Bohemia

October 3, 2005

Unusual?

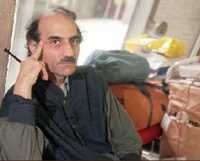

There

are underworlds within this world. Merhan Karimi Nasseri has been living in his

own for the last 17 years. His sunken eyes, dry and lifeless, his pale and harsh

face, and even his thick moustache, immediately reveal a lonely being trapped by

a series of circumstances who still wonders why he was treated with such hurtful

injustice.

There

are underworlds within this world. Merhan Karimi Nasseri has been living in his

own for the last 17 years. His sunken eyes, dry and lifeless, his pale and harsh

face, and even his thick moustache, immediately reveal a lonely being trapped by

a series of circumstances who still wonders why he was treated with such hurtful

injustice.

Given his situation and context, he looks surprisingly outgoing and pays careful attention to whoever comes to his ‘office’, which many do especially after a film based on his monumental tragedy was released in 2004. Nor is he prone to lose his composure and tolerance, considering that he suffers from serious alterations regarding his perception of reality.

Tom Hanks stars in Steven Spielberg’s next-to-last movie (The Terminal, shown on Cuban TV on a Sunday afternoon and rerun the following Saturday by popular demand), where he embodies this man who is neither named Víktor Navorski, nor is he a citizen –of course– of fictitious Krakozhia, although the rest of the story is pretty close to the real thing.

Born in Iran’s Kurdistan in 1942 to a British mother and an Anglo-Iranian father, Karimi had a professional education to be envied by most of his compatriots, namely a degree in Psychology attained in Tehran as well as Social Sciences studies in Britain’s Bradford University in Yorkshire, until he turned 35 in 1977 and returned to his home country.

It only seemed to be an annoying inconvenience for which there would finally be a solution. Besides, he was looking forward to returning to England to track his first-world origins, and had even thought of settling in London, so it is quite likely that he was pleased about that fluke of destiny.

Very soon was his fate upset and, even worse, his life twisted by his own yearnings as well as by events and circumstances – there goes the same word again. His government imposed an unappealable resolution on him: banishment. It happened that Karimi had eagerly joined popular demonstrations against shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi’s regime, and the leader decided to fly him anywhere, without any passport or documents.

Yet, the sort of romantic nimbus surrounding his forced exile began to drift away as soon as he arrived in the famous Big Ben’s venue, where the authorities flatly refused him his right to be granted asylum. And believe it or not, after that he kept traveling from city to city through half of Europe for four years without getting to put down roots in any of them.

A long journey

There was no shortage of arrangements until 1981, when he managed to have his status recognized and get asylum in Belgium by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in that nation. Nasseri kept jumping from Belgium to France and vice versa till 1988. He was in Paris when he finally made up his mind and made the visit he craved to his ancestors’ capital city, though to his bad luck someone at a Parisian train station robbed him of the briefcase where he kept his credentials.

No one knows how, but he managed to get to London’s Heathrow airport. However, he was sent unceremoniously back to Paris as soon as the authorities found out he had no identity papers. On a gloomy August day in 1988, he arrived at the City of Light’s Charles de Gaulle airport terminal No. 1 as a castaway on an island.

It would be just another stopover, he thought. He had to start dealing with paperwork all over again to get his documents, by that time in the hands of who knows what other illegal resident in Paris, Karimi was pondering as he toured the glass-covered and aerial halls or rode the huge airport’s escalators.

But what began looking like a true adventure proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. The perpetual illegal traveler, citizen of nowhere in the world, is quickly caught out by the French police and kept four months in detention for not having a passport, right until they concluded that he lacked the conditions to be deported to any country. At 46, the ‘world’s most famous stateless person’ – as he is referred to – faced nothing but neglect.

He was burning with outrage and paralyzed with enormous exhaustion, but nonetheless decided to take the bull by the horns and instead of licking his wounds, forced himself to raise his spirits and fight for survival, the strongest of all instincts. While he converts several chairs into a makeshift bed, a bunch of suitcases and boxes into a cupboard and bookcase, and tried to support himself in the madhouse that Terminal No. 1’s lounge really is, he gradually learns to endure time’s dictatorship.

A hard blow would come when he tried to get new documents as a refugee, since the Belgian authorities refused to send them by mail. It was not before 1995 that he was permitted to pick them up in person, and on two conditions: he was to stay there forever, and live under a social worker’s supervision, an involuntary exile of sorts that Nasseri – after seven years in airports and obvious symptoms of mental disorder – decided to reject.

