http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2010/12/28/enrique-molina-la-vida-nos-vuelve-a-levantar/

Enrique Molina: “Life gets you back on your feet”

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

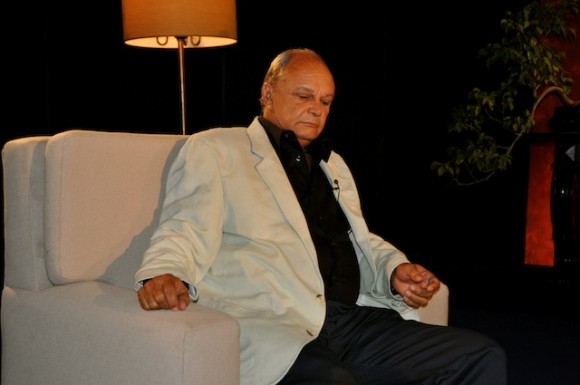

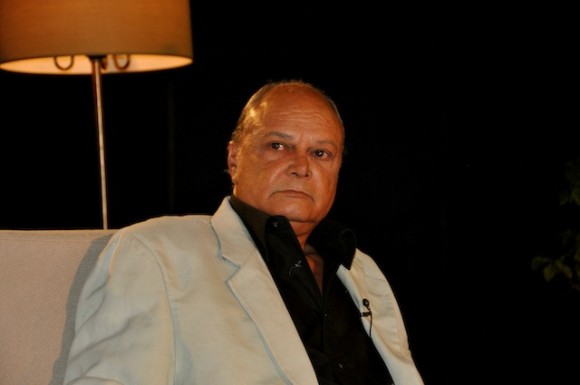

Enrique Molina in “Con dos que se quieran" [1]

(Photo: Petí)

Amaury:

Good evening! This is your program Con dos que se quieran, from

the recording studios of the Cuban Film Institute on Prado and Trocadero,

[late Cuban writer José] Lezama’s neighborhood, in the heart of Centro

Habana municipality.

It’s a new privilege to me to have here with me one of our brightest and

most popular and consistent actors. Simply put, and using a term I very

rarely chose, I give you the magnificent Enrique Molina, my lifelong

buddy. Enriquito, how you do like talk shows? Do you find them useful at

all? There are plenty of them today, so tell me your general opinion,

because it would be vain and arrogant to ask you about mine.

Enrique:

Look, it depends; I don’t know if it’s because I don’t have anything

else to say that I always give the same answer, or it’s maybe because

unfortunately most journalists who interview me ask the same question.

When you invited me to come, I told myself that I would repeat again

what I’ve said before. Not that I want to, it’s because somehow you’re

afraid of stuffing viewers the same old lines.

Amaury: I’m sure you have already answered in other

interviews many of the questions I have for you, but there’s a lot of

people out there who probably were not around to watch them, or…

Enrique: Or they were just ten years old and couldn’t

care less…

Amaury: That’s right, but now they do. Besides, you’re

still playing roles because as an actor you’re not one to live in the

past. Let’s talk about the basics: you were born in the town of Bauta.

What was your life like there? Was it happy or sad, nice or poor? How

would you describe it?

Enrique: Life was very, very hard there. I was born in

1943, so as you can gather I spent in Bauta my first 15 years of life. I

had a wonderful family made up of the two races we have in Cuba: black

and white. My mother, her parents and all her brothers were white and

had green or blue eyes, but my paternal grandfather Juan, who owns our

family name Molina, was merely a lighter shade of the color of your

suit.

Amaury: (Laughing) Just a bit lighter?

Enrique: Only a trifle. I remember my mother developed

lung trouble when I was two and the doctors took me away to keep me

safe. She died two years later and my grandmother took me in, and she

felt so sorry for me that she became too affectionate and

overprotective. See, my father left my mother as soon as she fell ill

and went to live in the province of Camagüey, where I think he got

married again and all that. So my grandma went out of her way to keep me

by making a lot of sacrifices until the triumph of the Revolution, when

she decided to go live with a daughter she had in Santiago de Cuba to

take a break from the hard knocks she had taken in her time, and she

took me along because I was still a minor and she felt I was her

responsibility.

I had a hard childhood. At ten I had to drop out of a local public

school and spend the whole day doing a lot of stuff: at 8:00 a.m. I

would start selling avocados from a huge basket I could hardly keep on

my head and stop at 10:00 a.m. to start making lists of people who put

money on lottery numbers to make five or ten cents. In the afternoon I

would work as a shoeshine in the town park, and in the evening I would

sell peanuts in the former local movie theater. That’s how I lived…

Amaury: That’s how you lived your life as a child…

Enrique: That’s how hard it was. My cousins cleaned

floors for a living. I also washed cars in a garage called Lambín –the

owner’s name– on Bauta’s main street, and so on and so forth. Actually,

I was the rule, not the exception, because those were very difficult

times. It was the card I drew, and I remember it as it helped me develop

as a person.

Amaury: Was it as hard in Santiago de Cuba in the early

days of the Revolution or did you feel life was going gentler on you?

Enrique: Well, I had a friend there, Denis Morales, who

got me a job in a coffee shop near the park then called Dolores.

Amaury: Tell me how old you were then so I can follow

your time line.

Enrique: By then I was about 17. My job was to fill

boxes with bottles of soft drinks like Coca Cola, Orange, Materva, etc.

and take them out for the trucks to pick up. That’s when I started to

struggle to get on in life, with a job in that coffee shop. And that’s

where I met my first wife.

Amaury: How so? While you worked as a waiter in that

place?

Enrique: Yes. I met this woman, Marta Mestre, with whom

I had three children, my first family. I’m grateful to Santiago de Cuba,

although many people in the street tell me, “Hey, we’re homeboys, I’m

also from Santiago de Cuba.” But it’s impossible to make it clear to

everyone out there that I’m not from that city.

Amaury: Of course, but there’s no need to do that

either, everybody who is from Santiago is Cuban too.

Enrique: Sure they are, and I’m very happy that I lived

for 10 years in that city and started my adult social and professional

life there.

Amaury: We’ll get there. You were in Santiago when you

became a member of the Amateur Actors Movement, right? What did it mean

to you? I’m asking because that Movement doesn’t exist anymore.

Enrique: It doesn’t.

Amaury: It kind of faded away, didn’t it?

Enrique: It just disappeared.

Amaury: So many valuable people came from there, like

you…

Enrique: I started in a group of amateur actors who were

members of the local union of restaurant workers. ‘Nubiola’, the coffee

shop where I worked, was around the corner from Santiago de Cuba’s

Professional Auditorium where Oriente province’s former Drama Troupe

used to perform. Among them were Félix Pérez, [Raúl] Pomares, Obelia

Blanco, María Eugenia García and many others.

Amaury: Famous santiagueros, all of them.

Enrique: They would always come to the coffee shop for a

snack and we soon became friends, until Félix told me, “Hey, in two or

three days we’ll have auditions for new professional actors!” I showed

up together with Miguel Sanabria, but I didn’t pass. He did, though. I

went back to the coffee shop in very low spirits, and with good reason:

my salary there was only 69 pesos and I already had my first child,

whereas the Theater Troupe paid 150 pesos, a lot of money those days. So

I told myself, “No way, I have to convince someone there, I just have

to!”

Amaury: Boy, it sure was big money back then!

Enrique: Two or three days later Félix came to see me

again and told me he had talked to the Argentinean. He knew that I…

Amaury: Oh, because the managers were from Argentina?

Enrique: Yes, Adolfo Gutkin and Jaime Swetinzky.

Amaury: What on earth were those Argentineans managing a

Drama Troupe in the province of Oriente[2]?

Enrique: They were awesome!

Amaury: Were they good managers?

Enrique: Great acting directors. So Félix told me:

“Look, I talked to the Argentinean, you should audition again and see

what happens.” I went to see Adolfo Gutkin, the one who flunked me, who

was sitting in his office, and he just stared at me. Then he said, “OK,

now you go out that door, come again in a couple of minutes, and say the

only words I want to hear from you: ‘I want to be an actor. That’s all I

want, but you have to keep saying it in different ways until I tell you

to stop.” My God, in one of those times I even threw myself to the

ground, crying as if I was having a seizure: “I wanna be an actor!!!”

Then I jumped onto his desk, and I think even the strollers in Céspedes

Park could hear me crying that I wanted to be an actor.

Amaury: (Laughing) So sometimes you cried while saying

that?

Enrique: The Argentinean was laughing exactly like you

are now.

Amaury: No wonder, it’s the thought of you saying in

different ways that you wanted to be an actor!

