|

|

El éxito de Padura comenzó

mucho antes de que este siglo naciera. La

génesis del triunfo entre el público cubano

tiene un nombre que hoy es mito: Mario Conde. (Foto:

Liliana Batista Esquijarrosa) |

Por: Yoel Suárez Fernández

Él no me conocía más allá del

teléfono. Yo lo vi en persona por primera vez el día

anterior. Cuando la Sala Villena se abarrotó de

seguidores y curiosos que buscaban el último libro del

escritor cubano más leído en la Isla y el extranjero.

Puntuales nos encontramos a la

entrada de la UNEAC. Me adelanté a sus pasos. Los ojos

saltones del hombre buscaban al estudiante de periodismo

con el que había quedado aquella tarde serena.

Pronuncia mi nombre. Asiento.

Extiende el brazo. Saludos, presentaciones, ella es

Liliana, tomará fotografías. Mucho gusto. Síganme; vamos

a otro lugar; a casa de una amiga para conversar mejor.

Antes de alcanzar la calle llegaron nuevos saludos. ¡Padura!

¡Leonardo! ¡Compadre! El escritor da la vuelta. Estrecha

manos, corresponde atento a la charla, y finalmente se

escabulle para memoriaguiarnos al auto.

…Leonardo Padura Fuentes es el

novelista cubano más publicado en el exterior. También

el más vendido. En la Isla es el más buscado. Y fíjense

que digo buscado. Porque su obra reciente (quizá la más

atractiva) no cuenta con las tiradas amplísimas de otros

autores, a pesar del interés de un público lector que la

persigue a ultranza…

La casa de Vivian Lechuga, su

editora cubana y amiga de años, nos sirve de refugio

para grabar la entrevista. La mujer nos acoge sonriente,

y promete una colada de su mejor café. También nos

recibe Goya, un cocker spaniel sordo que acude a las

manos de Padura como si reconociera en ellas a un amigo.

Un apagón matutino dejó a media

luz la casa, y ahora la tarde avanzaba tragándose el

resto del sol. Vivian despeja la sala para que

conversemos, y sin decir palabra se mete en la cocina.

Leonardo se acomoda en un mueble en forma de L; Liliana

y yo lo imitamos.

…El éxito de Padura comenzó mucho

antes de que este siglo naciera. La génesis del triunfo

entre el público cubano tiene un nombre que hoy es mito:

Mario Conde. Un detective sui géneris que, paralelo a

sus casos, desnuda a la sociedad con una crítica audaz.

La serie de novelas con el investigador al centro fue un

homerun editorial para la Cuba de entonces.

Pero el volcán Padura haría erupción más adelante;

tiempo después de otros libros de entrevistas sobre

música y deporte. La auténtica polémica arribaría al

panorama literario con propuestas con La novela

de mi vida, y su trabajo periodístico en la

agencia IPS…

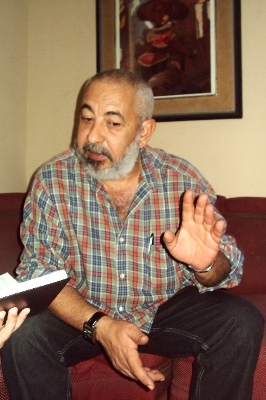

La barba nevada se adueña de un

breve mentón, de mejillas, hasta quedar conectada con la

blancura del pelo a ras del cráneo. Como un abanico se

abre una mancha oscura de vellos justo bajo la boca. El

rostro abultado tiene una expresión taciturna si

responde a una pregunta. Busca un punto invisible en el

piso hasta que ha terminado de hablar. En cambio, si

espera ser interrogado enfrenta a su interlocutor dos

ojos prominentes, y el amplio matiz expresivo que sus

cejas le permiten. A veces parece que busca en las

palabras algo agazapado, que tratara de ocultarse. Quizá

espera le pregunten lo mismo de todos los días; lo mismo

en las tres entrevistas que concede por semana.

La crítica que Leonardo hace de

circunstancias, pasajes e incluso la historia misma,

resulta deleitable. No es un ataque burdo a lo

sacralizado; ni una burla despiadada a las desgracias de

Cuba; tampoco es la detracción a la esencia de la

Patria. Padura juega con elementos prohibidos en el

borde de la hoguera. Mezcla su fino humor con la fórmula

de lo silenciado, lo vedado, lo provocativo… pero en la

exacta medida, para que la receta no se vuelva de veneno…

El caso es que este autor no es

del agrado de todos. La crítica duele a los responsables

del mal. Quienes conocen su obra figuran en Leonardo a

un polemista incansable. Me consta que inspira las más

violentas pasiones. Pero fuera de excepciones, millones

de lectores disfrutan y acosan la obra de Padura, que no

más publica un libro lo desaparecen del mapa (y saben a

qué me refiero).