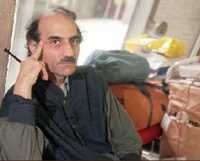

Thus, when in 1999 the French government gave him a residence permit and therefore a possibility to move around Europe, he said no once again. By then he no longer recognized himself in his native nationality nor under his own name. Everybody calls him Sir, Alfred, the la formula used – including the comma – in a letter addressed to him by British immigration officials.

As weeks, months, and years stretched on, the human race’s darkest flaws and brightest virtues had been disclosed by that singular and singularized child of indolence because, as efforts and legal arrangements continued their comings and goings, a warm network of solidarity was woven around him by the staff of various airlines and service personnel in Terminal No. 1’s Transit Lounge at Charles de Gaulle.

Such fraternal and humanitarian attitudes were the key to eclipsing the worst actions he was subjected to, and I say it without the slightest bit of exaggeration. “He’s so likable and nice to be with; you can tell he comes from a good family. The airport authorities have come to like him, that’s why they let him live here", remarks a saleswoman of the terminal’s pharmacy who lets Nasseri use her phone.

It is said, for instance, that both the airport’s chief doctor and the priest rank among his best friends. "He’s afraid of leaving the cocoon in which he has lived these years", states the former, who is also his personal physician. "His papers are in order and he’s got economic resources but he’s reluctant to leave, for he only exists through the airport."

There are many who pamper him by getting him food, clothes and even things to read, not to mention daily newspapers. Since he has preserved his dignity in spite of his certain – and logical – imbalance, he won’t have anyone treating or seeing him as a beggar; at most, as a person who survived being shipwrecked in this complex world. What’s more, some are surprised to know that even amid his metamorphosis, Karimi is always clean and shows very good taste in clothes.

Tom

Hanks plays Nasseri

To most of the 35 million travelers who pass by Charles de Gaulle airport every year, Sir Alfred is just another passenger awaiting his flight. He personally feels no particular appeal to such travelers, either: "I am not interested in people who come to this airport", he declares. However, he likes receiving letters and being interviewed, and even poses for the cameras.

Now, as he adapts to fame, he keeps a bankbook with the large sum of money Spielberg’s film producers paid him for the rights to tell his story. "I can buy whatever I want, but I worry about loosing it or being robbed. I eat better and can buy plane tickets, though my lifestyle has not changed." Furthermore, he nurtures the idea of traveling to the American continent, since he’s almost fed up with Europe. For the time being, he is writing a diary and a book about his own life.

Meanwhile, and for his own sake, everyone in the Terminal trusts that he will eventually get around to break his mental ties and leave the premises where he has resided for so long. He himself has admitted that staying in an airport for such a long time is not a normal thing to do, observing that "it’s quite boring."

Those who know none of these details point out that The Terminal is not credible, even if they acknowledge its genius as a fable and a comedy. Truth be told, in addition to a brilliantly-acted and -directed motion picture – I say it as a moviegoer and not as a film expert, which I am not – this is a based-on-facts story about the atrocity and abuse that a capitalist society’s basic institutions might commit, also one about racism, xenophobia and indolence, because it remains to be seen whether under equal circumstances – again this word– , a citizen of the wealthy North would ever be submitted to so big an infamy.

(October 28, 2005)

http://www.bohemia.cubaweb.cu/2005/oct/03/sumarios/especiales/insolito.html

¿Insólito?

La muerte en

vida de un viajante

Estos son el protagonista y los hechos reales

recreados

por Steven Spielberg en su película La Terminal

Por: MAGGIE MARÍN

inter@bohemia.co.cu

Dentro

de este mundo hay submundos. En el suyo propio vive, desde hace 17 años, Merhan

Karimi Nasseri. En los ojos hundidos, secos y desolados, en la cara pálida y

cruda, hasta en su espeso bigote se perciben de inmediato al ser solitario

atrapado por una cadena de circunstancias, y que aún hoy se pregunta por qué se

cometió con él tan lacerante injusticia.

Dentro

de este mundo hay submundos. En el suyo propio vive, desde hace 17 años, Merhan

Karimi Nasseri. En los ojos hundidos, secos y desolados, en la cara pálida y

cruda, hasta en su espeso bigote se perciben de inmediato al ser solitario

atrapado por una cadena de circunstancias, y que aún hoy se pregunta por qué se

cometió con él tan lacerante injusticia.

Contra cualquier pronóstico, dadas las circunstancias y el contexto, se muestra afable y atiende con esmero a los que se acercan a su "despacho"; y que no son pocos, particularmente luego del estreno en 2004 de la cinta inspirada en su monumental tragedia. Tampoco es proclive a perder la compostura, ni a la intolerancia, a pesar de que sufre graves alteraciones del sentido de la realidad.

