Revolution and Culture

Revolution and Culture

No. 6 September-October 2008

A dream in Isfahan

By

Margarita Mateo

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Rather than a dream, it was like entering a dimension where every object

spoke a language that humans can understand, each word gradually

becoming visible in clear-cut shapes with shadows of their own as I held

forth about Latin American and Caribbean myths in the lecture hall of

the University of Tehran. The first word that came into existence was a

quetzal’s feather that popped out of an Aztec verse and started to float

over the audience. Then came the blowpipes of the Maya twins, the

Quechua princess’s singsong and Sister Juana’s god of the seeds, and

each and every word, transmuted into images, would levitate briefly just

before vanishing into thin air.

After my presentation I met with my teachers, already dead or still

alive: Graziella, who spoke in other people’s language, and Ofelia, who

lay on a bed, a veil drawn over her head, beside an elderly Persian lady

with penetrating eyes no less intent on teaching me a lesson. It’s a

spirit, I thought, whose gaze I’d better not hold for so long. So I

looked away at once and closed my eyes, but no sooner had I opened them

again and got ready to receive the manuscripts that I never really

managed to have in my hands than I woke up. That my dream had been set

in Isfahan, a jewel of the Middle East located right in the middle of

the world, seems highly revealing. Of what, I don’t really know. But

since I have grown to learn that striving to make out a sign that

refuses to be deciphered could earn us a one-way ticket to insanity, I

stop trying to figure it out. I know there’s something, but I just let

it go: hands off.

Isfahan is an oasis in mid desert. A journey through rocky mountains

spreading out for miles on end alongside an arid, desolate plain with

barely any sign of life leads to this lively city where there’s a

continual coming and going of people on tree-lined avenues and streets

named after poets, all dotted with fountains of crystal-clear water in a

real display of humidity that defies the parched desert and dry climate

by imposing greenness on the ocher-colored landscape.

The palace of Chehel Sotoun (or Forty Columns) is considered one of the

finest examples of Persian architecture. Its majestic portico, where

foreign ambassadors used to be welcomed, opens to an entrance hall still

decked with mirrors and shiny metal plates that produce a stunning,

almost blinding glare. Time, however, has worn out the once-splendid

columns that seem to rise almost out of sight to support the vast

pavilion. Right in the center of this huge chamber is a square fountain

with a lion in each corner whose droopy, almond-shaped eyes look almost

imploring, their jaws wide open in a sort of grimace that resembles more

an eternal yawn forever imprinted on the timelessness of the stone than

the defiant roar they surely intend to make, giving away instead a fixed

expression that jumps out at the visitors and urges them to pat the

animals on the head or stroke their seemingly plaintive snouts, out of

compassion toward their frozen helplessness. It all reminds me of a

Persian poem by Hamid Mosadegh that I read last night in my room: “Stone

lion, puzzled in the dust, your dignity now forgotten”.

But if you double-check the place, you will see there are only twenty

columns, not forty. The rest of them are just a reflection in the water

of the fountains. Yet, the name of the palace makes no distinction

between the solid ones bearing the weight of the portico and the

reflected ones, which are but a shimmering illusion. They are now bare

of the coating that matched the semidome’s back in their heyday, when

sets of mirrors arranged on their shiny surface reflected light and

brightness to no end. Again, the name of the palace stems from Persia’s

view of the world, so prone to fantasy, unreal realms and different

dimensions, as evidenced by the refined sensibility noticed in its

people’s customs.

Our long way to Isfahan started in Quom, the religious city where for

many years the mullahs get a higher education and devote

themselves to their rituals before they can wear a turban of a color

befitting their rank. Then we arrived in Kashan, oppressively hot under

a scorching sun and home to black legends, poisonous spiders and the

Garden of Fin, the first place we visited, where, as if to confirm the

aura of darkness that surrounds the city, a shah killed his Prime

Minister, a much-loved and respected man. A terrible, everlasting

feeling of gloom seems to hang in the air of the complicated labyrinth

of baths where the crime took place as its low ceilings, narrow halls,

winding passageways and sinister twists and turns brings back memories

of the tragedy caused by the murderous king.