…Leonardo ha sido (junto a Daniel

Chavarría) el novelista criollo más laureado fuera de

fronteras en las últimas dos décadas. Pocas veces el

nombre de Cuba se ha elevado a planos de tal prestigio

literario. En este sentido merece especial alusión su

última obra ficcional: El hombre que amaba a los

perros. Un volumen que tiene como eje sucesos

relacionados con la vida del asesino de Trotsky (un

extremista español que pasó sus últimos años en la mayor

de las Antillas). El texto ha encontrado la gracia de

expertos fuera y dentro del caimán. Ha recibido entre

otros lauros el; el Roger Caillois; y el Premio de la

Crítica 2011. No obstante, los medios de comunicación

tradicionales han permanecido inmutables ante tal

avalancha de galardones…

|

De tres mil ejemplares fue la

tirada que hizo Ediciones Unión de la más

reciente novela de Padura, El hombre que

amaba a los perros.

|

“Mira –me alerta con voz gruesa.

Aproxima hasta mí tres cuartillas engrapadas, llenas de

datos impresos-, estas son la cantidad de referencias

que ha hecho la prensa francesa al éxito de El

hombre...

se

quita los espejuelos- y aquí, en mi país, las personas

se enteran de estos acontecimientos por publicaciones

extranjeras. “

…Leonardo no se confiesa amante de

los premios, al menos no de esos que tradicionalmente

nos indica la palabra. Prefiere los premios verdaderos,

como es, por ejemplo, la estima del lector. Un lauro más

permanente que el de las instituciones…

El propio pueblo cubano -con su

instinto fabulador- ha creado toda una mítica, entorno a

la novela. Se dice que en la última Feria del Libro

(2011) no se vendió la cantidad de ejemplares prometida,

y que un buen número de las copias de la Editorial Unión

siquiera llegó a las estanterías. Simplemente se

esfumaron. En medio de ese ambiente enrarecido se han

pronunciado los rumores más variados: recursos, política,

derechos de exclusividad…El inventario de causas

posibles es variopinto, pero el más mínimo soplo lo

cierra a la certeza, porque en verdad, hasta hoy, Padura

no ha hablado del tema.

Un nuevo caso para Mario

Conde

La tirada que Ediciones

Unión hizo de El hombre que amaba a los perros

ha gestado las más disímiles habladurías. Se ha

rumoreado que median motivos de carácter económico o

político. No hace mucho alguien me explicaba que un

sello español tiene derechos de exclusividad sobre la

reproducción de la obra… En fin, ¿quién tiene la razón?

Te cuento cómo es la historia.

Desde el año 1996 he hecho contrato para cada una de mis

novelas con una editorial de España: Tusques. Cuando en

ese año gané el premio Café Gijón, ellos

leyeron la novela Máscaras, les gustó,

y por eso sale publicada en 1997 por esta editorial.

Después de Máscaras

vino Paisaje de otoño,

recuperaron Pasado perfecto y

Vientos de Cuaresma (que ya estaban publicados

en Cuba y México), y luego fueron saliendo La

novela de mi vida, Adiós Hemingway,

La neblina del ayer. Y ahora han

publicado una edición de La cola de la serpiente

(aquel relato que venía con Adiós Hemingway

en la edición cubana), y, en 2009, El hombre que

amaba a los perros.

Desde que comenzó esta relación

editorial Tusques le da un permiso a Ediciones Unión

para que haga una tirada, que es vendida en moneda

nacional para los lectores cubanos. En ocasiones a

Tusques se le ha pedido permiso, incluso, para hacer una

reedición de algunas de mis novelas y siempre ha dicho

que sí. Al igual que ha dicho que sí a la cantidad de

ejemplares que la editorial cubana pida. Para la edición

de El hombre… Unión pidió tres

mil ejemplares porque era el papel que tenía para

publicar, y Tusques dio permiso para tres mil libros. Si

le hubieran pedido cuatro mil o cinco mil igualmente se

le hubiera dado. A pesar de que muchos de esos libros

impresos aquí salen del país por varias vías.

Existen comentarios de que

durante la Feria del Libro no se vendieron la cantidad

de ejemplares prometida, y que un buen número de copias

no llegó a las estanterías. Que simplemente

desaparecieron. Los más osados apuestan a que fueron

robados. ¿Está enterado de estos rumores? ¿Puede

sacarnos de este ambiente enrarecido?