Protagonizado por Tom Hanks en el penúltimo filme de Steven Spielberg (La Terminal, transmitido en Cuba una tarde dominical de agosto y repetido el sábado inmediato a solicitud de los televidentes) este hombre ni se llama Víktor Navorski, ni es ciudadano –claro está– de la ficticia Krakozhia, aunque por lo demás la historia cinematográfica se apega bastante a la verdad.

Nacido en el Kurdistán iraní en 1942, de madre británica y padre anglo-iraní, Karimi completó una formación profesional que provocaría la envidia de muchos de sus coterráneos, porque a una licenciatura en Sicología obtenida en Teherán sumó estudios de Ciencias Sociales en la muy británica Bradford University, de Yorkshire, hasta que en 1977 y con 35 años, regresó a su país natal.

|

|

|

En maletas y cajas guarda libros, recortes de prensa y una abundante correspondencia que le llega de todo el orbe |

Aquello no parecía más que un fastidioso problema al que finalmente podría hallarle alguna solución. Además, ansiaba regresar a Inglaterra para rastrear los orígenes de su estirpe primer mundista y hasta tenía pensado establecerse en Londres, así que es muy posible que se alegrase de esa carambola del destino.

No había transcurrido mucho tiempo, cuando anhelos, hechos y circunstancias –vuelve la palabreja– comenzaron a contrariar su destino, o aún peor, a torcerle la vida. Su gobierno adoptó con él una resolución inapelable: desterrarlo. Sucedió que Karimi se había sumado con sobrado entusiasmo a las protestas populares contra el régimen del sha Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, y este resolvió enviarlo por vía aérea a cualquier parte, sin pasaporte ni otros documentos.

Pero el cierto nimbo romántico que ceñía su destierro comenzó a esfumarse cuando, una vez llegado a la ciudad del célebre Big Ben, las autoridades le negaron olímpicamente el derecho de asilo. Y aunque usted no lo crea, a partir de entonces estuvo viajando de ciudad en ciudad por media Europa, durante cuatro años, sin conseguir asentarse en parte alguna.

El largo andar

Gestiones no faltaron, hasta conseguir en 1981 que el Alto Comisionado de la ONU para los Refugiados en Bélgica le reconociera tal status y le concediese asilo en esa nación. Hasta 1988 vivió Nasseri a caballo entre Bélgica y Francia. En París estaba cuando decidió concretar finalmente la tan ansiada visita a la capital de sus ancestros; con tan mala estrella, que en una estación de trenes parisina le robaron un maletín con las credenciales.

|

|

|

Se levanta a las 5:30 de la mañana y se asea en el baño de hombres antes de que lleguen los pasajeros. Luego lee, escribe, y observa. Cuando anochese se acomoda en butacas para dormir |

Nadie sabe cómo, logra no obstante llegar a Londres, por el aeropuerto de Heathrow. Pero las autoridades, apercibidas de que se trata de un indocumentado, lo despachan de regreso a París sin contemplaciones. Como un náufrago en tierra arriba a la terminal No. 1 del Aeropuerto Charles de Gaulle, de la ciudad luz, un melancólico día de agosto de 1988.

No sería más que otra escala, pensaba. Tenía que reiniciar las diligencias en procura de sus documentos, que a esas alturas estarían en poder de quién sabe qué otro residente ilegal en París, urdía Karimi cuando recorría los pasillos encristalados y aéreos, y mientras viajaba por las esteras del gigantesco aeropuerto.

Pero lo que comenzó con marcados trazos de una auténtica aventura, terminó de sellar su drama. Perpetuo viajero ilegal, ciudadano de ningún lugar del mundo, es rápidamente cogido en falta por la policía francesa, que por no tener pasaporte lo encarcela cuatro meses, hasta decidir que carece de condiciones para deportarlo a país alguno. Con 46 años, el "apátrida más famoso del mundo" –así lo conocen– solo tenía ante sí el desamparo.

Ardía de indignación y lo paralizaba un cansancio amazónico. Pero decidió coger el toro por los cuernos: en vez de lamerse las heridas, se imponía levantar el ánimo y luchar por la sobrevivencia, que por cierto, es el más fuerte de todos los instintos. Mientras trueca en lecho varias sillas, en armario y biblioteca un lote de maletas y cajas, y se procura el sustento en el verdadero avispero que es la zona comercial de la Terminal No. 1 del mayor aeropuerto del orbe, va aprendiendo a sortear la dictadura del tiempo.