I entered the Ameriha House, my body hidden underneath a chador

and resigned to the ravages of the blistering heat, and the coolness

inside brought instant relief. It’s a really intense sensation that

makes you grateful for latticework, shady spots and whatever keeps you

away from the hard, merciless weather outside. Probably the old female

dwellers of this house, who could get rid of their robes as soon as they

were indoors, were in a far better position to feel such a sudden change

of temperature, but to a body like mine, used to fighting the tropical

heat with nudity, fans and the moves you need to make –take off, open

up, blow on, move out– the torrid Persian sun, as well as people’s

stance on its effects, are a whole new experience. With its more or less

frenzied motion, a fan is also a sign of despair and dissatisfaction

with the climate. Except that in Iran those are unnecessary gestures:

you can’t take off your veil, so there’s no point in wishing for a cool

breeze when you must wage such a deaf, mute, invisible struggle

underneath your robe. Any action otherwise seen as a sign of your body’s

rebellion against the overwhelmingly suffocating heat would have been

not only unforgivably tactless to my hosts, but totally useless at that.

These women wage such fights quietly, with a sense of pride and dignity

that goes beyond pure resignation.

In such circumstances, the house’s ventilation system –shady halls

through which the breeze flows after being caught in the tall minarets

and cooled down by indoor fountains– prove to be a remarkable discovery.

Thus the fresh air sneaks in every room via holes cleverly concealed by

the wall design. I felt a great sense of relief when Mohammed led me to

the base of the tower that fed the Ameriha House, and again later in the

Buwayhid mansion and the Sultan’s Bathhouse.