Desconozco realmente qué cantidad

de ejemplares se vendieron, si en verdad hubo esos

cuatroscientos libros que se perdieron misteriosamente

del almacén. No sé nada.

Estoy al tanto de que han habido

ejemplares que vendidos a diez, quince, veinte CUC, por

vendedores de libros viejos, y gente que se dedican a

eso; que en Revolico. com ha estado el libro en venta…

¿¡En Revolico!?...

Pero los detalles de lo que

ocurrió, realmente, no los conozco, tampoco me he

preocupado demasiado por investigarlo, tengo que

investigar otras cosas que son mucho más interesantes

para mí, y esto…bueno, pasó, y no sé exactamente lo que

ocurrió.

Los cubanos que no

alcanzamos a comprar El hombre… en la

pasada Feria del Libro, ¿podemos guardar la esperanza de

una reimpresión?

Debe haber una reedición, porque

por lo general, los libros que ganan el Premio de la

Crítica son reeditados. Y espero que ya Ediciones Unión

le haya pedido permiso a Tusques, porque lo que supe es

que varios meses después de que se había hablado esa

posibilidad, aún no le había escrito a Tusques pidiendo

permiso.

En fin, todo depende de la

cantidad de material que Unión quiera poner para una

reedición.

LA HISTORIA PARA ENTENDER

EL HOY

Ya se adelantaba en algo

de lo que quería hablar, y es que este 2011 mereció el

Premio de la Crítica y su obra tuvo una acogida

extraordinaria en la Isla. Especialistas y lectores han

elogiado su estilo ¿Esperaba tal éxito?

Mira, lo de los premios es muy

aleatorio. Puede ser que un libro como La novela

de mi vida, la que yo considero mi

mejor novela -porque es donde hay un mayor equilibrio

entre la proposición literaria y lo que consigo

literariamente-, no haya tenido el mismo éxito. En

cambio, creo queEl hombre… ha

encontrado una comunicación especial no sólo con los

lectores de Cuba y fuera de Cuba, sino también con

determinadas instituciones.

El primero de los premios que ganó

fue el de los libreros independientes franceses. Después

ganó el Francesco Guelmi, que se le concede a

la mejor novela histórica publicada en Italia. El

Roger Callois,

y el Prix Calbert que se da para escritores

del Caribe; y además, fue seleccionada la mejor novela

histórica del año, en Francia.

La obra ha obtenido premios que me

satisfacen mucho y no los esperaba. Y que creo ayudan

mucho a la difusión de la novela y a una presencia mayor

del volumen no solamente en los medios, sino también en

las librerías. Porque, como se sabe, a la semana en

países de Europa y en Estados Unidos los libros

envejecen, todo muy de prisa, y este tipo de cosas

permiten que El hombre… permanezca

mucho más tiempo en circulación.

Como decía, en abril de

2011 El hombre… mereció el Premio

Francesco Guelmi di Caporiacco, adjudicándose el primer

escaño en Novela Histórica por encima de 32 obras en

competencia. Cuando escribía la obra, ¿hasta qué punto

pensaba darle un enfoque historicista?

No creo que tenga un enfoque

historicista. Es que no me interesa escribir novela

histórica para contar una época. Me interesa mirar la

historia para entender el presente. Por eso tanto en

La novela de mi vida, como en

El hombre que amaba a los perros, o enLa

neblina del ayer,las historias en el pasado

siempre tienen unas consecuencias en el presente. La

historia es una continuidad de acontecimientos con

causas y consecuencias, que van conformando un proceso

que en algún punto nos toca la espalda. Ese es el

presente. Y entenderlo me parece tan importante como

estudiar lo ya acontecido. Voy en busca de determinadas

claves del pasado para expresar un entendimiento del

presente. Por eso no creo que escriba novelas

propiamente históricas.

Hace poco una importante

intelectual cubana recordaba sabiamente que nuestro

Martí no había recibido más premio que una medallita

escolar por una buena composición. Teniendo en cuenta

esta gran ironía histórica, ¿cuánto cree que las

premiaciones legitiman a un escritor?

La capacidad de legitimización de

un premio, depende de su propio prestigio. Como se sabe,

hay galardones –en España pasa mucho- que entregan

sellos editoriales, premios millonarios, concedidos bajo

determinados condicionamientos. Generalmente se les dan

a autores de la casa editorial, a autores que quieren

sumar, o a un libro que prometa un buen negocio. Hay

otros premios que son menos jugosos económicamente, pero

tienen un prestigio mucho mayor. Ese es el caso del

Roger Caillois. Y eso se ve sólo con detenerse en

la lista de galardonados tan notorios: algunos de los

autores indiscutibles de la lengua.

