El Pais

INTERVIEW: LEONARDO PADURA | CUBAN WRITER

"Cuba is racing against the clock"

Cuban writer Leonardo Padura reflects on the

"perversion" of socialism in his latest

novel "El hombre que amaba a los perros"

(The man who loved dogs).

MAURICIO VICENT

- Havana - 23/09/2009

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter

Lippmann.

We met in his house in Havana’s Mantilla

neighborhood, where Leonardo Padura has

lived since he was born 54 years ago and

written the nine novels he’s published so

far. His latest one, El hombre que amaba

a los perros (The man who loved dogs),

just released in Spain, revisits the

assassination of Leon Trotsky by

Ramón Mercader and

inquires into the perversion of socialism as

mankind’s great 20th century utopia, which

has no doubt had fallout in Cuba.

Q: How is this story topical?

A: Mercader is linked to one of the 20th

century’s most dramatic, symbolic and

revealing historic events. Moreover, his

story is relevant: a man who gave up

everything for his faith and sacrificed

himself for an ideology as strained with

scholasticism and transcendentalism as

Soviet socialism undoubtedly was; a symbol

of how fanaticism can pervert and manipulate

people. Few realities can be any more

topical.

Q: What did you find out in your

investigation that you didn’t know already?

A: For five years I consulted the most

diverse sources. What struck me most was the

huge gap in my generation’s knowledge about

the USSR’s real history and the realization

of why that country and society were doomed

to disappear: they had long been phony, sick

creatures that even committed crimes against

and betrayed their State.

Q: One of your characters says: "He felt

sorry for himself and all those who were

once cheated and manipulated into believing

in the soundness of the utopian project

presented by the late Soviet Union". Do you

share that view?

A:

Yes. Our knowledge of what happened in the

USSR was partial and selective, as we were

led to believe in something whose countless

dark features we knew nothing about. We

thought, or they tried to make us think,

that all Soviets were our brothers and

sisters, that mankind’s future belonged

entirely to socialism, and other tenets

along those lines that carried within a

whole history forged by Stalin and his

accomplices, an ideology sold to us as the

ultimate expression of humanism but actually

fed with the blood of ten to fifteen million

victims and the sweat and hopes of many

other millions of followers.

Q: The main character almost forgives

Mercader. Do you?

A: I have tried to understand him and

his reasons. I admit that at the end, almost

abandoned to his fate and aware he had been

used and deceived, he may arouse some

compassion. However, I don’t forgive him.

Even in the strictest totalitarianism

there’s always a glimmer of hope for ethics

that caters to an individual’s principles

and allows them to say no to what’s

unbefitting instead of engaging in something

as reprehensible as crime, denunciation and

treason.

Q: What was socialism’s main deception?

A:

Stalinism, no doubt. Stalin’s greatest

betrayal was the extent of the political,

economic, philosophical, ethical and even

aesthetic perversion caused by his

misappropriation of an idea and a revolution

intended to create a fully egalitarian

society that provided its members the best

possibilities for fulfillment. Stalinism was

eventually exported, becoming a legacy

which, together with other methods and

faces, thwarted the consummation of man’s

greatest utopian dream: a society of equals.

Q: What has the

Soviet socialist model bequeathed to Cuba?

A:

I

think that Cuba tried, and successfully so

to a great extent, to come up with its own

model ever since the Revolution declared its

socialist character. Only that can explain

why socialism collapsed in the Soviet Union

while Cuba kept, by itself and against the

U.S. embargo and hostility, its social and

political structures... Of course, some

important things are still in place, like a

centralized economy and the fact that most

means of production, including the land, are

in state ownership, among other issues now

under discussion and probably about to be

changed soon. Only through far-reaching

transformations of the old model can Cuba

start to think about a possible socialism, a

more egalitarian society based on an

economically feasible project.

Q: Many characters in this and other

novels you have written are disappointed and

regretful individuals, people eager to leave

the country, tired of putting their own

dreams before the collective aspiration, fed

up with the state meddling in everything...