Enrique: He was probably wondering, is this guy crazy or

what? In the end he said, ‘Look, you’re going to be an actor.’ I went

back to work and shouted, ‘Pedro Carrió, I’m an actor!’ So I quit my job

and joined Oriente province’s Drama Troupe. My first evening, you can

imagine, a meeting with the Argentineans and the whole cast discussing

Brecht, Stanislavsky, Grotowski,

Brecht and all those people I had never heard of. I thought, what am I

getting into, and felt like running like a bat out of hell. And from

there, I moved on by dint of…

Amaury: By dint of sheer talent, my man.

Enrique: Struggling and fighting.

Amaury: Very few have equaled your achievements. So did

you work in the radio while in Santiago?

Enrique: Yes, I did, at CMKC, but I’m terrible in radio.

Amaury: Do you?

Enrique: Awful.

Amaury: There’s no way you’re bad with anything,

Enrique.

Enrique: No, I’m very bad in radio, which is to me the

hardest to do. I can’t praise too mucho those actors who pick up a

script, have a quick look at it and start acting out what’s written

there. It’s very difficult, and I was not ready for that. I memorize

scripts at my own pace and take what time I need to get into the

character I’m going to play.

Amaury: You mean your lines.

Enrique: Only when I’m sure I got the hang of it all do

I tell the director, let’s rock.

Amaury: Do you also memorize the lines of those who play

opposite you or just your lines?

Enrique: No, no, you have to study everyone’s lines; at

least I do.

Amaury: Because some actors merely concentrate on their

cue.

Enrique: That’s right, and when you see them they always

seem to be at a loss, because the other one is talking and they’re only

waiting to hear the key word to say their lines. You do that and you’re

dead. No, no, no, I can’t work that way. I even do a psychological study

of the character opposite me in addition to mine. Otherwise, you can’t

have a connection.

Amaury: One thing about that connection, Molina: who

keeps the pace of a dialogue? Right here, for instance, who of us sets

the tone?

Enrique: You started by setting the tone of an interview

and I followed your lead. Then, at some point, I might pump it up a

little because I get mad or something.

Amaury: OK, OK, don’t get mad. (Laughter)

Enrique: No, I don’t get mad; what I usually do is match

up the tone of the interviewer.

Amaury: You mean the tone I set at the beginning?

Enrique: Right.

Amaury: So if I raise the tone a little because I think

I should be more emphatic, you tend to follow my lead, is that it?

Enrique: It is in this case, I mean, here and now. Not

when I’m acting, like when your character is having a fit of rage, for

instance.

Amaury: Like a madman who gets in a terrible flap?

Enrique: And all the while my character is in stitches.

Amaury: I asked you because the tone is vital to me as a

musician. So when did you come to Havana and why? You had a wife and

kids there. Did they all come with you?

Enrique: Well, things got complicated. This is very

personal, but what the heck, one comes to this program for confession,

as it were.

Amaury: Oh no, don’t say that.

Enrique: At least that’s how I feel about it. I really

liked very much the beautiful and very personal things Frank Fernández

talked about here.

Amaury: It’s just that my guests open up to me, which is

an honor.

Enrique: He talked about personal things that, I don’t

know, I found beautiful. Anyway, my marriage was fine while I was

employed in the coffee shop, but no sooner did I become an actor than it

began to get ugly. You see, I used to walk very often along Enramada

Street[3].

Amaury: A beautiful street.

Enrique: Besides, I was only 17 or 18, if you know what

I mean. And I was very handsome, truly a sight for sore eyes.

Amaury: Dude, you’re very cute.

Enrique: I was back in the day, my brother. That’s when

my marriage started to fall apart. She didn’t understand why I had to

spend so many hours rehearsing. And then there were all those women in

the streets who recognized me and wanted to have their picture taken

with this actor who starred in a play. It’s just the way it is in this

line of work. In short, something had to give, and the moment came when

I decided to break up. I came to Havana in 1970, and a few days later I

started dating the woman who is now my wife.

Amaury: You’ve been together for 40 years.

Enrique: That’s right, we have already celebrated our

40th wedding anniversary, and it has really really meant a lot to me. I

came from Santiago de Cuba with nothing but two trousers, three shirts

and 28 pesos in my pocket, in addition to a letter written by Enrique

Bonne stating that I was an actor.

Amaury: Enrique Bonne the musician?

Enrique: Yes, the musician, who was head of the program

planning division with [the TV channel] Tele Rebelde in Santiago de

Cuba, of which I was a founder. It was in Santiago where I shot from

theater to television, so he gave me a letter that said, “Enrique Molina

is a local actor” and so on, which might prove handy to find a job in

this city. One day I was talking with Carlos Quinta in front of the

coffee shop there used to be by the entrance to the Cuban Radio and

Television Institute (ICRT), asking him for a few helpful hints about

the rules of the game here, when he said suddenly, “Look, that guy

coming down the street is Abraham Maciques, ICRT’s Director-General. At

once I grabbed my suitcase, crossed the street and told him: “Excuse me,

I have a letter here signed by Enrique Bonne stating that I’m an actor

from Santiago de Cuba, and I’d like to know whether you can give me a

job.” He just stood there gazing at me like this… Ask him if you will,

for he will bear me out.

Amaury: Don’t worry, he won’t put up with lying.

Enrique: He took my suitcase, turned around, and told me

to follow him. We took an elevator, walked down this hall, took another

elevator to the 9th floor, and went into an office where he introduced

me to this guy Carlos Díaz, who was a casting director, and told him:

“Tomorrow first thing give this guy a program for the learning channel.”

I was in.

Amaury: That was quick!

Enrique: He asked me if I had a place to live, and when

I told him I had family in Bauta he gave me a key to a house they had on

Neptuno Street that he said was in very poor condition and had a room

with four or five beds, and he thought one was empty and I was free to

use it so I could have a roof over my head. And there I was, looking at

him in speechless wonder. It was one of those things life drops on your

lap that make me feel very happy and lucky and what not.

Amaury: Had you and Elsa met yet?

Enrique: Yes, we had already met. So I bunked in that

place for six months and then I married Elsa Ruiz, and now you see,

we’ve been together for 40 years and had two wonderful children.

Amaury: Your children…

Enrique: …I also have children in Santiago.

Amaury: And you also have grandchildren and

great-grandchildren.

Enrique: I have three great-granddaughters.

Amaury: Simply unbelievable! But then again, you started

very early.

Enrique: Very early, and so did my children.

Amaury: That figures, they took it from their father,

who at 17 already had two children.

Enrique: My eldest great-granddaughter is almost 11.

Amaury: No way!

Enrique: She lives there in Santiago de Cuba.

Amaury: I mean it, you can make anything happen. You

probably did something earlier, but it was in Eduardo Moya’s

Los

Comandos del silencio where I first noticed you. Had you had

any important role before that one?

Enrique: Well, I had been in the learning channel I

mentioned, where Moya directed a few programs.

Amaury: Some of the scenes?

Enrique: Not only that, he would also watched the cast

carefully, and when he was about to start shooting

Los

Comandos… he chose me. It was my first important role.

Amaury: Who else was there? I remember Miguel Navarro.

Enrique: We’re talking about a program made 40 years

ago.

Amaury: Yes, it was a TV show that challenged many

preconceptions.

Enrique: There were Miguel Navarro, Reinaldo Miravalles

and Salvador Wood, who was at the peak of his acting career.

Amaury: That’s right; it sure was a work to remember.

Enrique: It was a top-class gang I truly went out of my

way to learn from, if only by looking at them and watching how they did

their thing.

Amaury: And it was broadcast live, wasn’t it?

Enrique: Totally.

Amaury: I’ve heard that you rehearsed in the halls.

Enrique: Everywhere, even on the rooftop.

Amaury: Anywhere in the building?

Enrique: That’s right, it was something else. We had

seized the ICRT, only coming out of the studio to rehearse the next

take. It really was and aventure for the books. I have fond memories of

when we had finished a scene and were leaving the studio. We would open

the door to the hall outside only to stumble upon the ICRT President,

who was always right there where we worked, day after day and episode

after episode, waiting for the cast to come out to congratulate everyone

on a job well done or make a remark about anything that could be

improved.

Amaury: Wait, wait; bear with me because I’m fascinated

to the point of feeling as if I were hypnotized. I’ve never been

hypnotized, but you make me feel that way. You could tell great

anecdotes about your life as an actor, but I think none is as important

as the story behind your general plastic surgery to play the role of

[Cuban national hero José] Martí, leaving aside the diet you had to go

on. I don’t know anyone anywhere who has done the same, not even in

Hollywood, not for 10 or 15 million dollars. And to cap it all off, they

cancelled the project. Tell me, because I want to hear it from you. You

told me you talked about it on TV before, in a program they made last

year, but you have never told me anything. So let’s hear it, you have me

shaking like jelly here.