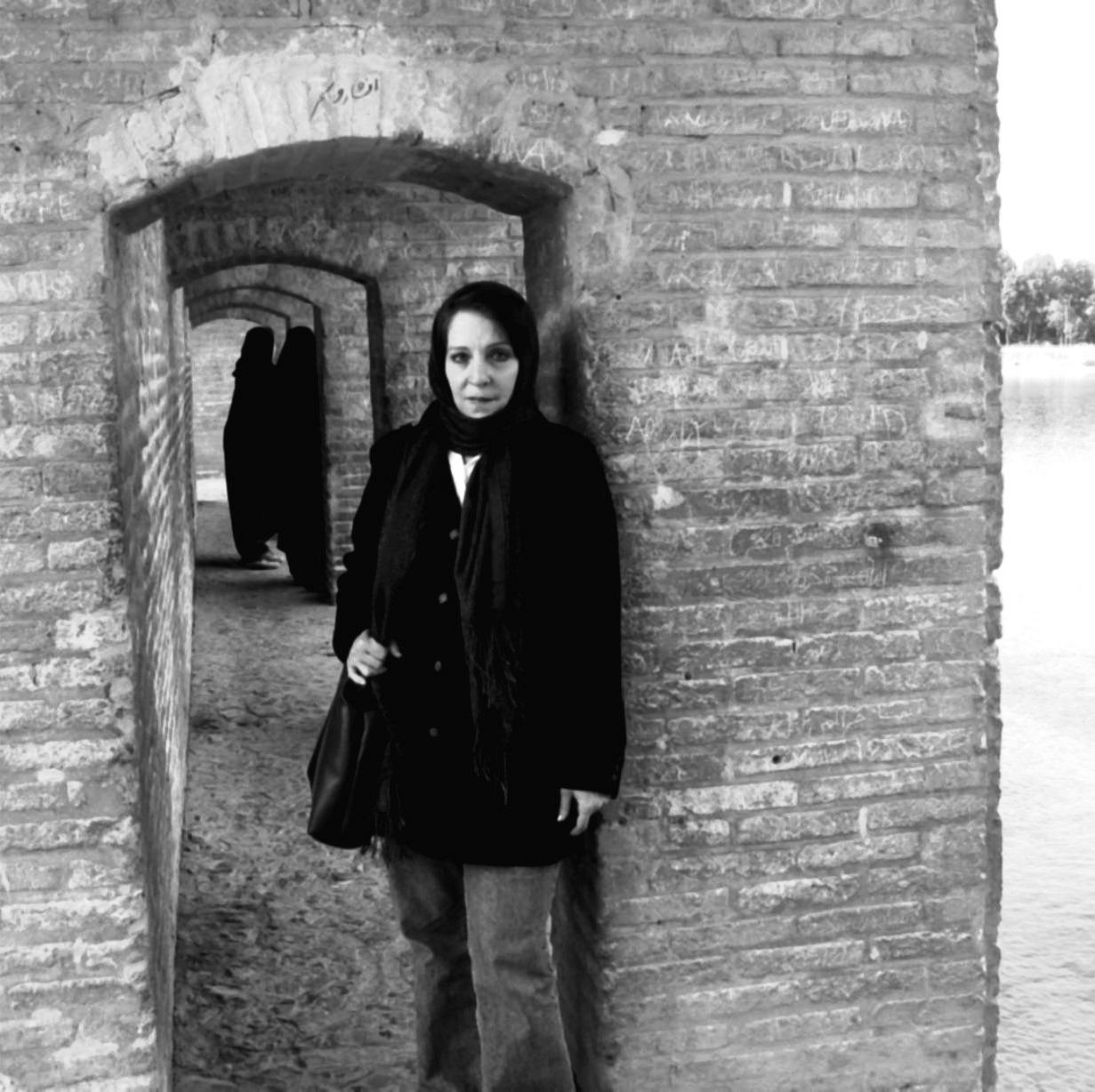

Dressing like an Iranian woman in keeping with local customs and laws

which are not supposed to be challenged is to a Caribbean woman an

exercise of modesty and self-acceptance imposed by a natural aspect

usually disguised by lipstick and eye makeup. It was hard for me to

recognize the oval of my own face when I first saw it in the mirror

fully disclosed in all its nakedness. How to give up my feminine vanity

entirely was another lesson I learned in this trip, not unlike what the

dream in Shiraz left in my mind too.

I have described that dream in writing, although it took place in

Isfahan while I was sleeping in the Malek Hotel, with its golden images

of Darius and nomadic tiles, and my confusion makes me wonder what

Cortázar’s dreams were like when he traveled to Iran and whether his

visions in Shiraz had been somehow similar to my own in this dream,

which I fail to understand but will always treasure nevertheless.

Referred to as “half of the world” because the travelers of old said

that those who arrive in this city have already seen one half of the

wonders of the world, Isfahan still surprises visitors with its magic

tricks that defy all reason and improve our bond with reality. The great

Imam Square, one of the largest in the world, mixes the lushness and

beauty of the buildings with acoustic variations, repeated sounds and

auditory dislocation. In the main entrance hall of the Ali Qapu Palace,

two persons who stand facing the wall kitty-corner twenty meters from

one another will have no trouble hearing what the other whispers. If you

shake a piece of paper lightly while standing right under the exact

center of the main dome of the Royal Mosque, a spot on the floor marked

with seven stones, you will hear the imperceptible sound echo seven

times. The way sounds are transmitted from a distance and their no less

mysterious unrestrained multiplication add to the marvels of the land

where the legend of Isfahan is set.

After the Sunday naptime dream was the turn of the optical illusion of

the oscillating minarets in the mosque where Abé Abdullah’s mortal

remains lie. Located almost in the outskirts, the small building often

attracts a sizable crowd that waits patiently to see the gravity-defying

towers: when one of them is shaken from the inside, the other starts to

move as well. From the patio we notice how the cadenced motions of a

barely visible human figure in one of the towers make both minarets

swing back and forth in unison, apparently joined in a swaying dance

that threatens to bring down the whole structure. The angle of sight

combines illusion and the magic of mirages to throws us back into a

dimension of Iranian sensibility and culture that verges on the

miraculous.