El premio es uno de los mecanismos

para legitimar una obra; el mercado es otro recurso,

aunque no siempre dice la verdad.

Me contabas lo de la medallita de

Martí, y te puedo recordar que el pintor más cotizado en

el mercado en algunos momentos ha sido Van Gogh, y en

vida no vendió una sola pintura, y no por eso deja de

ser un maestro.

|

De tres mil ejemplares fue la

tirada que hizo Ediciones Unión de la más

reciente novela de Padura, El hombre que

amaba a los perros.

|

Es decir, a veces los

reconocimientos y el mercado no acompañan una buena

obra. También, qué ocurre: en los últimos treinta,

cuarenta años, el sistema de estímulos literarios ha

crecido muchísimo. Y al ocurrir esto, su carácter

legitimador se ha distendido. Afortunadamente algunos

premios todavía conservan la honestidad, como hay otros

que uno ya sabe quién lo va a ganar y las razones por

las cuáles lo gana.

ROGER CALLOIS, EL SILENCIO

Y EL PREMIO VERDADERO

Este noviembre asaltó a no

pocos medios internacionales con el titular de que por

primera vez un cubano se alzaba con el prestigioso

galardón literario Roger Caillois. ¿Qué significa para

usted incluirse en una lista donde ya leíamos nombres

como Carlos Fuentes, Adolfo Bioy Casares, entre otros

grandes de Latinoamérica?

Creo que lo más importante del

premio es eso. La dotación económica es simbólica. Es un

lauro que hacia el interior de Francia no es tan

importante como hacia el exterior (América Latina,

fundamentalmente). Y sobre todo es un premio que lo han

ganado algunos de los autores más grandes todavía vivos

y actuantes durante los últimos veinte años.

Nunca se le había conferido a un

cubano (a los que viven fuera o dentro de Cuba). Me lo

otorgan por el conjunto de mi obra, y muy impulsado por

lo que ha sucedido con El hombre que amaba a los

perros. Y resulta curioso que

la repercusión de este suceso haya sido mucho más

importante en otros países (como España, México,

Argentina, Chile) que en la misma Cuba. A veces me

pregunto qué razones deben existir para que no se valore

adecuadamente el hecho de que un escritor cubano –con

independencia que se llame Leonardo Padura- gane un

premio de este tipo.

Creo que para la cultura cubana es

un reconocimiento muy importante, después de varios años

en los que no ha aparecido ningún escritor del patio

entre los más promovidos de la lengua. Y sin embargo,

hacia el interior ha existido esta sequía de información

respecto al tema. Yo recuerdo, en otras ocasiones

(cuando trabajé como periodista en el Caimán Barbudo,

La Gaceta y Juventud Rebelde) que un

acontecimiento así, hubiera significado en La Gaceta,

por ejemplo, dedicar un dossier al autor, dedicar un

número de la revista Unión, no sé, algo que

desde las redacciones culturales diera a entender la

magnitud de este suceso para la literatura nacional.

No sé cuáles puedan ser las

razones. Pueden ser desde carácter político hasta de

carácter personal. Puede haber una gama muy variada de

motivaciones para que esto ocurra, incluida la

mezquindad. Pero el hecho es que ocurre, y me parece

lamentable, porque muchas veces se habla de la

insuficiente promoción de la literatura cubana, de la

dificultad de la literatura cubana de llenar espacios

editoriales fuera del país; y cuando esto se revierte,

pues no hay reconocimiento alguno.

Sin embargo, de pronto te enteras

que un músico hizo un concierto en la casa de cultura de

la tercera ciudad más importante de Dinamarca, y sale un

cuarto de página en el periódico, se comenta en la

televisión. Y eso crea una desproporción en cuanto a la

posibilidad de valoración real de determinados

acontecimientos artísticos que tienen mucho que ver con

lo que está ocurriendo en Cuba hoy en las diferentes

manifestaciones artísticas.

Creo que el pollo del arroz con

pollo está en lo siguiente: Mientras hay poco

reconocimiento institucional, yo me siento muy, pero muy

realizado con la relación que he desarrollado con los

lectores cubanos. Una novela con El hombre que

amaba a los perros fue muy difícil de escribir,

porque es una obra en la cual tuve que pensar en dos

lectores: uno cubano y uno no cubano. Esto, debido a la

capacidad de acceder a información que hemos tenido casi

todos en Cuba. No de que alguien la tengan (puede que

una persona u otra tenga información), sino a la

capacidad de acceder a información por parte de estos

dos lectores potenciales.