Enrique: The idea came from when I had played Lenin on

TV on two occasions, first in

El

Carrillón del Kremlin in 1967, opposite Mario Balmaseda.

Mario did a great job; he was excellent, in all honesty.

Amaury: Yes, Mario is one big name in this field.

Enrique: Five years later I played in a miniseries

directed by Lillian Llerena called

Relatos sobre Lenin, made of five short stories about his

life. I was truly happy with the results. After that the managers asked

Lillian to think about doing a similar thing with five or ten stories

based on Martí’s life and work.

Amaury: For television?

Enrique: Yes.

Amaury: It was like cinema on TV.

Enrique: Exactly. It was about Martí as a child, then as

a teenager, his whole life until he died. Anyway, one fine day Lillian

came to my house and asked Elsa and me to show her our wedding

photographs. We did and she said, “If you lose enough weight to look as

thin as you are in those pictures, I’m sure you can play this role. Of

course, we will have to do something about your nose, make it finer so

that it looks straight with the help of some makeup.” I used to have a

snub nose, like a pitcher. Lillian took me to see Dr. William Gil, who

died last year, and told him what she wanted. Dr. Gil said, “But your

physique doesn’t look in the least like Martí’s!” It was the

understatement of the year.

Amaury: Definitely!

Enrique: He spent like a month going over the idea time

and again, and then one day he called me and said he couldn’t just do my

nose in one go, as he had to change the position of my cartilages first

and wait for about 10 months until they were hard enough for a second

surgery and damn if I know what else. He also told me he had to lift my

eyelids because Martí’s were not as droopy, make my ears stick out like

his and push back my hairline to broaden my brow, but before he could

work on me I had to lose over 40 pounds. And I lost 42 in one month!

Amaury: But that man put your life in danger!

Enrique: No, in fact the doctors looked after me with

great care.

Amaury: I’m sure of that, but you lost too much weight

anyway, more than a pound per day!

Enrique: Well, I went on several diets that were really

hilarious. They’d bring one of those hospital trays with many sections,

and the one in the middle that they usually fill with pea soup only had

a boiled chicken wing. That was lunch, and dinner was the other wing.

Man, the mere sight of those meals was so depressing!

Amaury: So you had a chicken’s two birds every day!

(Laughter)

Enrique: In the bed next to mine was a dystrophic boy,

and you should have seen all the food he would get to eat! He would say,

“Well, don’t you want to play Martí?” Word had spread throughout the

hospital that I was doing just that, so you can imagine. After that came

my seven surgeries, one per every month I spent in the hospital.

Amaury: You were not playing Martí, you were going to be

Martí!

Enrique: And since I was not allowed to get up from bed,

Lillian would be there by my bed every day from 2 to 5 in the afternoon,

reading me things that Martí wrote and articles about him by other

people. Seven months later I was discharged and we started to work

together in her home as I devoted myself to getting inside my

character’s skin.

Amaury: Physically speaking, you were like him by then.

Enrique: Yes, but I still needed the inside part.

Amaury: Of course.

Enrique: Having the physique was not enough; I had to be

able to fill the shoes of the Martí that lives inside every Cuban’s head

and mind, so my character had to be worthy of that image. For that

reason I put my whole heart and soul into the task.

Amaury: You gave yourself entirely to your role?

Enrique: Exactly, because I thought, well, I played

Lenin and now I’ll play Martí, what more could I ask for? But one good

day, after I had spent so much time rehearsing, Lillian and I had a call

from the ICRT, asking us to go there ASAP.

Amaury: Ismael González was the ICRT President at the

time, right?

Enrique: That’s right. We were received in Manelo’s

office, took a sit, and heard what he had to say: “Look, I have nothing

but praise for your effort, but I have to tell you that we’re about to

enter the Special Period and neither the ICRT nor the State can afford

your project.” He was referring to other organizations involved in the

funding.

Amaury: I guess, for it was a big project.

Enrique: It was a huge project. Anyway, Manelo’s point

was that no one had sufficient resources. Well, he himself is my

witness: I simply stood up, turned around and left, tears rolling down

my face. I was so appalled that when I got home I told my wife, that’s

it, I’m quitting, I’ve done enough and decided I’m not going to work

anymore.

From that moment on my wife and my friends were on my back all day long!

One day Eduardo Macías came to visit and told me, “Hey, I know you’re

very downhearted, but I need your help to convince Reinaldo Miravalles

to go with you and Rogelio Blaín and I to the province of Camagüey to

make an adventure story called

Los

Hermanos, and I say ‘convince’ because Miravalles only has

his scenes in the last 30 episodes.” And what do you know, his words

gave me an itch I couldn’t ignore, so we went to see Miravalles toand

talked him into joining us!

Amaury: But tell me something, Enrique, what if you were

the same age now as you were then? Mark my words; I’m not taking you

back to your younger days, I just want to know, if you were young again

today and found another Dr. William Gil –may he rest in peace– as

addicted to Martí, would you do it all over again? Would you make you’re

wife and children go through it all again to play Martí?

Enrique: I believe Fernando Pérez did a beautiful job.

Amaury: That’s exactly what it is, a beautiful piece of

work.

Enrique: May the child and teenager Martí we saw on the

screen bear witness to his achievement. But I think it’s unforgivable

that time keeps passing by and nothing is done about Martí the adult.

Not now that I’m 66, but if I could turn back time and were offered the

part again, I would do it with great pleasure.

Amaury: Enriquito, let’s talk about your landmark

character Silvestre Cañizo in the soap opera

Tierra Brava, inspired by Dora Alonso’s

Media

Luna. How hard was it to the makeup artist and acting

director? Your character is different in the original version.

Enrique: No, that character plays a very minor role in

Media Luna.

Amaury: I know; it was a very small part. I remember

from the script that at some point my mother Consuelito played the girl

Lala in the TV version of

Media

Luna.

Enrique: Dora Alonso sent for me once when the soap

opera was about to end. She was very happy and pleased and congratulated

me on my job, and then she asked me where my character had come from

because it was from her. I told her that wrong though it may be of me to

say so, I had brought it to life myself with [director] Xiomara Blanco’s

consent. I had all the episodes at home, so I knew that in episode 30

the character takes a savage beating and is left to die in the

scrubland. I went to the Orthopedic Hospital and asked a doctor what a

person would look like after such a beating and long time of exposure,

where he’s supposed to get the blows to get such a hump for the rest of

his life, etc., because in the soap opera there’s no hospital to take

care of him. The doctor explained to me how much punishment the

character had to receive to be left as I wanted: “Well, they have to

break your collarbone with a stick or an iron bar,” and so on. Then I

described to Xiomara where the character had to take this and that blow

and be hit with the butt of a rifle to justify his irreversible

deformity. Then I asked a dental technician to design a device or

something that would twist my mouth and make it look as horrible as you

saw.

Amaury: What about your eye?

Enrique: I had to go through five or six tests before

the makeup artists could manage to give me that look. They had tried

many different tricks with a piece of tulle to make it look real but to

no avail, it was plain on camera that it was a fake injury. We didn’t

know what to do, but then I had an idea and told them to use some

mastic, the pastelike cement they use to glue false beards and

moustaches, and directed them to put it here and there on my lid and

wait until it dried to see the effects. They did, and in the end they

all started to jump for joy and cry out, “We did it, we did it!”

However, the process got me a golden staph that took two years to go

away after the soap opera was over.

Amaury: Did you have makeup sessions every day?

Enrique: Every single day, and they had to remove it

with alcohol. It was [actor Enrique] Almirante’s wife Blanca Elena, an

ophthalmologist, who healed me. You have no idea what I went through

with that bug.

Amaury: Nevertheless, you know everybody will always

remember that character.

Enrique: I know. When

En

silencio ha tenido que ser –where I played a Nicaraguan

called Matías– was about to be aired, Edwin Fernández Sr. told me,

“Listen, I’ve been here much longer than you, I have grown old in this

job, and we actors sometimes play characters no one will ever remember,

but others never go away, not even after we’re dead.” And I think he was

absolutely right! Just think how long ago Edwin Fernández left this

world and many of us still refer to him as [the clown]

Trompoloco.

Amaury: You’re right, Trompoloco.

Enrique: That’s what’s happened to me with Silvestre

Cañizo. The soap opera was shown years ago, and anywhere I go in Cuba

between Maisí Point to San Antonio Cape, people call me by the

character’s name, from the street cleaners to the local political

leaders, and that makes me very happy.

Amaury: Enriquito, let’s talk a little about the movies,

where you’ve played many roles. Which one you feel closer to or more at

ease with?

Enrique: Are you talking about my characters in Cuban

films?