After the surreal sighting of the moving minarets came the magnificent

bridges over the Zayandeh Rud, Isfahan’s main river, which turns the

areas along its shores into a haven of peace and communion with nature.

We went first to the Sio Seh –Bridge of the Thirty-Three Arches, built

in 1602 under Shah Abbas I. A quick glance at the structure suffices to

notice once again how the close and open spaces are used, with stone

walls hiding the river away from sight except through arches that

outline the landscape. Only through the small openings leading to the

outside walkways can visitors gain access to the large stream, its real

size belied by the modesty and smallness of the approach road. Thus two

different worlds marry with each other in a dialectics that plays with

dimensions, spatial opposites and environmental traits: the bridge

proper, which you cross without seeing the landscape, and the narrow

side hallways to where the thirty-three arches giving onto the river

ultimately lead. It’s the same conception applied to the narrow,

simple-looking doors that suddenly open onto the vast spaces, as if you

have to put up with walkways so narrow as to give the impression that

they’re closing up on themselves before you’re entitled to even enjoy

the immensity of the open spaces to their fullest extent.

Several times along the way Maryam and I were slowly covering we

stumbled upon a boy who was singing down there by the banks, under the

arches, his back to the passersby. He seemed to be keeping in step with

us, as every time we thought we had left him behind he would show up

again to regale us with his wail-like, broken voice. An amazing act of

faith, his vehement dedication to the rite in the hope of seeing his

wishes fulfilled based on a yearning willingness that relied on

excessive expectations. Legend and tradition have it that a melody sung

under the arch of a bridge should alter the course of destiny and

mediate in the Gods’ decisions. The boy’s faltering voice also reminded

us of Hadeyeh’s “Faryaad” that we had heard days before in our tour

around Alborz, the mountain range north of Tehran.

The Zayandeh Rud is a quiet, shallow river. After a long walk we sat

down to wait for the lights of the Pol-e Khaju Bridge, the only ones

still off. That’s when the miracle of light and conversation occurred:

at twilight, a frog swam straight to where we were and stopped there,

staring at us. I don’t know what she was seeing, but she remained there,

impassive and impervious to the flash of my camera.

There come the worrying questions again: why did that sacred river

creature, linked to fertility and rebirth, pick the exact spot on the

long shore where we were talking about Lezama and Cortazar? Maryam came

up then with Cortázar’s notion of the shapes, and all of a sudden an

invisible drawing was configures that came all the way from Shiraz to

these Persian bridges made for walkers, such as the Pont des Arts,

crossed exclusively by pedestrians like Oliveira or the Magician. So

much for delirious dreaming, because right there and then a party of

colors broke out in the dawn’s magic brightness when the Pol-e Khaju

started to light up with Persian calm and gentleness. At first it was a

faint yellow-and-orange light not unlike that of the bonfires lit by the

warriors that roamed the valleys; then it grew, as if the troops were

multiplying, and on and on until the whole span of the bridge came to

life and began to throw reflections onto the river, while other lamps

gradually came on in a cadence that gloated over its own slowness.

The dream in Isfahan was becoming endless as it settled in the magical

feelings that reality conveyed to the magnetized city, as if echoing

seven times in a row. We felt the same light sleepiness we had

experienced with the water pipe we smoked, sprawled over cushions and

carpets, in a valley of the Alborz. It was as if I had never really

woken up and was passing instead through the region where fantasy meets

reality.

I have fond memories of my short-lived taste of the Persian culture, an

experience equally branded by the poetry of Hafiz and Omar Kayam which I

can’t but relate to the teachings and lessons that my dream in Isfahan

brought to my life.