Por ejemplo, un lector extranjero

puede ponerse rápidamente al día en lo que fue la vida

de Trotsky, los Procesos de Moscú, los últimos textos

sobre la República Española y la presencia soviética en

la Guerra Civil. Pero un lector cubano, no. Por lo

tanto, mientras me llenaba de información para escribir,

y después, cuando escribía tuve muy en cuenta que debía

complacer y llenar las expectativas literarias de ambos

lectores; y que además, tenía que colmar las

expectativas informativas del cubano. Y eso es muy

complicado en la narrativa, porque la novela no está

para explicar. La narrativa muestra, sugiere, dibuja una

realidad; pero no es un ensayo para exponer un concepto,

por ejemplo.

La respuesta que he tenido del

lector nacional (desde mucho antes que fuera publicada

El hombre…) constituye el

reconocimiento más grande al que puede aspirar un

escritor…

…Padura coagula el

diálogo. Detiene las palabras como un tren poco a poco

la marcha. Levanta el rostro, y las manos reciben el

blanco pelaje de Goya. Vivian llega hasta nosotros

envuelta en el aroma del café recién colado. Dispone las

tazas en una mesita cercana. Te traje un poquito de

agua, Leonardo le dice que sí, que qué bien hizo en

traerle, porque como está hablando se le saca la

garganta. Vivian se retira sigilosa, no sin antes

preguntar si alguien más quiere agua. La tacita de

porcelana con detalles de Portocarrero se pierde en la

anchura de las manos del escritor. Bebe lentamente; y

cuando acaba el café llega el tiempo de fumar. Busca la

cajetilla en la camisa. Desenvaina un cigarro y expone

la punta al fuego. Todo en silencio, como si fuera un

ritual. Sale denso de su boca un buche de humo gris.

Mientras, el cigarro humea tristemente en una mano como

si hubiera perdido la vida con la última fumada. En

cuanto despide la primera bocanada retomamos la

entrevista…

…Te decía, que ese reconocimiento

tan importante (que ha sido patente y evidente) por

parte del público, es el que sustenta que pase algo como

lo de ayer. Cuando la presentación de un libro de

periodismo (La

memoria y el olvido, Editorial Caminos), se

convierte en un acontecimiento social más que cultural,

con más de doscientas personas que llegaron a la sala

Villena de la UNEAC aún cuando hubo una escasísima

divulgación (afortunadamente, porque si no hubiera sido

un gran problema para los organizadores).

Y esto es una muestra del

reconocimiento del lector, que para mí es mucho más

importante que el reconocimiento institucional. Entre

otras cosas porque las instituciones cambian, los

directivos también; los jefes de revistas entran y salen

(aunque en Cuba a veces la gente dura demasiado al

frente de un centro de cualquier tipo). Pero la gente

que vive en un país, si bien cambia, es mucho más

permanente que las personas al frente de determinadas

instituciones.

PRÓXIMAS HEREJÍAS

¿Se confiesa un amante de

los premios?

No, no. Soy un amante, sobre todo,

del oficio de escribir. Soy un escritor que trabaja

todos los días, aún en condiciones bastante complejas

(porque la vida cotidiana y la profesional a veces te

llenan las mañanas de complicaciones). Soy un hombre que

se levanta temprano y todos los días está en función de

la literatura. Cuando no es una novela escribo un

ensayo, hago periodismo, preparo un guión de cine, un

prólogo o una conferencia. Siempre estoy trabajando

porque no sé hacer otra cosa que trabajar.

He tenido una inmensa fortuna con

los premios y el mercado. Y es que mis libros se venden

en una cantidad suficiente que me permiten vivir de mi

literatura y sobre todo, vivir para mi literatura. Ahora

mismo estoy en medio de un proyecto de novela que hace

dos años comencé a trabajar (pocos meses después de

terminar El hombre…); y me va a llevar

un año más de trabajo. Requería una etapa de

investigación y búsqueda de información que debía hacer

básicamente en España y Holanda. Pude viajar a ambos

países (pagándolo de mi bolsillo). Y puedo hacerlo con

una relativa tranquilidad, porque los libros anteriores

me permiten dedicarme por entero a este nuevo libro, y

espero que cuando lo termine este libro, él también me

ayude a terminar el siguiente.