Amaury: Yes, of all the films you have ever played in.

Enrique: Playing in movies has been a wonderful

experience to me because of the way filmmakers devote themselves to the

task and the respect they feel for their cast. I have been very lucky to

work with directors who are, in the nicest sense of the word, real

ladies with their actors. I could mention, for instance, Manolito Pérez,

Fernando Pérez, Daniel Díaz Torres...

Amaury: In the film El Benny you worked under

Jorge Luis Sánchez.

Enrique: It was Jorge Luis Sánchez’s first movie, and

that’s something you harbor in your soul. I enjoyed El Benny’s

twofold outcome: the way it appealed to a wide audience –I’ve been

fortunate to star in some box-office hits– and the lessons I learned

from the director, which goes to any other filmmaker.

We had no end of rehearsals with Jorge Luis Sánchez to make that film.

While three of the cast members read their lines to each other across a

table, Jorge Luis would take the fourth chair and watched every one of

us carefully, paying close attention even to where we looked.

Amaury: That’s also part of making a movie.

Enrique: Sure, I know, he would always have his eye on

every detail. That’s how filmmaking works, and I learned many things

that enriched my soul, as I said, because it was an excellent crew.

Amaury: Since the end is drawing near, I’d like you to

tell me: if we were suddenly faced with a natural event that involves

clear and present danger, what would be your advice to the Cuban people?

Enrique: Well, I lived through Hurricane Flora in

Santiago de Cuba, which left me with the shorts and tennis shoes I was

wearing, nothing else. We lost everything, so I had to work and work and

work very hard. And life got us back on our feet thanks to that

struggle…

Amaury: Do you mean a person’s individual effort?

Enrique: Yes. Not the one some people out there call

‘the struggle’, as when they say they’re struggling hard to get on in

life but actually they’re nothing but crooks. That’s not the struggle

I’m talking about. I mean the day-to-day fight and the decision to stand

up to hardship with courage and all that. It was after Hurricane Flora

that I became an actor, so whether it was life’s reward or the result of

my personal effort is anybody’s guess. We live in a country faced with

two kinds of threat: nature’s threat and the other one.

Amaury: That’s where I was going to.

Enrique: But no sweat! Look, I’m so happy to be Cuban

that nothing that happens here scares me in the least. Nothing at all,

be it a hurricane or another Bay of Pigs. I fear nothing because I know

that we’ll eventually come out of whatever happens.

Amaury: One of these days someone who watches Con dos

que se quieran… said that every time I talk about Cuba near the end

of the program I try to make my guests speak about things that neither

they nor I really feel. No one speaks about Cuba as passionately as you

have if they don’t feel it. Thank you very much, Enriquito, I love you

very much.

---ooOoo---

[1] In English, “Three’s a crowd” (T.N.)

[2] Name of the former territory in eastern Cuba presently divided into five provinces. (T.N.)

[3] A well-known promenade in downtown Santiago de Cuba and a very popular hangout with young people (T.N.)

- Cubadebate -

http://www.cubadebate.cu -

Enrique Molina: “La vida nos vuelve a levantar”

Publicado el 28 Diciembre 2010 en Amaury Pérez Vidal, Con 2 que se quieran, Especiales, Noticias

Enrique Molina en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Amaury. Muy buenas noches. Estamos en Con 2 que se quieran, aquí, en el corazón de Centro Habana, en Prado y Trocadero, en los legendarios Estudios de Sonido del ICAIC, en el barrio de Lezama.

Hoy nos acompaña, es un nuevo privilegio para mí, uno de los actores más coherentes, de los actores más brillantes, de los actores más populares. Sencillamente, usando un calificativo que casi nunca uso en la vida, está aquí con nosotros el maravilloso Enrique Molina. Mi socio. Mi amigo querido de los años. ¿Qué te parecen, Enriquito, los programas de entrevistas? ¿Tú crees que tienen alguna utilidad? Ahora hay muchos, no quiero que me hables de este, sería vanidad y petulancia, sino de los programas de entrevistas.

Enrique. Mira, depende, porque yo no sé si será que respondo siempre lo mismo, no tengo otra cosa que contar. O si será que, desgraciadamente, la mayoría de los periodistas que me han hecho entrevistas, todos preguntan lo mismo. Y entonces, cuando me invitaste a venir, yo dije: voy a repetir nuevamente lo que he hablado en otras oportunidades; y uno un poco que ya, no es por mí, sino porque uno tiene el temor de atiborrar a los televidentes de las mismas cosas siempre.

Amaury. Hay muchas preguntas que te voy a hacer que seguramente ya tú has contestado en otras entrevistas, pero hay una generación de gente que cuando te las hicieron en televisión no estaban aquí, o…

Enrique. …O tenían diez años y no les interesaba para nada…

Amaury. …O no les interesaba para nada y ahora, sin embargo, sí. Además, tú sigues haciendo papeles, porque tú no eres un actor que está viviendo del pasado. Ahora, tú naciste en Bauta, vamos a irnos a las cosas esenciales. Bauta, ¿cómo era tú vida en Bauta? ¿Era una vida bonita, o era una vida triste o era una vida pobre, o era una vida alegre? Cómo tú la calificarías.

Enrique. Era una vida bien dura, bien dura. Porque bueno, yo nací en el año 43, te podrás imaginar… los primeros 15 años de mi vida los pasé en Bauta. Con una familia maravillosa, porque mi árbol genealógico se alimenta de las dos razas que tenemos en Cuba: los blancos y los negros. Mi madre y todos sus hermanos, sus padres eran blancos de ojos azules, de ojos verdes. Y la familia de mi padre, mi abuelo, que es el dueño del apellido, Juan Molina, era un poquito más clarito que el traje ese que tienes puesto.

Amaury. (risas) Un poquito nada más.

Enrique. Un poquito más clarito. Yo recuerdo en mi niñez…, mi madre se enfermó de los pulmones cuando yo tenía dos años y entonces los médicos me separaron de mi mamá para que yo no me contagiara. Y a los cuatro años, dos años después de esa separación de mi madre, ella falleció y mi abuela siguió conmigo con un poco de lástima. Yo creo que ella abocó en mí un exceso de cariño. Porque mi padre, a partir del momento en que mi madre se enfermó de los pulmones, se separaron, mi padre fue a hacer otra vida en Camagüey, se casó por allá, qué sé yo. Y mi abuelita me mantuvo ahí, con todo el esfuerzo, con todo el sacrificio que se podía, hasta que ya ella decidió irse a vivir, cuando triunfa la Revolución, en el año 60, ella decide irse a vivir a casa de una hija que tenía en Santiago de Cuba, para descansar un poco de la lucha de la vida que había llevado y me llevó a mí para allá, porque todavía yo era menor de edad y ella sentía todavía gran responsabilidad sobre mí.

Yo tuve una niñez bien dura, porque a los 10 años tuve que dejar la escuela, en cuarto grado; una escuela pública que había en la Calzada de Bauta y dedicarme a hacer un montón de cosas durante el día. Repartir mi horario desde vender aguacates a las 8 de la mañana, con una cesta enorme en la cabeza, que me hundía la cabeza, a las 10 de la mañana dejar los aguacates, los que quedaban, y recoger la bolita, la charada, un listado de la gente que jugaba a la bolita y me buscaba un medio o diez quilos con eso. Por la tarde limpiaba zapatos en el parque de Bauta. Por la noche vendía maní en lo que era el cine Suárez, que ya no existe. Y bueno, y así fue pasando…

Amaury. …Fue pasando tu niñez…

Enrique. …Mi niñez en la lucha esa. Mis primas por otro lado limpiando pisos. Después tuve un tiempo fregando máquinas en un garaje que había ahí en la Calzada de Bauta que se llamaba el Garaje de Lambín, porque así se llamaba el dueño, y en fin, así… Realmente no fui un caso excepcional, aquella era una época bien dura, bien difícil. A mí me tocó vivir esa y la recuerdo porque me ayudó a formarme como persona.

Amaury. ¿Y continuó esa época complicada en los años del principio de la Revolución en Santiago de Cuba o ahí ya la cosa tú sentiste que empezaba a suavizarse para ti?

Enrique. Bueno, allí un amigo, Denis Morales, me consiguió un trabajo en una cafetería que estaba por el Parque Dolores, que se llamaba en aquella época…

Amaury. …Dime más o menos tu edad, para ir llevando…

Enrique. …Yo tenía como 17 años ya en ese momento. Entonces empecé en aquella cafetería a poner en los estuches, en sus cajas correspondientes las botellas de Coca Cola, las de Orange, las de Materva, qué sé yo. Ese era mi trabajo y sacar todas esas cajas para el portal afuera, que el carrero venía a recoger eso. Y ahí empecé a luchar la vida. Ahí me hice ya trabajador oficial, porque ya me reconocieron como trabajador de la cafetería. Ahí tuve mi primera relación matrimonial.

