| |

|

June 22, 2009.

A

‘botellón’ in Havana

On

weekends, like in any other country, young people gather by the hundreds

somewhere in Havana – Starting at 9:00 p.m. and until the early hours of

the morning, G Street comes to life amidst a strict division by age and

trend – While seeing to it that these boys and girls refrain from taking

more alcohol or pills than they should, the police impose fines on those

of them who step on the grass! On

weekends, like in any other country, young people gather by the hundreds

somewhere in Havana – Starting at 9:00 p.m. and until the early hours of

the morning, G Street comes to life amidst a strict division by age and

trend – While seeing to it that these boys and girls refrain from taking

more alcohol or pills than they should, the police impose fines on those

of them who step on the grass!

By Fernando Garcia, Havana correspondent –

22/06/2009

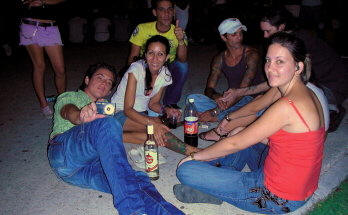

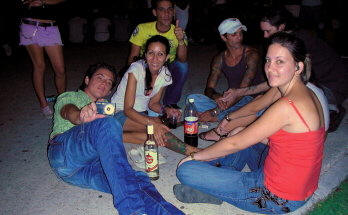

Rather

than a liter bottles, what these youths in Havana drink is rum and

Tukola, Cuba’s version of Coca-Cola Rather

than a liter bottles, what these youths in Havana drink is rum and

Tukola, Cuba’s version of Coca-Cola

Rockers, gothics,

emos, regaetton fans... Some call themselves

freakies

–even if they’re nothing but rock

music lovers– and others punkies, albeit they’re

more on the well-behaved side. Still others dress like ‘vampires’

but soon prove to be just on the pickup. A few of them admit to being

mickies, a term equivalent to ‘pijo’ –a posh kid who speaks and

dresses in an affected way– that seems to come from Mickey Mouse, “that

stupid cartoon”, as the anti-mickies say. A small number of them,

regardless of what tribe they belong to, are troublemakers, although

it’s the repas (from reparto, the word for a given area or

neighborhood) who take the cake for that. At any rate, most seem to be

absent-minded, much like teenagers most everywhere else, only more

naïve-looking.

They’re the youths of G Street, the area in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood

where they hang out together every weekend: it’s the nearest thing to a

botellón à la Cuba, a singular island increasingly less isolated

and more resistant to the fashion invasion. From Friday to Sunday the

Cuban botellón begins at around

9:00 p.m. and stretches over till dawn. It’s not really a botellón

proper, as they drink beer from cans or small flasks instead of liter

bottles, and rum and the local coke Tukola are the in thing, sometimes

in an explosive combination with pills or carefully selected medicines,

since in Cuba everyone seems to carry a doctor inside.

These youngsters wander around the boulevard; sit on benches or the

floor; chat and listen to music, be it their own or the tunes coming

from either a nearby car or the mp3 owned by a privileged member of the

gang. They come to G Street for lack of a better place, as there are

very few bars and discos in Havana. For one reason or another, many were

closed down by the Revolution, and most of those still open are

prohibitively expensive: half your salary goes on the ticket and a

couple of beers alone. What they do resembles the Spanish botellón,

only in more difficult conditions.

“The streets are free”,

Jennifer Hernández points out. She’s the keyboard player for the rock

band Escape, and came this evening with the group’s sound

technician and producer, plus two of her friends, a doctor and a

biologist. At 25 or 26, they’re the oldest ones around, and as such

settle on the upper side of this sloping avenue perfectly arranged by

ages and trends: way up there are the vets, many of them

musicians, who ‘founded’ this zone about ten years ago, while as you go

down the street, right after the corner of 23rd, you find “all the

others, who started to come in higher numbers when they realized it was

not a very bad idea after all”, she says proudly.

Both of our fascinating evening forays into G Street were utterly

peaceful. You can hear the low murmur of people speaking at a bearable

level, interrupted now and then by the occasional serenade of inconstant

quality. Small groups of uniformed cops are checking IDs, and sometimes

fine a kid who walks on the grass! “That’s because the flowers here are

so beautiful!,” a girl says ironically, pointing at a dull hedge with

her chin as she taps her temple with her forefinger.