¿Sabes?, ese es un elemento del

que no se habla demasiado: la seguridad económica del

escritor. Creo que el artista contemporáneo –por las

condiciones del mundo en que vivimos- necesita cierta

seguridad económica. No estoy hablando de riquezas o

yates; sino de esa estabilidad que te permite escribir

con la tranquilidad de saber que la comida que va a

comer ese día, la gasolina que le pondrá al automóvil o

la electricidad que pagará para que la computadora

funcione no se le va a convertir en un problema. Y eso

ayuda muchísimo al artista. Le da seguridad y, más aún,

le garantiza independencia.

Me hablaba de una próxima

novela. ¿Tiene un título provisional? ¿Qué historia

cuenta esta vez?

Pensé que se iba a llamar

Los Herejes. Pero me di cuenta de que hay una

hilación fonética entre palabras; y entonces le voy a

poner simplemente Herejes.

Es una novela que cuenta cuatro

historias, que tienen conexiones y desconexiones entre

sí. Cronológicamente, aunque no es la inicial en el

libro, la primera es la de un judío sefardí que vive en

Holanda, en la época de Rembrandt, y quiere ser pintor.

Para los judíos estaba prohibida la representación de

figuras, pero este hombre se acerca al gran creador,

entra a su estudio y ahí se produce toda una reflexión

sobre la decisión de este hombre de violar una ley

Mosáica, y el conocimiento de la pintura a través de

Rembrandt, en un momento en que Holanda es el lugar más

rico y libre del mundo, y donde, sin embargo, hay

libertades que no son permitidas.

Este sefardí pinta un cuadro, y

esta pintura tendrá conexión con una historia que ocurre

en la Cuba de los años 40 y 50, con un judío asquenazi

(de Europa del Este) llegado a la Isla de niño. Sus

padres iban a venir a Cuba en un barco famoso por su

historia trágica (el San Luis) donde, además,

llegaría la pintura. Y aunque no los dejan desembarcar

en La Habana, con el tiempo aparecerá en Cuba aquel

misterioso cuadro.

En Herejestambién

trato la historia de este hombre que, renunciando

cultural y religiosamente a su condición judía, se

convierte en un cubano. Después este individuo se va a

Miami en el 58, por algo que ocurre en la Isla; y es

entonces que la historia se conecta con un personaje que

ayudará a la revelación de este misterio: Mario Conde.

Un hijo de ese judío asquenazi que

se fue a Miami, viene a Cuba para entender por qué su

padre se fue y por qué no llevó consigo el cuadro que

formaba parte del patrimonio familiar y busca la ayuda

del Conde.

Mientras, Conde está investigando

la desaparición de una muchacha emo, que

también optó por su libertad, se aportó de todos para

participar de una tribu, y desaparece en el momento en

que ha decidido dejar de ser emo.

Es una novela que tiene mucho que

ver con las decisiones de los individuos, con la

búsqueda de reafirmación, de una opción de libertad para

las personas, que casi y en algunos casos sin casi, pasa

la línea de lo herético.

Cubre un arco de trescientos años,

con personajes completamente diferentes, pero que en un

momento determinado toman la decisión de optar por su

libertad individual.

|

|

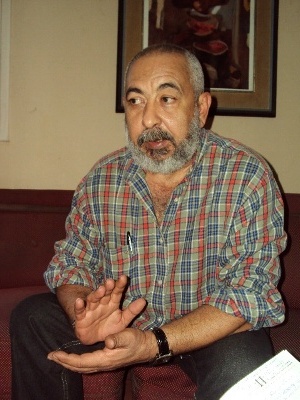

“Debe haber una reedición,

porque por lo general, los libros que ganan el

Premio de la Crítica son reeditados”, dice

Padura. (Foto: Liliana Batista Esquijarrosa) |

El trabajo investigativo

debe haber sido muy complejo…

La parte más compleja ha sido

entender la cultura y el pensamiento judíos, porque no

hemos vivido entre judíos. Nos es mucho más fácil

comprender una religión afrocubana, aunque no la

practiquemos, a entender el judaísmo que tiene más de

cuatro mil años, toda una historia riquísima, y un

pensamiento complejo.

También fue difícil aprender a

pintar como Rembrandt. Aunque soy incapaz de coger un

pincel y dar dos trazos, pero pude asimilar el concepto

renovador de la pintura de Rembrandt, que entregó las

artes plásticas barrocas a la modernidad de manera

asombrosa. Me ha obligado a estudiar muchísimo.

PERSONALÍSIMO

El año pasado nos llegaba

una buena noticia: Padura hará otra vez de guionista…

Cómo le fue con esos Siete días en La Habana.

