In early July, Rolando Sarabia, 23, one of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba's

leading dancers, sneaked across the border into the United States in the

way, he said, that so many Cubans do: "Walking, walking, walking." His is

the latest in a wave of defections that have hit the brilliant but

beleaguered Cuban national ballet company since 2002.

His departure, which was first reported by the Spanish newspaper El País, will be keenly felt in Cuba. Critics have called him the "Cuban Nijinsky" and compared him to the young Mikhail Baryshnikov. A company dancer since 1999, he has won ballet competitions in Paris; Varna, Bulgaria; and Jackson, Miss. Christened Sarabita by his many fans, Mr. Sarabia is the love object of at least half the adolescent balletomanes in Cuba, of which there are many.

Mr. Sarabia said his decision to leave Cuba was purely artistic, spurred, he added, by the refusal of Alicia Alonso, the general director of the Ballet Nacional, to allow him to accept a principal dancer contract with the Boston Ballet in 2003. "Artistically, they shut the door on me," he said yesterday by telephone from Miami. "I am now making a new life." He and another principal dancer with the Ballet Nacional, Alihaydée Carreño, who left Cuba to dance in the Dominican Republic this July, are both scheduled to perform in the International Ballet Festival of Miami in September, according to Pedro Pablo Peña, the director of the festival.

Officials at the Ballet Nacional de Cuba could not be reached for comment.

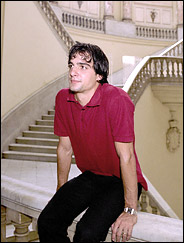

Rolando Sarabia, a former dancer with the

Ballet Nacional de Cuba, at a ballet studio in Texas.

Rolando Sarabia, a former dancer with the

Ballet Nacional de Cuba, at a ballet studio in Texas.

Don McClain

Like other leading dancers in the Cuban ballet, Mr. Sarabia has been longing to establish himself as an international star. "Where did Alicia Alonso become famous?" Mr. Sarabia said in an interview in Havana last November. "In New York. Where has she always been? Abroad." He said he wanted the same thing. "All the sacrifices I've made for my career, God should give me the opportunity," he said. "The time is now."

But God and opportunity are tricky forces, and Mr. Sarabia had to wait eight months for his moment to come. This summer, he obtained permission from the Cuban government to travel to Mexico to teach ballet in Querétaro. In early July, he said he crossed the border to the United States illegally, and after spending a week in Texas with friends, went to Miami to stay with relatives and apply for political asylum. Mr. Sarabia's younger brother, Daniel, 20, defected last year, and in June, won a silver medal at the New York International Ballet Competition. Daniel will have his debut with the Boston Ballet as a corps de ballet member in its 2005-6 season.

Officials at the Boston Ballet said they still hoped to hire Rolando Sarabia as a principal dancer. "He still has some working documents to sort out before we can offer him a contract, but we certainly would expect to," said Valerie Wilder, the company's executive director. "I'm glad he's here now and we can look forward to having him here on the stage in Boston."

There are many ways for a performer to leave Cuba. Last November, 43 members of the "Havana Night Club" revue in Las Vegas applied for political asylum after they entered the United States.

The dancer Rolando Sarabia in the Gran Teatro

de La Habana in May.

The dancer Rolando Sarabia in the Gran Teatro

de La Habana in May.

David Garten

Some dancers - like Carlos Acosta and Jose Manuel Carreño - manage to win the blessing of Ms. Alonso to bring Cuban dance to the world stage. They maintain their ties with Cuba and travel back and forth freely. Mr. Acosta, who now is a principal guest artist with the Royal Ballet, regularly performs with the Ballet Nacional de Cuba, gives the company part of his earnings and sends videotapes of his performances back to Cuba, where they are broadcast on state television, he said.

Mr. Acosta is much envied by Cuban dancers, including Mr. Sarabia. "Jose Manuel Carreño and Carlos Acosta were authorized to leave by the country and by Alicia Alonso," Mr. Sarabia said yesterday. "I think I have the right, like they do, to enter and leave my country, but in this moment, it's not so. It's very sad."

Such harsh realities seem to make Mr. Acosta feel genuinely sad. "I understand the envy, but what can I say to them?" he said in a phone interview from London earlier this year. "Talent is not enough sometimes. I have every reason to believe in fate. This is my destiny. Maybe it's not theirs."

Defection is a prickly subject in Cuba. There is no word in Cuban Spanish for "defect." Most people elide the issue by simply saying someone stayed ("quedarse") abroad. Those who are less friendly use the pejorative "desertar," which bears a heavy political load. Even frustrated dancers are loath to cut ties with their homeland. "This is my company," Joel Carreño, a principal dancer with the Ballet Nacional, said last year. "It is what has taught me everything. It is the company that has made me what I am."

In 2002-3, some 15 Ballet Nacional dancers, mostly from the corps de ballet, defected. In the summer of 2003, before the company embarked on a United States tour, Ms. Alonso and Abel Prieto, the minister of culture, forced all the dancers to sign an amendment to their contract, which stipulated that if they left the company they would not be able to return to Cuba for five years, and their families would not be able to leave for five years. This law has long been on the books, but it has been unevenly enforced, according to Ismael Albelo, a dance specialist at the Cuban Ministry of Culture. Dancers saw the move as a scare tactic; the company saw it as a one-time emergency measure to stem the flood of dancers out of the company.

Five more defected during the tour anyway.

Dancers have always left the Ballet Nacional, and at times the diaspora has been acute, but the company, fueled and refueled by the talent pouring out of Cuban dance academies, is still going strong. And though there are rising stars in the company, the recent losses of Mr. Sarabia and Ms. Carreño mean that the company is down to just two established stars: Joel Carreño and Viengsay Valdéz, both of whom have expressed interest in building their international careers.

Whether and how that might be possible remains unclear. Asked in November whether it is possible for dancers in her current company to do what Jose Manuel Carreño and Carlos Acosta did - namely to dance most of the year abroad but maintain their Cuban ties - Ms. Alonso abruptly ended the interview. "You are talking about two great stars we have given to the world," she said. "O.K. Thank you. I think I have a phone call, and I have to attend to other things. Thank you."