A: Since the late 20th century the Cuban

narrative has approached what has come to be

known as the literature of disillusionment,

which reflects not only the crisis we have

lived through since then but also –and above

all else– individual weariness. A life in

exile that so many Cubans have chosen is an

expression of that disillusion, much like

the option of criticism and debate by many

of those who chose to stay in the Island.

Q: Can Cuban socialism be reinvented or

is it already exhausted?

A: I’m not a politician, so I can’t say

whether the model is exhausted. As a citizen

familiar with much of the hardship,

adversity and dogmatism we have suffered for

years, I have to acknowledge that it still

exists twenty years after the fall of the

Berlin Wall. But as a writer and man of

ideas, I think another utopia must be

recast, for Cuba as well as for the whole

world.

Q: When Raúl took office many people

hoped change was coming. It’s been almost

three years...

A: Cuba is racing against the clock,

which is ticking faster and faster. We’re

dealing with very heavy burdens that

threaten our stability and future, such as

the inefficiency of a suffocated economy

that seems unable to find the right way

toward productiveness; rampant

marginalization and corruption, especially

by and among those who have some power; an

oppressive and parasitic bureaucracy; the

pile-up of various pressing needs like

housing, food, a topsy-turvy income/expenses

ratio; lack of organization, etc. That we’re

still capable to change whatever needs to be

changed and make the structural and

conceptual changes that he mentioned –but

are yet to be defined– remains to be seen.

Q: Everything is still in the hands of

the historic figures...

A: We in Cuba have lived for almost

twenty years in the midst of our own

economic crisis. Before that we went through

the shortages and sacrifices of the 1960s

and 70s, without forgetting the quite rigid

orthodox policies we had in those years.

[Those policies] that discriminated

against religious believers and homosexuals

and condemned any dissent, to the point of

consigning to years of intellectual oblivion

anyone who would say something like what I’m

telling you now. It’s as a result of that

persistent crisis that many people leave

Cuba today or just get tired. However, I

think that it’s precisely because of having

been through so much sacrifice and necessity

that the Cubans deserve a better future and

the right to criticize. So those in

government, be they “historic” or “emerging”

figures, are duty-bound to respond to such

demands, to make the changes needed to

preserve what’s usable and find solutions to

what’s yet to be solved.

A: How did you like [Colombian rocker]

Juanes’s concert at the Revolution Square?

A: I think it was great. A concert in

Cuba without political slogans and where

peace and understanding stand as the main

message is an extraordinary and necessary

event. It sent a fresh message and was a

sharp shock to stagnation... whatever means

to an opening is important anyway.

Q: What’s the major challenge facing Cuba

today?

A: Holding on to the dream of a better

society is far and away a major

responsibility toward history. Our greatest

challenge would be to maintain in practice a

project that includes all Cubans, protect

society from a catastrophic collapse, and

make sure everyone has a decent living:

Martí’s Republic, to be built “with all and

for the good of all".

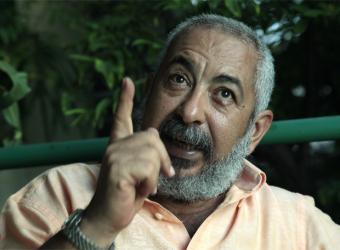

El escritor cubano

Leonardo Padura, durante la entrevista

en el patio de su casa en Mantilla, cerca de La

Habana.

- JOSE GOITIA

ENTREVISTA: LEONARDO PADURA | ESCRITOR CUBANO

"En Cuba se libra una lucha contra el tiempo"

El escritor cubano Leonardo Padura reflexiona sobre la "perversión" del socialismo en 'El hombre que amaba a los perros', su última novela

MAURICIO VICENT - La Habana - 23/09/2009

La entrevista se celebra en su casa habanera del barrio de Mantilla, donde Leonardo Padura ha vivido desde que nació, hace 54 años, y donde ha escrito las nueve novelas que ha publicado hasta ahora. La última, El hombre que amaba a los perros, recién salida en España, revive el crimen de Ramón Mercader, el asesino de León Trotsky, y reflexiona sobre la perversión del socialismo como gran utopía de la humanidad en el siglo XX. Una utopía que, desde luego, tuvo consecuencias en Cuba.