En este caso no era propiamente un

largometraje, porque son siete pequeñas historias. Mi

esposa –Lucía López Coll- y yo, trabajamos escribiendo

una serie de argumentos para que los posibles directores

escogieran qué historia le interesaba.

Algunos escogieron de esos relatos,

y algunos nos pidieron que escribiéramos el guion. Lucia

y yo trabajamos en el guion de los cuentos que

dirigieron Benicio del Toro, Juan Carlos Tabío, Julio

Médem, y el argumento del cuento de Trapero, el

argentino. Los de Laurent Cantet, el francés, Solimán,

el palestino, y Gaspar Noé, son ideas independientes.

Fue una labor bastante grata.

Tenía experiencia en largometrajes, en cortos y

documentales. Pero creo que el trabajo en esta película

me reafirmó la idea que siempre he tenido: los

escritores no deben escribir cine, porque siempre se

queda uno con un sentido de insatisfacción, en la medida

que es un trabajo de servicio, en el cual escribes lo

que necesita un director, o un productor, o los dos a la

vez. No es un trabajo en el que tu creatividad es la que

decide qué cosa se escribe, sino lo que esperan el

director o el productor que tú escribas.

Prefiero no escribir cine, lo hice

en ese caso, porque recién había terminado El

hombre que amaba a los perrosy necesitaba

alejarme de esa novela. Apareció ese proyecto, era

económicamente rentable y artísticamente atractivo, y

por eso decidimos Lucía y yo meternos en él.

Ahora se está negociando la

posibilidad de hacer algunas películas con algunas de

mis novelas, -incluidoEl hombre que amaba a los

perros-, y yo no quiero trabajar en los guiones.

Sin embargo, sí voy a trabajar con Laurent Cantet, en un

guion a partir de una idea, un punto, de La

novela de mi vida, y aunque va hacer una

historia completamente aparte, el origen está ahí, en el

libro.

Y lo voy hacer porque realmente

creo que trabajar con un director del nivel de Laurent

Cantet es un privilegio que poquísimos escritores tienen.

Pienso que él es un hombre tocado por el cine y con

quien, a pesar de que nos comunicamos en inglés —él no

habla español, yo no hablo francés—, lo cual hace que

nos falte a los dos la sutileza, hemos logrado una

comunicación muy armónica en las cosas que hemos ido

trabajando y hablando. Y quiero hacer ese trabajo con

Cantet, posiblemente este verano.

Durante la reciente

presentación en la UNEAC de su libro La memoria

y el olvido, se refirió a los 80’ como una etapa

que desde su mirada actual le parece un período

artificial. ¿A qué se refería?

Sí. De pronto fue un período en el

que en Cuba había cosas, se vivía bastante bien, había

más guaguas que en otros años, había más comida que en

otros años, había más ropa, más café, más ron, más

cigarros. Había más de todo.

Pero cuando llegó el año 1990, la

caída del Muro de Berlín, el principio, y después en el

91, la desintegración de la Unión Soviética, nos dimos

cuenta de que todo ese estado de bienestar que se había

logrado en la Isla era absolutamente artificial. Se

debía a una inyección de capital soviético, y de los

países del Este, y que Cuba por sí sola era incapaz de

generar tal riqueza.

Todavía estamos pagando las

consecuencias de eso, y secuelas de cosas que ocurrieron

después incluso. Nos dimos cuenta por ejemplo, de que en

esos años se hubieran podido hacer cosas sustanciales en

Cuba a nivel industrial. Quizá la cosa más importante

que se puede hacer en nuestro país, algo que es

absolutamente imprescindible es una fábrica de

ventiladores, una buena fábrica de ventiladores. Aquí

hay dos cosas sin las cuales no se puede vivir: un

refrigerador y un ventilador. Sin el refrigerador no

puedes guardar comida -y en Cuba hay que guardar

comida-, y sin el ventilador no puedes dormir en verano

-y necesitamos dormir todos los días. Entonces, fuimos

un país que tuvo ese estado de bienestar absolutamente

artificial, pero que además ni siquiera lo aprovechó

para lograr un futuro menos artificial, un poco mejor.

¿Quiénes son Vivian

Lechuga y Ciro Bianchi?

Vivian es, primero que todo, mi

amiga, y es la persona -fuera de Lucia-, que más me

complementa y ayuda. Edita mis libros, los lee, me

resuelve problemas cotidianos, que a veces son

complicados para alguien que vive en Mantilla; y tenemos

una relación de amistad muy, muy estrecha.