Amaury. ¿Cómo? Estando en la cafetería trabajando, estando de dependiente ahí.

Enrique. De dependiente ahí. Ahí en esa etapa conocí a una mujer que se llama Marta Mestre, con ella tuve tres hijos. Ahí hice mi primera familia. A Santiago de Cuba yo le agradezco, porque mucha gente me ve por la calle y me dice: yo soy coterráneo tuyo, de Santiago de Cuba como tú. Y yo no puedo estarle aclarando a todo el mundo por la calle que yo no soy santiaguero.

Amaury. Claro, pero tampoco hay que estar aclarando eso. Uno es santiaguero porque uno es cubano también.

Enrique. Claro que sí. Yo me siento muy feliz de haber vivido 10 años en Santiago de Cuba y haber comenzado mi vida, ya como hombre, mi vida social y mi vida profesional.

Amaury. Ahí vamos a llegar, ahí vamos a llegar. ¿Tú empezaste en Santiago en el Movimiento de Aficionados, ¿no?, ¿Qué significó para ti el Movimiento de Aficionados? Porque eso es una cosa que está perdida.

Enrique. Está perdida.

Amaury. Perdida, como marchita, ¿no?

Enrique. Perdida.

Amaury. Y tanta gente valiosa que salió de ahí. Tú mismo…

Enrique. Empecé en un grupo de aficionados que había en el sindicato gastronómico de ahí, de Santiago de Cuba. Como la cafetería esa donde yo trabajaba, en el Café Nubiola, ahí, en el Parque Dolores, estaba al doblar de donde estaba la Sala Teatro Profesional de Santiago, el Conjunto Dramático de Oriente. Que era como se llamaba en aquella época. Ahí estaban Félix Pérez, (Raúl) Pomares, Obelia Blanco, todo el grupo, María Eugenia García.

Amaury. Todos esos santiagueros célebres.

Enrique. Ellos iban a la cafetería a merendar y ahí seguimos enriqueciendo la amistad. Hasta que Félix me dice: ¡Oye, dentro de dos o tres días va a salir una convocatoria para el Grupo de Teatro para nuevos ingresos de actores profesionales! Me presenté, me desaprobaron. Esa vez fui junto con Miguel Sanabria, aprobaron a Sanabria, me desaprobaron a mí. Me fui con el moco caído para la cafetería, porque imagínate, yo ganaba 69 pesos, ya tenía el primer hijo. Entonces el Grupo de Teatro pagaba 150 pesos. Yo dije: no, no, yo tengo que comerme a alguien ahí, pero yo tengo que… ¡150 pesos en aquella época!

Amaury. No, no, ¡muchacho!

Enrique. Y a los dos o tres días Félix me volvió a buscar otra vez. Me dijo: Mira, hablé con el argentino. Él sabía que yo…

Amaury. Ah, ¿porque eso quién lo dirigía?, ¿unos argentinos?

Enrique. Adolfo Gutkin y Jaime Swetinzky.

Amaury. ¿Y qué hacían esos argentinos dirigiendo un Conjunto Dramático en Oriente?

Enrique. ¡Tremendos directores!

Amaury. ¿Eran buenos?

Enrique. Tremendos formadores de actores. Y entonces bueno, Félix me dijo: Mira, hablé con el argentino, vuélvete a presentar para ver qué. Y fui y el argentino, Adolfo Gutkin, estaba sentado dentro de una oficina y se me quedó mirando así, ya me había desaprobado y me dice: Mira, ahora tú sales por esa puerta por ahí y entonces dentro de dos o tres minutos entras y lo único que quiero que tú me digas es: Yo quiero ser actor. Es lo único que yo quiero, pero me lo tienes que decir de distintas maneras hasta que yo te pare. ¡Mira, por tu madre!, yo creo que una de las veces me tiré en el piso llorando, me dio como un ataque: ¡¡¡Yo quiero ser actor!!! Otra vez me encaramé arriba del buró y yo creo que los gritos se oyeron en el Parque Céspedes: Que yo quiero ser actor.

Amaury. Yo quiero ser actor, a veces llorabas. (risas)

Enrique. Aquel argentino se reía así mismo como lo estás haciendo tú.

Amaury. Claro, yo te imagino diciendo: Yo quiero ser actor, de distintas maneras.

Enrique. Este hombre está loco o qué le pasa. Hasta que me dice: Mira, tú vas a ser actor. Ya, llegué a la cafetería y digo: ¡Pedro Carrió, yo soy actor! ¿Cómo? Yo quiero. Yo soy actor, ya, de ahí del Conjunto Dramático de Oriente, yo soy de allá. Me voy de la cafetería y no trabajo más. Y de ahí para adelante, bueno, la primera noche, imagínate tú, una reunión con los argentinos y todos los actores, hablando de Stanislavky, de Grotowski, de Brecht toda esa gente. ¡De qué hablan!, me dieron ganas de bajar la escalera corriendo. ¿Dónde me he metido yo? y de ahí, Amaury, mira, a golpe de…

Amaury. A golpe de talento, mi socio.

Enrique. A golpe de luchar y de batallar.

Amaury. De talento que como tú hay muy poquitos que tienen ese talento. ¿Y en Santiago hiciste radio?

Enrique. Sí, hice radio en la CMKC, pero soy muy malo en la radio.

Amaury. ¿Sí?

Enrique. Oh, horrible.

Amaury. Tú no puedes ser malo en nada, Enrique.

Enrique. No, no, malísimo soy, porque mira, para mí el medio más difícil que hay en la actuación es la radio. Yo admiro muchísimo a esos actores que cogen un libreto y a primera vista empiezan ya a interpretar, a actuar con eso que está escrito ahí. Yo…, eso es muy difícil, yo no estoy preparado para eso. Yo estoy preparado para aprenderme en mi tiempo, el que yo le doy, memorizar, estudiar la situación del personaje que voy a interpretar.

Amaury. Las líneas.

Enrique. Qué sé yo, ya cuando yo tengo el dominio, más o menos, de ese texto que está ahí, vamos para allá.

Amaury. ¿Tú te aprendes también el texto del otro actor que se relaciona contigo o solamente el pie que te da?

Enrique. No, no, tú tienes que estudiártelo todo, por lo menos yo me lo estudio.

Amaury. Porque hay gente que nada más se estudia el pie del que viene.

Enrique. No, no, no, eso…, esos son los actores que tú ves que están como pescado en nevera. Que el otro está hablando y él está pensando nada más que el otro diga: papa, cuando diga papa, hablo yo, están muertos ahí. No, no, no, yo no puedo hacer eso. Yo tengo que incluso estudiar la psicología del personaje con el que estoy dialogando yo, no solamente el mío. Porque ¿cómo tú puedes establecer una relación?…

Amaury. Y una cosa, Molina, en esa relación, ¿Quién marca el tono en un diálogo?…, por ejemplo: entre tú y yo, ¿quién va a marcar el tono, el tono en el que hablamos?

Enrique. Tú empezaste en un tono haciendo la entrevista y en el tono tuyo continúo yo. Yo, puede ser que en lo que voy a hablar, puedo subir un poquito más el tono porque estoy bravo, porque no sé qué.

Amaury. No, no te pongas bravo. (risas)

Enrique. No, no, yo no me pongo bravo, pero siempre uno va al tono con el que está…

Amaury. …Al tono con el que yo te voy llevando.

Enrique. Claro.

Amaury. Y si yo voy levantando el tono o lo subo un poco más porque me parece que hay que ser un poquito más enfático en algo, tú te vas conmigo.

Enrique. En este caso, sí. Aquí, aquí. En la actuación, no, porque a lo mejor tú estás interpretando un personaje que te pegas al pecho del berrinche que tienes.

Amaury. Un histérico loco.

Enrique. Y el mío está muerto de risa, tranquilo.

Amaury. Te lo preguntaba, porque para un músico el asunto de las tonalidades es muy importante. ¿Cuánto vienes para La Habana y por qué vienes para acá? Ya tenías allá una esposa y tenías unos muchachos y todo. ¿Con todo el mundo arrancaste para acá?

Enrique. Ah, bueno. La vida se me fue complicando, esto es algo bien íntimo, pero no sé, aquí uno viene a tu programa como a confesarse.

Amaury. No digas eso, no digas eso.

Enrique. Por lo menos es lo que he sentido. A mí me gustaron muchísimo las cosas tan lindas, tan íntimas, que dijo Frank Fernández.

Amaury. Es que la gente cuenta cosas.

Enrique. Tan humanas.