Pregunta. ¿Qué tiene de actualidad esta historia?

Respuesta. Mercader es un hombre que estuvo alrededor de uno de los acontecimientos históricos más dramáticos, simbólicos y reveladores del siglo XX. Su historia, además, es permanente: un hombre que renuncia a todo por una fe, que se inmola por una ideología cargada de escolástica y trascendentalismo, como sin duda fue el socialismo soviético. Mercader es un símbolo de cómo el fanatismo es capaz de pervertir y utilizar a los humanos, y pocas realidades pueden ser más actuales.

P.¿Qué cosas descubrió durante la investigación que no sabía?

R. Durante cinco años consulté las fuentes más diversas. En todo ese proceso lo que más me impresionó fue descubrir lo poco que sabíamos los cubanos de mi generación de lo que había sido la verdadera historia soviética y comprender por qué ese país y esa sociedad debían desaparecer: eran criaturas falsas y enfermas desde hacía muchísimo tiempo que, incluso, practicaron la traición y el crimen de Estado.

P. Uno de los protagonistas de su libro dice: "sintió pena por él mismo y por todos los que, engañados y utilizados, alguna vez creyeron en la validez de la utopía fundada en el desaparecido país de los Soviets". ¿Compartes esta reflexión?

R. Sí. Nuestro conocimiento de lo que ocurrió en la URSS fue parcial y seleccionado, se nos hizo creer en algo de lo que no conocíamos las entrañas más oscuras, que eran muchísimas. Creímos -o trataron de que creyéramos- que cada soviético era un hermano, que el futuro de la humanidad pertenecía por completo al socialismo y otras frases así. Y con aquellas frases iba toda una historia falsificada por Stalin, sus cómplices y sus seguidores, una ideología que se presentaba como la consumación del humanismo pero que en realidad arrastraba la sangre de diez, quince millones de víctimas. Y el sudor y la esperanza de otros muchísimos millones de creyentes.

P.El protagonista de la novela casi llega a perdonar a Mercader. ¿Y usted?

R.Yo he tratado de entenderlo, de buscar sus razones. No niego que su final, casi abandonado, sabiendo que había sido utilizado y engañado, llega a provocar una cierta compasión. Pero no lo perdono, eso no. Siempre queda, incluso en el totalitarismo más férreo, un resquicio ético que el individuo puede manejar desde sus propias convicciones y que te permite decir que no ante lo inadmisible y no convertirte en parte de algo reprobable, como el crimen, la delación, la traición.

P.¿Cuál fue la principal estafa del socialismo?

R. El estalinismo, sin duda;. Las proporciones de la perversión política, económica, filosófica, ética y hasta estética que implicó la apropiación por parte de Stalin de una idea y de una revolución que pretendían crear una sociedad con la mayor equidad social y con las máximas posibilidades de realización humana, fue la mayor traición. El estalinismo se exportó y se convirtió en legado y, con otros métodos y rostros, frustró la realización del gran sueño utópico de los hombres: la sociedad de los iguales.

P.¿Qué ha dejado en Cuba la copia del modelo socialista soviético?

R. Creo que Cuba, desde que se anunció el carácter socialista de la revolución, trató de crear su propio modelo. Y en buena medida lo logró: solo así se entiende que haya desaparecido el socialismo soviético y europeo y que Cuba, sola y con un embargo y la hostilidad norteamericana, haya mantenido su estructura política y social... Pero, claro, quedaron cosas importantes, como la economía centralizada, la mayoritaria propiedad estatal de los medios de producción (incluida la tierra) y otras que hoy se discuten y que, quizás, pronto sean cambiadas. En Cuba, solo con transformaciones esenciales del viejo modelo puede empezar a pensarse en un socialismo posible, en una sociedad más equitativa y que económicamente sea un proyecto viable.

