.

CubaNews: ¿Puede decirse entonces que no es una novela de tesis?

GP: Toda obra de creación, hasta una canción pop, es una propuesta

no solo estética, sino ética. Aunque el autor no se lo proponga o no lo

haga de manera consciente. En el caso de Un toque de melancolía

lo es también, pero a nivel de thriller, es decir una aventura

que avanza descubriendo nuevos conflictos, que en varias ocasiones

parece que no van tener solución, hasta que al fin se ve la luz. ¡Ah! Y

en no dejar un solo cabo suelto.

CubaNews: Heras habla de “un interesantísimo argumento”. ¿Puede

resumirlo?

GP: La novela es un largo recorrido de más de cuatro siglos, desde

1527 hasta la Cuba actual. Trata de la búsqueda de un mítico grabado del

pintor y grabador alemán Alberto Durero. La pesquisa se hace por parte

del Consorcio, organización alemana semiclandestina dedicada al tráfico

secreto de obras de arte, y también por un rival suyo en solitario. La

indagación lleva al lector por la guerra de Flandes, el peregrinar en el

Camino de Santiago, el París de los años 30, el inicio de la República

Española, Núremberg hoy en día, La Habana de 1959 y la Cuba actual. El

hilo conductor es el grabado Melancolía II. (Durero realizó Melancolía I

en 1528, lo que evidencia su intención de hacer al menos uno más.) Al

final de la novela agrego un anexo (“Las recetas de Regla Fresneda”),

con los platos que elabora uno de los personajes principales y que son

parte esencial del argumento.

CubaNews: ¿Asistiremos en la próxima Feria Internacional del Libro de

La Habana al lanzamiento de Un toque de Melancolía?

GP: La novela ha sufrido un largo proceso editorial de casi tres

años. Ojalá pueda presentarse en la Feria, pero ese es un enigma que

ningún investigador policial puede desenredar.

La Habana, Enero 2013