Un serio golpe le llegaría de la misma Bélgica, porque al intentar nuevos documentos como refugiado, sus autoridades se niegan a enviarlos por correo. Solo en 1995 aceptaron los belgas que volviese a recogerlos, pero bajo dos condiciones: que se quedase a vivir para siempre, y bajo supervisión de un trabajador social. Una especie de exilio involuntario que Nasseri –con siete años de aeropuerto y ya con algunos signos evidentes de desórdenes mentales– decide rechazar.

|

|

|

Sir Alfred, como lo llaman sus amigos del aeropuerto, ya tiene 60 años y está afectado física y psíquicamente |

Así, cuando en 1999 el gobierno francés le entrega un permiso de residencia y con él la posibilidad de moverse por Europa, también lo rechaza. A esas alturas ya no se reconocía en su nacionalidad de origen, ni en su propio nombre. Ocurre que todos lo conocen por Sir, Alfred, la fórmula usada –coma incluida– en una carta que le remitiesen las autoridades migratorias británicas.

Con el correr de días, semanas, meses y años, ante aquel singular y singularizado hijo de la indolencia se habían ido develando los más negros defectos y las mejores virtudes del género humano. Porque mientras se multiplicaban las gestiones y las idas y venidas judiciales, a su alrededor creció un tejido solidario formado por personal de las aerolíneas y de la red de servicios de la Zona Comercial de la Terminal No. 1 del Charles de Gaulle.

Es entonces, y no exagero un ápice, que esas fraternas y humanitarias actitudes logran eclipsar las peores acciones de que había sido objeto. "Es una compañía muy agradable, se nota que procede de una buena familia. Se ha ganado la simpatía de todas las autoridades del aeropuerto y le dejan vivir aquí", explica una dependienta de la farmacia de la terminal, que le permite usar su teléfono.

Se asegura, por ejemplo, que el médico y el cura del aeródromo clasifican entre sus mejores amigos. "Le da miedo abandonar la burbuja en la que ha vivido estos años", certifica el doctor jefe médico del aeropuerto y su galeno particular. "Tiene sus papeles en regla, medios económicos, pero no quiere irse porque solo existe a través del aeropuerto."

Los mimos de otros muchos le procuran el alimento, la vestimenta y hasta las buenas lecturas, sin olvidar la prensa diaria. Como a pesar de su cierto –y lógico– desequilibrio no ha perdido su dignidad, no permite que se le trate o considere un mendigo, a todo dar, un náufrago de tan complejo mundo. Es más, no faltan sorprendidos al saber que aún en medio de su metamorfosis, logre Karimi mantener su aseo y buen gusto en el vestir.

|

|

|

Tom Hanks, caracterizado como Nasseri |

Para la mayoría de los 35 millones de viajeros que circulan anualmente por el Charles de Gaulle Sir Alfred es un pasajero más que espera su vuelo. Tampoco para él resultan particularmente atractivos tales viajantes: "La gente que pasa por el aeropuerto no me interesa", dice. Pero le gusta recibir correspondencia, y que lo entrevisten. Hasta posa para las fotografías.

Ahora, mientras se adapta a la fama, guarda una libreta de banco con la gruesa suma que le pagaron los productores de la película de Spielberg por los derechos a usar su historia. "Puedo comprar lo que quiera, pero si es algo costoso me preocupa que se pierda o que me lo roben. Como mejor, y puedo comprar tiques de avión, pero mi estilo de vida es el mismo." También acaricia la idea de viajar al continente americano, porque de Europa no quiere saber mucho más. Mientras, escribe un diario y un libro sobre su vida.

En tanto, y por su bien, en la Terminal todos confían que logre arrancar sus ataduras mentales y abandone los predios donde ha vivido tantos años. Él mismo ha confesado que no es normal quedarse tanto tiempo en un aeropuerto. "Es muy aburrido."

Muchos que desconocen estos pormenores dicen que La Terminal no es creíble, aunque reconocen su genialidad como fábula y como comedia. Lo cierto es que más allá de tratarse de un filme magistralmente actuado y dirigido –lo digo como cinéfila y no como especialista de cine, que no lo soy– esta es una historia real sobre los atropellos y abusos que pueden llegar a cometer las instituciones básicas de la sociedad capitalista. Una historia, además, de racismo, xenofobia, e indolencia, porque quedaría por ver si en igualdad de circunstancias –y retorna la palabreja–, un ciudadano del Norte opulento habría llegado a sufrir tamaña infamia.

(28 de octubre de 2005)