P. En esta novela y en otras suyas muchos personajes son gente decepcionada y arrepentida. Gente que se quiere ir del país, que está cansada de anteponer los sueños individuales a los colectivos, harta de que el Estado se meta en todo...

R. Desde los años finales del siglo pasado en la narrativa cubana se ha trabajado lo que se ha dado en llamar la literatura del desencanto, que no es solo un reflejo de la crisis que vive el país desde entonces, sino y sobre todo, del cansancio de los individuos. El exilio al que se han ido tantos cubanos es una de las manifestaciones de ese desencanto. Pero también lo es la opción por la crítica y el debate de muchos de los que nos hemos quedado a vivir en la isla.

P.¿El socialismo cubano puede reinventarse o ya está agotado?

R.Yo no soy un político y no sé si el modelo está agotado, porque de hecho se ha sostenido veinte años después de la caída del muro de Berlín. Pero como ciudadano que he vivido muchas de las carencias, vicisitudes y dogmatismos que nos han asediado por años. Como escritor y hombre de pensamiento, creo que se necesita refundar una utopía y no solo para Cuba, sino para todo el mundo.

P.Al llegar al poder Raúl mucha gente albergó expectativas de cambio. Han pasado casi tres años...

R. En Cuba se libra una lucha contra el tiempo, y cada vez hay menos tiempo. Hay lastres muy pesados y peligrosos para la estabilidad y el futuro del país: la ineficiencia y la asfixia de una economía que no acaba de encontrar cauces productivos; el crecimiento de la marginalidad y la corrupción (y corruptos son, sobre todo, quienes tienen algún poder); el burocratismo agobiante y parasitario; la acumulación de necesidades muy diversas (vivienda, alimentación, la relación desquiciada entre salario y costo real de la vida, etc.); la desorganización... Hace falta ver si todavía hay capacidad para cambiar todo lo que debe ser cambiado, introducir esos cambios estructurales y conceptuales que se mencionan pero no se definen.

P.Todo sigue estando en manos de los históricos...

R.Los cubanos llevamos casi veinte años viviendo en medio de una crisis económica propia, y antes vivimos todas las carencias y sacrificios de los años sesenta y setenta -incluida en ese tiempo la más férrea ortodoxia política que marginaba a religiosos, homosexuales, y condenaba cualquier desacuerdo y que, por respuestas como las que le doy ahora, me hubieran caído encima años de marginación intelectual-. Por esa persistencia de las crisis hay tantos que emigran o se agotan: pero precisamente por haber soportado tantos sacrificios y necesidades, creo que la gente en Cuba se merece un futuro mejor y el derecho a la crítica. Entonces, ya sean los 'históricos' o los emergentes, el deber de los que gobiernan es responder a esa necesidad e introducir los cambios que preserven lo aprovechable y que procuren soluciones a lo no resuelto.

P.¿Qué le pareció el concierto de Juanes en la Plaza de la Revolución?

R.Me pareció muy bien. Un concierto sin consignas políticas, en el que el mensaje principal es la paz y la comprensión, eso en Cuba me parece una cosa extraordinaria y necesaria. El concierto tuvo un mensaje renovador, fue un revulsivo de cosas que están anquilosadas... Todo lo que sea apertura, en cualquier sentido, es importante.

P.¿Cuál es el mayor reto de Cuba hoy día?

R.Preservar el sueño de una sociedad mejor es, sin duda, una de las responsabilidades históricas. El mayor desafío sería sostener en la realidad un proyecto que incluya a todos los cubanos, que evite un desplome social catastrófico y que garantice una vida digna a todos: la República Martiana que se construiría "con todos y para el bien de todos".

© EDICIONES EL PAÍS S.L. - Miguel Yuste 40 - 28037 Madrid [España] - Tel. 91 337 8200