Isfahan -Tehran- Havana, 2008

Revista Revolución y Cultura

Revista Revolución y Cultura

No. 6 septiembre-octubre 2008

Un sueño en Ispahán

Margarita Mateo

Más que un sueño, fue la entrada en una dimensión donde los objetos

hablaban un lenguaje comprensible a los hombres. Las palabras se hacían

visibles como formas definidas que proyectaban su propia sombra mientras

yo hablaba sobre el mito y la literatura latinoamericana y caribeña

en la Universidad de Teherán. El primer vocablo que se corporizó fue

una pluma de quetzal que saltó de un verso azteca y comenzó a flotar

sobre el público del anfiteatro. Luego fueron las cerbatanas de los

gemelos mayas, el cantarillo de la princesa quechua, el dios de las

semillas de sor Juana, palabras que, transmutadas en imágenes,

desparecían en el aire luego de levitar fugazmente.

Terminada la conferencia fue el encuentro con mis maestras, vivas y

muertas. Graziella, que conversaba en idioma ajeno, y Ofelia, sobre una

cama con la cabeza envuelta en un velo. Junto a ella, la anciana persa

de mirada penetrante que también me ofrecía una enseñanza. Es un

espíritu, pensé, y no debo mantener tanto rato su mirada. Aparté la

vista de inmediato y cerré los ojos. Cuando los volví a abrir, y me iban

a entregar aquellos manuscritos que no pude llegar a sostener en mis

manos, desperté. Que ese sueño haya tenido lugar en Isfahán, la mitad del

mundo, joya del antiguo Oriente, me parece revelador. De qué, no lo sé.

Pero he aprendido que tratar de descifrar algunas señales que nos oponen

resistencia puede ser el inicio del camino hacia la locura, así que no

trato de entender. Sé que hay algo, pero lo dejo ir: hands off.

Isfahán es un oasis en medio del desierto. Luego de atravesar kilómetros

y kilómetros de montañas de roca junto a una planicie árida, desolada,

sin apenas señales de vida, aparece la ciudad llena de energía y

trasiego humanos, con sus avenidas de compactas arboledas, sus calles

con nombres de poetas y sus fuentes de aguas cristalinas: puro

despliegue de humedad que desafía la aridez del desierto y la resequedad

del clima imponiendo el verde sobre el ocre de las montañas.

El palacio de Chehel Sotum o de las cuarenta columnas es considerado uno

de los más delicados ejemplos de arquitectura persa. En su majestuoso

pórtico, que aún conserva los espejos y metales brillantes de la media

cúpula de entrada al interior del recinto, eran recibidos los

embajadores extranjeros. El efecto es deslumbrante, de un brillo casi

enceguecedor. Las columnas, sin embargo, perdido su recubrimiento, se

hallan en la pura madera que antes vistió aquellos esplendores. Sostén

de la enorme estructura en cuyo centro, bajo techo, hay una fuente con

leones en las cuatro esquinas, parecen perderse en su propia altura.

La expresión en la faz de los animales de piedra es casi implorante: los

ojos almendrados, caídos en los bordes externos, las fauces abiertas en

una especie de mueca que más que rugido desafiante es un eterno bostezo

desde la intemporalidad de la piedra. El visitante no puede menos que

reparar en ese gesto detenido que lo incita a acariciar sus cabezas, a

palmear sus hocicos quejumbrosos, a sentir compasión por la fijeza de su

desamparo. Recuerdo ahora un poema persa de Hamid Mosaddegh que leí

anoche en el hotel: “León de piedra, perplejo en el polvo, tu

dignidad ahora está olvidada”.