Amaury. Yo me siento privilegiado por eso.

Enrique. Sí, cosas preciosas de la vida de él personal, qué sé yo. Y entonces, bueno, mira, cuando yo… mientras yo trabajaba en la cafetería, la relación mía matrimonial iba perfecta; pero cuando empecé a ser actor, que ya yo bajaba por Enramada.

Amaury. Calle maravillosa.

Enrique. Además, yo tenía 17, 18 años ¿tú me entiendes? Estaba precioso, yo tuve belleza.

Amaury. Tú eres muy lindo, chico.

Enrique. Entonces, mi hermano, ya eso, ya ahí empezó como que ha resquebrajarse la relación matrimonial, ya había cosas que no se entendían, que por qué yo tenía que pasarme tantas horas en un ensayo. Ya las mujeres me saludaban por la calle y querían retratarse con el actor que trabajaba en una obra de teatro. Esas cosas que ocurren en la vida nuestra. Hasta que llegó un momento en que ya aquello no dio más y yo tuve que decidir romper aquella relación. Vine a La Habana en el año 70. A los pocos días de estar aquí empezó mi nueva relación, con la mujer que todavía sigue siendo mi esposa.

Amaury. Que ya cumplieron 40 años de estar juntos.

Enrique. Anjá, ya cumplí los 40 años de casado, que ha significado mucho para mí, mucho, mucho, mucho. Yo vine de Santiago de Cuba con un maletín en el que traía dos pantalones y tres camisas y 28 pesos en el bolsillo, no tenía nada más que eso. Vine con una carta de Enrique Bonne, que hacía constar que yo era actor.

Amaury. ¿Enrique Bonne, el músico?

Enrique. Enrique Bonne, el músico, que era jefe de programación de Tele Rebelde en Santiago de Cuba. Yo fundé Tele Rebelde. Del teatro pasé a la televisión allá en Santiago y él me dio una carta que decía: Enrique Molina, actor de aquí, qué sé yo. Me dijo, bueno, con eso ve para La Habana a ver qué tú puedes resolver. Vine para aquí y estaba yo parado frente a la cafetería que en ese momento estaba frente a la escalinatica del ICRT, y estoy conversando ahí con Carlos Quinta, para que él me alumbrara de cómo era la cosa aquí en La Habana y me dice: mira, ese que viene bajando por ahí es el director general de la televisión, Abraham Masiques. Agarré mi maletín, crucé la calle y dígole: mire, usted me disculpa, yo traigo una carta aquí de Enrique Bonne, que dice que yo soy actor de Santiago de Cuba y vengo a ver si me pueden dar trabajo aquí. Se me quedó mirando así. Ahí está él, que no me dejará mentir nunca.

Amaury. Él no deja mentir a nadie, así que no te preocupes.

Enrique. Agarró mi maletín, viró para atrás, me dice: sigue detrás de mí, pro, pro, pro, cogió el elevador. Ahí cogió por todo el pasillo, cogió el otro elevador hasta el 9no. piso. Me llevó a ver a uno que se llamaba Carlos Díaz, que era el que repartía el talento cuando venía un director a pedir actores y actrices, y pra, pra, le dijo a Carlos Díaz: A partir de mañana me le das programas ya, en las teleclases que se están haciendo aquí a las 7 de la mañana. Y ahí empecé.

Amaury. Rapidísimo.

Enrique. Me dijo: ¿Tú no tienes dónde vivir? Dígole: bueno, tengo la familia mía en Bauta. Me dijo: mira, esta llave es de una casa de visita que está en muy mal estado en la calle Neptuno, allí hay un cuarto que tiene como cuatro o cinco camas, yo creo que hay una cama vacía, por lo menos para que no duermas en la calle. Toma. Yo me quedé así que no entendía nada… Es de esas cosas de la vida de las cuales yo siempre me he sentido muy feliz, de la suerte, de la luz, de no sé qué.

Amaury. ¿Pero no habías conocido a Elsa todavía en ese momento?

Enrique. Sí, ya la conocía. Y ahí me quedé y a los seis meses me casé con Elsa Ruiz y ya, 40 años y dos hijos maravillosos que tengo con ella.

Amaury. Tienes hijos…

Enrique. …Mis hijos de Santiago.

Amaury. Tienes hijos, pero tienes nietos, y tienes bisnietos.

Enrique. Tengo tres bisnietas.

Amaury. Es que esto no se puede creer, bueno, claro, es que empezaste muy temprano.

Enrique. Muy tempranito y mis hijos también empezaron temprano.

Amaury. No, hombre… con esa escuela del padre, que a los 17 años ya tenía dos hijos.

Enrique. La bisnieta mayor va a cumplir 11 años.

Amaury. No puede ser.

Enrique. En Santiago de Cuba, bisnieta.

Amaury. Es que contigo cualquier cosa puede ser. Bueno, debes haber hecho algo antes, pero cuando yo me fijé por primera vez en ti, fue en Los Comandos del silencio, de Eduardo Moya. ¿Habías hecho algo antes en TV importante?

Enrique. Bueno, había hecho las Teleclases que te hablé. Moya dirigía algunas.

Amaury. Algunas de las escenas de las teleclases.

Enrique. De esas escenas y él, bueno, fue mirando a los actores y cuando fue a hacer Los Comandos del Silencio, me llamó. Esa fue mi primera gran posibilidad.

Amaury. ¿Estaban quiénes? Miguel Navarro estaba.

Enrique. Estamos hablando de hace 40 años atrás.

Amaury. Sí, sí, esa fue una serie que rompió todos los esquemas.

Enrique. Salvador Word estaba en su apogeo como actor, Miguel Navarro, Reinaldo Miravalles.

Amaury. Sí, sí, es que aquello no tenía nombre.

Enrique. El piquete de gente era… yo hice todo lo posible, no escatimé un minuto para absorberles todos sus conocimientos. Verlos nada más, cómo hacían ellos las cosas.

Amaury. ¿Y en vivo era, no?

Enrique. En vivo, esa aventura la hicimos en vivo.

Amaury. Cuentan que se hacían cosas en los pasillos.

Enrique. En todos lados, en la azotea.

Amaury. En todo el edificio.

Enrique. En el edificio del ICRT, no, no, terrible… tomábamos el ICRT, nos salíamos del estudio para hacer escenas. Aquello fue una aventura realmente histórica… Y tenía, yo recuerdo de aquella época, algo bien bonito. Cuando ya daban el corte, que ya se acababa el programa que íbamos a salir del estudio, al abrir la puerta al pasillo, el presidente el organismo estaba ahí, en el taller, en el lugar de trabajo con la gente ahí, para felicitarnos por el capítulo, o para hacernos alguna observación de algo que no había salido bien, alguna cosa. Día por día y capítulo tras capítulo.

Amaury. A ver, a ver, yo estoy tratando, porque estoy tan fascinado, me tienes como hipnotizado. A mí nunca me han hipnotizado, tú me tienes hipnotizado.

Tú tienes anécdotas en tu vida artística tremendas, pero yo creo que ninguna es tan importante como el hecho de que tú hayas sido capaz de someterte a una cirugía plástica general para hacer el papel de Martí. Aparte de someterte a una dieta. Yo no conozco a nadie que haya hecho eso en ninguna parte, ni en Hollywood, ni por 10 millones, ni por 15. Pero después, además, esa película no se hace. Cuéntame, porque yo quiero oírlo de tu boca. Ya sé que a lo mejor lo has contado alguna vez en un programa, me dijiste que hace poco, el año pasado, bueno, pero a mí no me lo has contado nunca. Cuéntamelo ahora mismo, yo estoy temblando con eso.

Enrique. No, esa idea surge cuando yo interpreté a Lenin, o sea, yo interpreté a Lenin en dos oportunidades. Primero en el año 67, El Carrillón del Kremlin, que yo lo hice en la televisión y Mario.

Amaury. Mario Balmaseda.

Enrique. Mario hizo un trabajo, excelente el trabajo de Mario, excelente, dicho con toda…

Amaury. Sí, sí, es que Mario es otro de los grandes.

Enrique. Cinco años después, yo hice una miniserie que se llamaba Relatos sobre Lenin. Eran cinco cuentos sobre la vida de Lenin. Se terminaron y quedaron…, de verdad que yo quedé satisfecho con ese trabajo. Lo dirigió Lillian Llerena. Y a raíz de esos cuentos, la televisión, el organismo le plantea a Lillian la posibilidad de hacer eso mismo: cinco o diez relatos sobre la vida y obra de Martí.

Amaury. ¿Era en televisión?

Enrique. Para la televisión.

Amaury. Era para la televisión. Era cine en televisión.