Also doing their round are some plain-clothes policemen, another girl

whispers. Together with one or two Baptist pastors or evangelists who

drop by to try and make the lost sheep return to the fold, they’re the

real G Street freakies, the only ones yet to join a community of

usually peaceful, if at times rowdy, tribes, mainly after one drink or

pill too many.

Typically callow, clad in tight-fitting outfits and Converse sneakers,

and wearing flattened hairdos, the emos are a favorite target for

criticism, insults and, every once in a while, a slap from the

competition. Their deliberate trend towards having the blues and

injuring themselves –they’re into cutting their arms– has earned them

little affection. “We shun them because they have no sense of

responsibility; they don’t know where they come from or where they’re

going to”, rock singer Jorge Alvarez explains boldly and with a touch of

scorn. His pal Dionisio goes even further: “I would kick their ass.

They’re so shallow and without jany judgment”.

Nevertheless, the quarrels in G Street seldom go beyond that, and –they

say– are less frequent, thanks on one hand to public pressure, namely

letters that area residents have sent to the Granma daily, and

on the other to the recent, strategic decision to jam-pack the street

with lamp posts. However, the new direction (a revolutionary euphemism

for command or resolution) is at odds with the country’s energy-saving

measures, so the authorities are busy trying to put G Street in the

happy medium between complicit darkness and revealing brightness.

None of the drink stands along the promenade is allowed to sell alcohol

after 8:00 p.m., a decision as useless as it is absurd, since they can

get booze without a hitch in any neighboring side street, not to mention

that many of these kids bring bottles they bought in shops elsewhere.

Moreover, you can get anything from any of the illegal vendors who walk

up and down the street selling stuff they carry in their backpacks. The

police know that and they persecute them, but their main goal is to keep

the boys and girls in line and prevent syringes from making a comeback

after the scandal that set off the alarms not long ago.

Doesn’t all this ring any bells? Cuba is also G Street, the

Cuba that’s gradually changing and becomes less and less

different every day.

---ooOoo---

Vindicating themselves

What matters

about G Street is that it exists and survives, a Cuban sociologist well

versed in this topic remarks. Under a watchful eye, true, but there they

are, the tribes of Havana’s youth: every inch an island within a system

that made sure no public space was institutionally unoccupied. Other

spots like the areas around the Capri Hotel, the ice-cream parlor

Coppelia or the seawall avenue right off 23rd Street –now taken by the

gays– were once the target of regular oustings, and even G Street

witnessed similar cleansings. Today, however, “there are signs of a

change of strategy”, we’re told. After all, the G Street kids don’t look

particularly vindictive, nor do they seem to question the existing

status quo. They’re rather demanding their right to be and remain here

together, listening to music and having a few drinks. Do they talk about

social problems? Sure, but “not much”, say Jennifer Hernández and her

buddies. “Here we forget about everything. We don’t get mad. We already

have a lot to lose sleep over as it is: food, transportation, money… our

life. We come here to have fun, so there’s no point worrying about

revolts. Besides, no one is completely happy with their country,

right?”, they wonder. The short answer goes without saying. The long one

wouldn’t fit in here.

http://www.lavanguardia.es/internacional/noticias/20090622/53729261288/botellon-en-la-habana.html

|

|

|

| |

|

Cientos de jóvenes se reúnen el

fin de semana en una calle de la capital cubana, casi como en cualquier

país | La calle G se anima a partir de las nueve y hasta altas horas,

en rigurosa división por edades y tendencias | La policía multa a los

chicos ¡por pisar el césped! y vigila que el alcohol y las pastillas no

hagan estragos

Rockeros, góticos, emos,

reguetoneros... Unos se dicen freakies sin pasar de

adeptos al rock. Otros se tienen por punkies, aunque su talante es

modosito. Algunos van de “vampiros”, pero pronto se

delatan como ligones. Los menos se confiesan mickies, término

equivalente a pijo y al parecer derivado de Micky Mouse, (“ese

muñequito estúpido”, según los anti-mickies). Unos pocos buscan

jaleo, no importa de qué tribu sean aunque la fama en eso la llevan

los repas (reparteros, de reparto o barrio). Y la

mayoría parecen muy despistados: como los adolescentes de cualquier

otro país, sólo que con un plus de candidez.

Reivindicarse a sí mismos

Lo importante de la

calle G es que existe y sobrevive, nos dice

un sociólogo cubano que ha estudiado el tema.