Si se observan detenidamente las columnas se advierte que no son

cuarenta. Solo hay veinte. Las otras también existen, pero reflejadas en

el agua de las fuentes. El nombre del palacio, sin embargo, no establece

ninguna distinción entre las sólidas, pétreo apoyo del pórtico, y las

que son solo reflejo sobre el agua, pura ilusión de la mirada, temblor

espejeante. Esas columnas, ahora de madera desnuda, estuvieron

recubiertas como la semicúpula interior, de puro centelleo. En sus días

de gloria, fueron reflejo sobre reflejo, juego de espejos duplicando

luces y resplandores hasta el infinito. El nombre del palacio da una

idea de la visión persa del mundo, de su propensión a la fantasía, a la

entrada en mundos irreales, a mirar hacia otras dimensiones,

refinamiento de la sensibilidad que se hace evidente en las costumbres

de su pueblo.

Para llegar a Isfahán recorrimos un largo camino que comenzó por Quom,

la ciudad religiosa donde los mullahs realizan altos estudios y

se consagran a sus rituales durante años, para salir luego con sus

turbantes, de colores distintos según la dignidad alcanzada. Luego fue

Kashan, con sus leyendas negras y sus arañas venenosas. Y para confirmar

el halo oscuro que cubre a la ciudad, el primer lugar que visitamos fue

el Jardín de Fin, donde un sha asesinó a su primer ministro, querido y

admirado por el pueblo. En los intrincados laberintos del baño donde se

cometió el crimen, los techos bajos, los pasillos estrechos, las

torceduras de los pasadizos, los recovecos oscuros, parecen guardar la

memoria de aquella tragedia protagonizada por el rey asesino, que dejó

como un temblor, nefasto e imperecedero, en el ambiente.

En Kashan, con un calor sofocante y un sol agresivo que irritaba los

ojos y empañaba la mirada, entré en la casa de Ameriha, donde

pude sentir el cambio de temperatura del calor abrasador a la frescura

inmediata del interior. El cuerpo, doblegado bajo el velo y el manto,

resignado al azote de la canícula, es el primero en advertir el

contraste. La sensación física es muy intensa. Agradeces las celosías,

los laberintos, la oscuridad, todo lo que te mantiene alejada de ese

duro y agresivo mundo exterior. Las antiguas habitantes de la casa, que

podían despojarse del chador al penetrar el recinto, sentirían la

diferencia de temperatura con mucha más fuerza.

Para un cuerpo como el mío, habituado al ardor del trópico, donde el

calor se combate con desnudez y abanicos, con movimientos –quitar,

abrir, batir, cambiar de lugar–, el fogaje persa y la actitud

frente a él resulta una experiencia completamente nueva. El abanico, con

su batir más o menos desenfrenado, es también señal de desesperación,

combate exasperado contra el clima, muestra de inconformidad. En Irán

esos gestos son superfluos. No puedes quitarte el velo, el aire fresco

tiene el acceso prohibido. La lucha es sorda, silenciosa, invisible,

librada bajo el manto. Los gestos, que pudieran ser señal de la rebeldía

del cuerpo ante el ambiente sofocante y opresivo, habrían sido también

una falta de delicadeza con mis anfitriones. Pero además, no hubieran

resuelto nada. Ellas asumen esa lucha de manera callada, con un orgullo

y una dignidad que van más allá de la pura resignación.

En esas circunstancias el sistema de ventilación de la vivienda, los

sombreados pasillos por donde circula la brisa que los altos minaretes

atrapan para refrescarse sobre el agua del estanque, son un

descubrimiento asombroso. Luego el aire entrará de modo imperceptible en

los aposentos a través de los agujeros disimulados tras los ornamentos

de las paredes. La sensación de alivio, de ambiente placentero que sentí

cuando Mohammed me condujo a la base de la torre por donde entraba el

aire fresco en la casa de Ameriha, se reprodujo en la mansión de los

Buyerdí y en el Baño del Sultán.