Enrique. Anja. Martí niño; Martí adolescente; Martí todo, hasta que muere Martí. Y un buen día se me aparece Lillian en la casa y me dice: Déjame ver al álbum tuyo de bodas con Elsita. Se lo enseñamos, y empezó: Si tú te vuelves a poner así flaquito, como estabas en esta foto, yo creo que tú me puedes hacer el personaje. Siempre hay que operarte la nariz, porque yo tenía antes una nariz cuadrada, que parecía un porrón de tomar agua, y entonces, hay que operarte la nariz, porque con esa nariz, hay que afinártela para que después con el maquillaje se te haga recto, qué sé yo. Y Lillian y yo nos fuimos a ver al Doctor William Gil -ya falleció el año pasado- y le dimos la idea a William Gil. Y él me dijo: pero es que tú físicamente no tienes nada que ver con Martí. Claro, que iba a tener yo que ver con Martí.

Amaury. No, claro.

Enrique. Y él se pasó como un mes estudiando aquello hasta que me llamó y me dijo: Oye, yo no te puedo operar la nariz ahora así de un viaje. Te la tengo que operar en dos partes. Tengo que virarte los cartílagos, mantenerte ahí como 10 meses con los cartílagos invertidos para que se endurezcan y después volvértelos a poner como eran, qué sé yo. Pero, mira, tengo que operarte los párpados, porque Martí era de ojos abiertos; tengo que separarte las orejas, porque Martí era de orejas separadas; tengo que correrte el nacimiento del pelo hacia atrás, porque Martí, mira como tenía las entradas. Tengo que quitarte todo lo que te va a sobrar cuando tú ya termines de bajar las cuarenta y pico de libras. Y en un mes, ¡en un mes!, bajé 42 libras.

Amaury. Pero es que ese hombre puso en riesgo tu vida.

Enrique. No, pero la verdad que yo tenía una atención médica ahí extraordinaria, extraordinaria.

Amaury. No, eso no lo dudo, pero son muchas libras, porque es más de una libra diaria.

Enrique. Entonces, tenía unas dietas que eran comiquísimas. Era una bandeja, de esas de las bandejas de los hospitales, que tiene muchos departamentos y me traían en el centro, en el medio, donde va el potaje, ahí me traían un ala de pollo hervida sin sal. Ese era mi almuerzo y por la tarde, la otra ala, la derecha, así. Cuando yo veía aquello…

Amaury. Te traían de un pájaro las dos alas. (risas)

Enrique. Entonces ahí estaba ingresado conmigo, al lado, un muchachito que era distrófico y lo que le llevaban de comida a aquel muchacho, era para… imagínate, distrófico. Y entonces el muchacho me decía: ¿Tú no quieres hacer Martí? Porque se corrió en todo el hospital que yo iba a interpretar a Martí. Imagínate tú. Bueno, entonces viene el proceso de las operaciones y fueron en total 7 cirugías, que fueron los siete meses que estuve hospitalizado.

Amaury. Tú no ibas a hacer el papel de Martí, ibas a ser Martí. Te querían convertir en Martí.

Enrique. Y con Lillian Llerena todas las tardes sentada al lado de mi cama, ahí, porque no me dejaban caminar, ahí, leyéndome cosas de Martí. Todas las tardes iba para allá a las dos y hasta las cinco de la tarde. La obra de Martí y los que hablaban sobre Martí, cómo era Martí. Salí del hospital a los siete meses y empecé a trabajar con Lillian en su casa y a buscar en actuación a ese Martí.

Amaury. Que ya físicamente lo tenías.

Enrique. Claro, pero hacía falta el de aquí adentro.

Amaury. Claro.

Enrique. Porque no hacía falta solamente el físico. Era ese hombre que fuera capaz de convencer al Martí que cada uno de nosotros tiene en su cabeza. Cada cubano tiene un Martí aquí en su imaginación y había que hacer un Martí que fuera, que fuera digno. Yo le entregué a aquello el amor, la vida, el corazón.

Amaury. Le entregaste la piel.

Enrique. Porque yo me decía: después que ya yo hice Lenin, hacer Martí ahora, ya, qué más puedo pedir como actor. ¡Qué más puedo pedir! Y un buen día, después de muchísimo tiempo ensayando, nos llaman del ICRT, a Lillian y a mí, por favor, que vengan urgente a la oficina de Manelo.

Amaury. Sí, que entonces era el Presidente del ICRT, Ismael González.

Enrique. El presidente del ICRT. Y vamos para la oficina de Manelo y nos dice. Lillian, por favor, siéntese ahí. Molina, siéntate aquí. Miren, yo no sé lo que yo haría por reconocer el esfuerzo que tú has hecho, pero te tengo que decir, que va a comenzar en estos días, ya, el Período Especial, y ni el organismo, ni el Estado -no era solamente el ICRT, habían otros organismos que iban a colaborar en la construcción de…

Amaury. Sí, claro, una cosa como esa.

Enrique. Era un proyecto gigantesco del ICRT. Nadie puede apoyar esto, ni el Estado, ni nadie, no hay con qué. Me levanté de aquella butaca, mira, no, no. Ahí está Manelo que no me dejará mentir. Yo no dije nada, me paré, así, tranquilamente, viré la espalda y me fui. Las lágrimas me corrían a chorros por toda la calle. Yo, en mi mundo, en mi enajenación le dije a mi mujer cuando llegué a la casa: voy a renunciar, yo no voy a trabajar más. Yo creo que ya he hecho bastante con mi trabajo, y no voy a trabajar más.

Mi mujer me cayó ahí, los amigos me cayeron ahí y un día se me apareció Eduardo Macías en la casa, y me dice: oye, yo sé que tú estás mal de ánimos, pero te vengo a buscar para que me ayudes. Entre tú y yo vamos a convencer a Reinaldo Miravalles para que tú y él se vayan con (Rogelio) Blaín, y conmigo para Camagüey para hacer una aventura que se llama Los Hermanos y quiero convencer a Miravalles porque él nada más que trabaja en los últimos 30 capítulos. Y mira, aquello me empezó otra vez a mover esa cosa que uno no puede negarse a eso ¿verdad? Y me fui con Macías a casa de Miravalles y lo convencimos y se fue el viejo para allá con nosotros.

Amaury. Pero ven acá, Enrique, si tú tuvieras ahora la misma edad que tenías en aquel momento. Hoy, fíjate, hoy. No es que te ubiques en el ayer. No es que te ubiques en el joven que fuiste, sino en el joven que podrías ser hoy y te encontraras a otro delirante martiano, como el Doctor William Gil -que en paz descanse-. ¿Tú te someterías a eso? ¿Someterías a tu mujer, someterías a tus hijos nuevamente a ese proceso, para hacer Martí?…

Enrique. Yo creo que esto que hizo…

Amaury. Fernando Pérez.

Enrique. Fernando Pérez, es una belleza.

Amaury. Es que es una belleza.

Enrique. Para aplaudírselo, ahí están, en la pantalla, el Martí niño y el Martí adolescente. Pero ese Martí adulto, yo creo que es imperdonable que sigan pasando los años y que no se haga. Si yo me viera otra vez, no ahora con las condiciones físicas que tengo, porque ya tengo 66 años, pero si echamos el tiempo atrás y me vuelven a plantear lo mismo, yo lo vuelvo a hacer, pero con una satisfacción tremenda.

Amaury. Enriquito, hablemos de este personaje icónico tuyo, Silvestre Cañizo, de la telenovela Tierra Brava, inspirado en Media Luna, de Dora Alonso, ¿cómo fue ese problema de maquillar a ese hombre? ¿Cómo fue crearlo? Ese personaje no está concebido de esa manera en la novela.

Enrique. No, no, en la novela el personaje prácticamente ni existe.

Amaury. No, era un personajito, yo recuerdo en los libretos que mi mamá, Consuelito, hizo en algún momento de la niña Lala, cuando hicieron Media Luna.