Ciro fue uno de mis primeros

modelos de periodista. Él lo sabe. Su periodismo siempre

fue un punto de atracción, allá por los finales de los

70, cuando yo no pensaba ya ser periodista, -porque yo

hubiera querido estudiar periodismo, sobre todo para

escribir de deportivas-, y después deseché la idea

cuando matriculé en Filología.

Imagino, el periodismo que

ejerció desde medios como Juventud Rebelde ha favorecido

el olfato investigativo para crear y recrear historias

como la de El hombre…

Mira, yo no soy periodista de

profesión, soy filólogo, y desde que estaba en la

universidad comencé a colaborar con el El Caimán

Barbudo, escribiendo críticas literarias. Y tuve la

suerte de que, al graduarme, estaba por cubrir la plaza

de corrector de esa revista. En el 80 empecé a trabajar

como corrector, y a los cuatro meses ya me convertí en

redactor. Ahí trabajé hasta el 83, cuando que me

expulsaron por mis problemas ideológicos, y me

mandaron para Juventud Rebelde.

Ese primer periodo en el El

Caimán fue muy importante, porque me permitió

entrar en contacto, en un nivel de igualdad, con los

creadores cubanos más significativos de aquellos

momentos. El Caimán era la revista cultural más

importante de Cuba, en esa etapa, y eso me nutrió

muchísimo. Ese es el período en que escribo casi

completa mi primera novela Fiebre de caballo,

y casi completo mi primer libro de cuentos Según

pasan los años.

Pero cuando voy a Juventud

Rebelde, tengo que aprender a hacer periodismo -aunque

en el proceso de aprendizaje, realmente apliqué lo que

ya conocía de la creación narrativa en función del

ejercicio periodístico. Así, muy pronto empezó a surgir

una mezcla de periodismo y literatura poco concientizada,

no era un proyecto, no era una teoría que estaba

tratando de aplicar, sino era las soluciones que tenía.

Claro, por mi desconocimiento de

las técnicas periodísticas, y por la necesidad de hacer

un periodismo que comunicara información, tuve la suerte

de que muy pronto empecé a trabajar en un equipo

especial que hacía el diario de los domingos. Aquel

periódico que hacíamos en Juventud Rebelde se

convirtió en una referencia que creo ya es histórica, me

atrevo a decir que uno de los momentos más… brillantes

de la prensa plana nacional. Uno de los momentos más

creativos, irreverentes, de mayor calidad en cuanto a la

creación literaria en la prensa.

Pero en esos seis años que trabajé

en Juventud Rebelde yo no escribí

literatura. Uno o dos cuentos, y uno o dos ensayitos muy

breves sobre Carpentier, porque me dediqué por completo

al periodismo.

Cuando en el 89 salgo del

Juventud Rebelde tengo la posibilidad de trabajar

en La Gaceta -oficialmente en el 90 y ahí soy

el jefe de redacción, hasta el 95. Pero en ese momento,

en 1990, yo comienzo a escribir Pasado perfecto,

y escribo un cuento que se llama El cazador. Y

me doy cuenta de que se ha producido en mí una

apropiación de la capacidad narrativa de construir y

contar una historia que no tenía antes de esos seis años

en el periódico.

Creo que en el diario viví una

importante etapa de creación,así lo siento -porque lo

considero una etapa creativa, no lo considero para nada

un oficio con el cual me ganaba la vida. Por eso todavía

muchos de esos trabajos son tan vigentes como los

cuentos y las novelas que escribí en aquel momento.

Antes de Juventud Rebelde yo era un escritor

absolutamente amateur, cuando empiezo a

escribir después que salgo del diario, soy un escritor

profesional.

Y a partir de ahí he ido

aprendiendo, aclarando y enfrentando desconocimientos;

porque cada vez que uno (por lo menos me pasa a mí),

cada vez que uno empieza a escribir una novela, tiene

que aprender a escribir esa novela, por mucho que crea

que ya sabe escribir novelas. El acto de la escritura de

un nuevo libro te impone nuevos retos, nuevas

necesidades de encontrar la mejor expresión para la idea

que quieres transmitir.

Por lo tanto es un aprendizaje que

no termina nunca -yo no quiero que termine nunca- y por

eso cada vez que finalizo un libro que parece muy

complicado, me propongo a hacer otro que sea más

complejo. Porque me sería muy fácil poder escribir ahora

una novela como Pasado perfecto, o

Vientos de Cuaresma, desde el

conocimiento literario que tengo ahora. Y me resulta muy

difícil hacer una novela como Herejes

porque estoy aprendiendo a escribirla mientras la

escribo.

La Habana,1ro de Febrero de 2012 |