Vestir como una iraní, según lo establecido, no intentando desafiar las

leyes o la costumbre, es, para una mujer caribeña, un ejercicio de

modestia y aceptación de sí misma en un estado natural generalmente

opacado por el brillo y los tonos del maquillaje. Cuando solo queda al

descubierto el óvalo facial en su plena desnudez, es difícil reconocer

la imagen propia frente al espejo. El abandono de toda vanidad fue

también una de las enseñanzas de este viaje, algo que de algún modo

también estuvo presente en el sueño de Shiraz.

El sueño de Shiraz he escrito, pero mi sueño tuvo lugar en Isfahán, en

la habitación del hotel Malek, con sus doradas imágenes de Darío y sus

azulejos nómadas, y esta confusión me hace pensar en cómo habrán sido

los sueños de Cortázar durante su viaje a Irán, si acaso sus visiones en

Shiraz no habrán sido, de algún modo, este sueño en Isfahán que no

comprendo pero que conservo como un tesoro.

Conocida como “la mitad del mundo” porque, según los antiguos viajeros,

quien llega hasta allí ya ha conocido la mitad de las maravillas que

existen sobre la tierra, Isfahán sigue sorprendiendo con sus artes de

prestidigitación que confunden los sentidos y enriquecen la relación con

la realidad. En la gran Plaza del Imán, una de las mayores del mundo, a

la exuberancia y belleza de las construcciones se añaden los juegos

acústicos, las reiteraciones de sonidos, la dislocación auditiva. En el

recibidor principal del Palacio de Alí Qapu, dos personas situadas en

esquinas diferentes, separadas a veinte metros de distancia, podrán

escuchar con nitidez los susurros que emitan de cara hacia la pared.

Bajo el centro de la cúpula mayor de la Mezquita Real, marcado en el

piso con siete piedras, si se agita levemente un papel, el eco repetirá

siete veces el sonido tembloroso de la hoja. La transmisión misteriosa

de las palabras a través de la distancia, la multiplicación desenfrenada

del sonido original son parte de las maravillas de la tierra a la que se

refiere la leyenda de Isfahán.

De aquel sueño durante la siesta de domingo pasamos a la ilusión óptica

de los minaretes oscilantes en la mezquita donde se encuentra la tumba

de Abé Abdullah. Casi en las afueras de la ciudad, la pequeña

edificación convoca un nutrido público que espera pacientemente el

momento en que se producirá el milagro de las torres que desafían las

leyes de gravedad cuando el movimiento de una de ellas, al ser sacudida

desde su interior, contagie a su semejante. Desde el patio puede

observarse cómo, al vaivén de la figura humana –apenas visible en una de

las torres–, los alminares comienzan a oscilar y la edificación parece

incorporarse a una danza cimbreante que amenaza con echar abajo toda la

estructura. El juego de perspectivas, la ilusión de la mirada, la magia

del espejismo remiten nuevamente a esa dimensión de la sensibilidad y la

cultura iraní que linda con lo maravilloso.

De la visión irreal de los minaretes movedizos pasamos a la

magnificencia de los puentes que atraviesan el Zayandeh Rud, el mayor

río de la ciudad, que convierte esa zona de Isfahán en un retiro de paz

y comunión con la naturaleza. Primero fue el Sio Seh o Puente de los

Treinta y Tres Arcos, construido en 1602 por el sha Abbas I. Nuevamente

se hace perceptible en la estructura del puente el juego con los

espacios abiertos y cerrados: las paredes de piedra impiden la

contemplación del río que sólo se hace visible a través de los arcos que

enmarcan el paisaje. Únicamente atravesando las pequeñas aberturas que

conducen a los pasillos exteriores puede accederse al universo

desmesurado del río, camuflado por la modestia y pequeñez de la entrada.

De este modo vuelven a conjugarse dos mundos diferentes en una

dialéctica que juega con las dimensiones, las oposiciones espaciales y

la semantización del entorno: el puente, propiamente dicho, por donde se

transita sin que el paisaje se haga visible, y los pequeños pasillos

laterales a los que conducen los treinta y tres arcos que dan hacia el

río. Es la misma concepción de las puertas estrechas, nada llamativas,

que de pronto se abren hacia los enormes espacios, como si para apreciar

la vastedad, en toda su extensión, hubiera que transitar primero por una

estrechez que parece cerrarse sobre sí misma.