Enrique. Sí. Bueno, una vez me mandó a buscar Dora Alonso, ya cuando la novela estaba casi en su final, y ella, muy contenta, muy satisfecha, muy feliz, me felicitó y me dijo: Mira, ese personaje yo no lo creé. ¿Quién creó ese personaje? Dígole: mire, Dora, esto, el personaje, aunque me sea feo decirlo, y con la anuencia de la directora, de Xiomara Blanco, lo fui creando yo. Lo creé, porque lo primero que hice fue que me fui, como ya yo tenía los capítulos en mi casa, todos, y ya yo sabía que a partir del capítulo 30 al personaje le daban aquella paliza que lo dejaban botado en el monte. Yo me fui a ver a un médico, allí al Hospital Ortopédico, a consultar con él como quedaría una persona que recibe una paliza de esa manera, que se queda abandonado, silvestre, en el monte, ¿Por dónde hay que darle para que se justifique que esa joroba queda para toda la vida? Porque no había un hospital (en la novela) no hay nada. Y entonces él me fue explicando que para lograr… Yo sí le hice al médico, físicamente, lo que yo quería, cómo yo quería quedar. Y me dijo: bueno, mira, hay que partirle la clavícula al personaje con algo, con un palo, con un pedazo de hierro, con algo y entonces así lo hicimos. Después le expliqué a Xiomara por dónde es que se asalta al personaje, que se vea un culatazo que le dan con un fusil, dónde le dan, para justificar esa lesión que se le queda para toda la vida. Después me fui a ver a un técnico de prótesis bucal para que me creara esa cosa que se levantaba aquí por dentro; él me creó una pieza que yo me ponía por allá adentro, y se quedaba la boca virada, horrible.

Amaury. ¿Y lo del ojo?

Enrique. Y entonces, con las maquillistas hice como cinco o seis pruebas de maquillaje para lograr el efecto ese del ojo horrible. Y nada, con un pedacito de tul, hicieron muchísimas pruebas y ninguna dio resultado, porque me iba al estudio con la cámara, para ver cómo se veía y se veía que era falso. No teníamos con qué hacer eso. Y a mí se me ocurrió decirle a la maquillista: mira, vamos a coger un poco de mastic, que es con lo que se pegan las barbas y los bigotes de los personajes. Bájame aquí el párpado, échame mastic aquí, súbeme esta parte de aquí y échame por aquí arriba. Aguántamelo un rato ahí y después suéltalo a ver qué pasa. Así lo hicimos y la maquillista dio gritos de alegría. Ahhh, lo logramos, lo logramos. Pero eso me costó a mí un estafilococo dorado que me duró dos años, después que se terminó la novela.

Amaury. Sí, claro, porque eso te lo hacían todos los días.

Enrique. Todos los días y todos los días me lo tenían que quitar con alcohol, un chorro de alcohol ahí para que eso se despegara. Eso era diario. Y entonces la esposa de Almirante, Blanca Elena, fue la que, ahí, ahí.

Amaury. La doctora.

Enrique. La doctora, oftalmóloga, me curo el estafilococo ese. Pero pasé una…, terrible

Amaury. De todas maneras todo el mundo…, tú sabes que para siempre te van a recordar por ese personaje.

Enrique. Sí, es un personaje que, una vez Edwin Fernández, padre, me dijo, a raíz de salir al aire En silencio ha tenido que ser, que yo hacía el nicaragüense aquel, Matías.

Amaury. Cómo no.

Enrique. Y una vez me intercepta en el camino y me dice: Oye, yo llevo mucho más años que tú en la carrera esta, ya estoy viejo de actuar, y los actores tenemos personajes por los que nadie nos recuerda, pero tenemos otros personajes que quedan para el resto de la vida, aún después de muertos. Y creo que tenía absoluta razón, porque mira cuántos años hace que Edwin Fernández ya no está con nosotros y todavía cuando vamos a hablar de Edwin Fernández, decimos Trompoloco.

Amaury. Trompoloco, claro, claro.

Enrique. Y con Silvestre Cañizo me ha pasado eso. Hace años ya de la novela y yo ando por toda Cuba, desde la Punta de Maisí al Cabo de San Antonio y todo el mundo me llama Silvestre Cañizo, todo el mundo. Desde el que recoge la basura, hasta el nivel más alto que haya en el país, Silvestre Cañizo, y yo me siento feliz con eso.

Amaury. Enriquito, ¿por qué no hablamos un poquito del cine? Tú has hecho muchos papeles. ¿Con cuál te sientes más identificado? ¿Con cuál te sientes más cómodo, cuando los recuerdas?

Enrique. ¿Pero te estás refiriendo a…?

Amaury. A todo el cine que has hecho a lo largo de tu vida.

Enrique. Mira, el cine para mí ha sido una experiencia maravillosa por el rigor y por el respeto que los directores de cine tienen con sus artistas. Y he tenido la suerte, realmente, de trabajar con directores de cine que son, dicho en el buen sentido de la palabra, damas, dirigiendo a los actores. Como es el caso de Manolito Pérez, como es el caso de Fernando Pérez, Daniel Díaz Torres.

Amaury. En la película del Benny, que trabajaste con Jorge Luis Sánchez.

Enrique. Jorge Luis Sánchez, su primera película. Y uno se queda con eso en el alma. Es el espíritu de dos resultados, que es lo que disfruta uno; el resultado de la película, el resultado final con el público y he tenido la suerte de hacer algunas películas que han tenido un impacto importante en la población. Y lo que te deja, la enseñanza que te deja cada uno de esos directores.

Mira, con Jorge Luis Sánchez, mira que ensayamos con Jorge Luis en la película del Benny. Y Jorge Luis se paraba así, los tres actores, por ejemplo, que estábamos en un diálogo en una mesa, él se sentaba frente, ocupando el cuarto puesto de la mesa, a mirarnos las caras a cada uno, en detalle, de los diálogos que estábamos ensayando, y estaba pendiente hasta de la mirada.

Amaury. Claro, eso también es el cine.

Enrique. Claro, claro, pero en detalle, ahí, todo el detalle, con mucho rigor. Y así se trabaja el cine. Ahí he aprendido mucho. Me he alimentado el alma, como te decía, de esta gente, de ese colectivo buenísimo, buenísimo.

Amaury. Bueno, me estoy acercando al final. Si estuviéramos en una situación de repente de peligro inminente, ante una cosa natural, una cosa provocada por fuerzas internas. ¿Cuál sería el consejo que tú le darías a los cubanos ante cualquier eventualidad que nosotros sintiéramos?

Enrique. Bueno, yo viví en carne propia el ciclón Flora, allá en Santiago de Cuba y yo me quedé con un short que tenía puesto y un par de tenis, más nada. Nos quedamos sin nada y empecé a luchar, y a luchar, y a luchar. Y la vida nos volvió a levantar y la lucha…, la lucha, esa…

Amaury. La lucha interior, la individual.

Enrique. Esa. No lo que se dice por ahí: estoy luchando y son unos bandidos. A esa lucha yo no me refiero. Me refiero a la lucha de la vida, de enfrentar la vida con valor, con firmeza, qué sé yo… y nos volvió a levantar. Y después de eso fue que me hice actor, después del ciclón Flora. Mira tú si la vida, yo no sé si la vida me premió o fue producto de ese esfuerzo. Nosotros vivimos en un país que está constantemente amenazado por dos vías: la natural y la otra.

Amaury. Ahí iba.

Enrique. Eh, y nada. Mira, yo me siento tan feliz de ser cubano, que a mí nada de lo que ocurra en este país me asusta ni me da miedo. Nada, nada. Lo mismo un ciclón como si se vuelve a repetir otra vez Playa Girón. No, nada me asusta, porque sé que de ahí uno va a salir.

Amaury. El otro día una persona que ve el programa, un televidente o una televidente del programa, decía que yo, cuando hablaba de Cuba en los finales de los programas trataba de poner en boca de los invitados cosas que en realidad yo no sentía, ni sentían ustedes. Nadie habla de Cuba con esa pasión con la que tú has hablado si no es porque lo siente. Muchas gracias, Erniquito. Te quiero mucho.

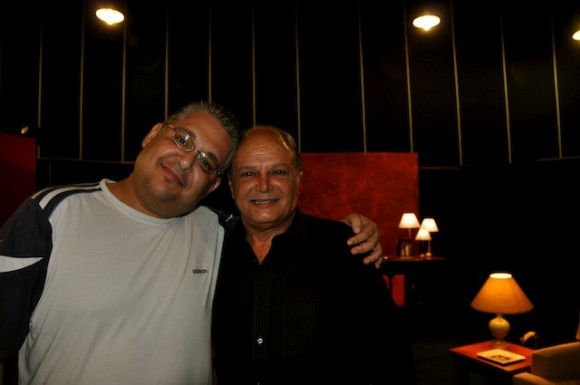

Enrique Molina y Amaury Pérez en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Enrique Molina en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Enrique Molina en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Enrique Molina y Amaury Pérez en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Enrique Molina y Amaury Pérez en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Rafael Solís, Enrique Molina y Amaury Pérez en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

Manolito Iglesias, editor del programa y Enrique Molina en "Con 2 que se quieran". Foto: Petí

URL del artículo :

http://www.cubadebate.cu/noticias/2010/12/28/enrique-molina-la-vida-nos-vuelve-a-levantar/

Clic aquí para imprimir.

Cubadebate, Contra el

Terrorismo Mediático

http://www.cubadebate.cu