Varias veces, durante el moroso deambular mío y de Maryam, tropezamos

con un muchacho que cantaba bajo los arcos, junto al agua, de espaldas a

los transeúntes. Parecía desplazarse a nuestro ritmo, pues aparecía una

y otra vez con su voz quebrada como un lamento cuando creíamos haberlo

dejado atrás, en un puente anterior. La vehemencia con que el

improvisado cantor realizaba el rito para el cumplimiento de sus deseos

–voluntad anhelante que confiaba en la desmesura de su esperanza– era un

testimonio sorprendente de fe. Las melodías entonadas bajo el arco de

los puentes, deberían, como reza la leyenda y atestigua la tradición,

torcer el rumbo del destino y mediar en las decisiones de los dioses. El

canto del joven anhelante con su quejosa melodía convocaba igualmente la

voz de Hadeyeh cantando “Faryaad” cuando días antes recorrimos las

laderas del Alborz, la cadena montañosa que protege a Teherán por el

norte.

La orilla del Zayandeh Rud es muy tranquila, de aguas poco profundas.

Luego de una larga caminata nos sentamos a esperar por las luces del Pol-e

Khaju que aún permanecía apagado mientras los otros puentes ya mostraban

sus esplendores iluminados. Se produjo entonces, a la tenue luz del

crepúsculo, el milagro de las luces y el milagro de la conversación. Una

rana, navegando la extensión del río, vino a situarse frente a nosotras

y a mirarnos fijamente. No sé lo que verían sus ojos, pero allí estaba

inalterable, con esa mirada detenida, inmutable ante nuestros

movimientos, impasible ante el flash de la cámara.

Vuelven entonces las preguntas inquietantes ¿por qué, de aquella

extensísima orilla, ese animal sagrado del río, asociado con la

fertilidad y el renacimiento, escogió el sitio donde hablábamos de

Lezama y de Cortázar? Maryam mencionó entonces la noción de las figuras

cortazariana, y de pronto se configuró un dibujo invisible que venía

desde Shiraz hacia los puentes persas, hechos a la medida de los

caminantes como el Pont des Arts, por donde sólo transitan los peatones

como Oliveira o la Maga; y hasta aquí el pensamiento delirante, porque

entonces comenzó la fiesta de colores en la ya mágica luminosidad del

crepúsculo, y el Pol-e Khaju comenzó a encenderse con parsimonia y

delicadezas persas. Primero fue una luz tenue, amarilla, naranja, como

una fogata encendida por los guerreros en un valle, y luego otra, como

si las tropas se multiplicaran, y otra y otra, hasta que toda la línea

horizontal de la parte alta del puente comenzó a cobrar vida, a lanzar

reflejos sobre la superficie de las aguas mientras otras luminarias iban

apareciendo poco a poco, en una cadencia que se regodeaba en su propia

morosidad.

El sueño en Isfahán se volvía interminable al prolongarse en las

sensaciones mágicas que deparaba lo real en el espacio imantado de la

ciudad, como si el eco lo estuviese repitiendo siete veces. Un estado de

duermevela, similar al provocado por la pipa de agua que fumamos sobre

cojines y alfombras en un valle del Alborz, se adueñaba de mi mirada

hacia el entorno, como si en verdad nunca hubiese despertado, como si me

moviera aún por esa región donde la fantasía se confunde con la

realidad. Ese breve acercamiento a la cultura persa, marcado también por

la poesía de Hafiz y Omar Kayam, es parte entrañable de una experiencia

que no puedo dejar de asociar con las enseñanzas y el saber que auguraba

mi sueño de Isfahán.

Isfahán-Teherán-La Habana, 2008.