Bajo estrecha vigilancia, sí, pero ahí están

las tribus de La Habana joven: toda una isla

en un sistema que siempre ocupó

institucionalmente los espacios públicos.

Otras zonas de La Habana como la del hotel

Capri, la heladería Coppelia o Malecón a la

altura de 23 –ésta última ahora tomada por

los gays- fueron en su día objeto de

desalojos periódicos; incluso en G hubo

tentativas de limpieza. Pero hoy “se

vislumbra un cambio de estrategia”, nos

explican. Al fin y al cabo, los chicos de G

no se muestran especialmente reivindicativos

ni parece que vayan a cuestionar estructura

alguna. Más bien se reivindican a si mismos;

el derecho de ser y de estar aquí juntos,

escuchando música y tomándose algo. ¿Hablan

de problemas sociales? Seguro, pero “no

mucho”, dicen Jennifer Hernández y sus

colegas. “Aquí nos olvidamos de todo. No nos

ponemos bravos. Bastante tenemos con

preocuparnos a cada rato de la comida, el

transporte, el dinero… De la vida. Aquí

tratas de divertirte. Pensar en sublevarse

no tiene sentido. Además, nadie en su país

está del todo contento, ¿no?”, preguntan. La

respuesta corta es obvia. La respuesta larga

no cabe.

Son los jóvenes de la calle

G, el punto de reunión de cada fin de semana en el habanero barrio

del Vedado: lo más parecido al botellón pero con las singularidades

de Cuba, una isla peculiar pero cada día menos aislada y resistente

al invasor de la moda. El botellón cubano dura de

viernes a domingo. La animación empieza sobre las nueve de la noche

y se estira hasta el amanecer. Botellón, lo que se dice botellón, no

es. Aquí no hay litrona de cerveza, sino lata o botellín. Y se

estila más el ron con Tukola, la cola local, a veces en explosiva

combinación con pastillas o fármacos cuidadosamente seleccionados:

en Cuba todo el mundo parece llevar un médico dentro.

Los chavales deambulan por el bulevar, se sientan en un banco o en

el suelo, charlan (mucho), cantan y escuchan música: la que hacen

ellos, la que sale de un coche o la del mp3 de un privilegiado de la

pandilla. Los jóvenes habaneros van a G porque no

tienen otro sitio donde ir. En la capital faltan bares y discotecas:

la revolución cerró la mayoría por alguna razón, y los pocos que

quedan resultan prohibitivos: con la entrada y un par cervezas se va

medio sueldo. El origen es parecido al del botellón español, pero

desde condiciones más difíciles.

“La calle es gratis”, nos resume Jennifer Hernández.

Ella es la teclista del grupo rockero Escape y en su

cuadrilla de esta noche están el técnico de sonido y el productor

del grupo, más una médico y una bióloga amigas suyas. Todos tienen

entre 25 y 26 años. Son “los viejos” del lugar, que pueblan la parte

alta de una avenida perfectamente estratificada por edades y

tendencias: arriba, los veteranos que fundaron la zona hace

unos diez años, muchos de ellos músicos; abajo, a partir del cruce

con la calle 23, “todos los demás, que fueron viviendo al ver que

nuestra idea no era tan mala”, dice Jennifer con orgullo.

En las dos noches de nuestra fascinante incursión en G, la paz es

casi absoluta. Hay un murmullo general de volumen tolerable salteado

por ocasionales serenatas de calidad variable. Grupitos de

policías uniformados piden papeles y, a veces, ponen multas

a los chicos ¡por pisar el césped! “Es que hay una flores tan lindas”,

ironiza una chica señalando un insulso seto mientras con el índice

se da golpecitos en la sien.

También rondan el paseo algunos polis de paisano, nos sopla

otra chica en bajito. Ellos y algún que otro pastor baptista o

evangelista que vienen a captar almas descarriadas son los

verdaderos freakies de G; los únicos no integrados

en una comunidad de tribus casi siempre pacíficas aunque no siempre

tolerantes entre si; sobre todo cuando el alcohol y las pastillas

hacen horas extra.

Los emos, muchos de ellos imberbes y caracterizados por su vestir

ceñido, sus zapatillas de marca Converse y por el cabello aplastado,

son el mayor blanco de críticas, insultos y algún guantazo de la

competencia. Su deliberada tendencia a la depresión y sus

prácticas autolesivas (les da por hacerse cortes en los

brazos) no les han granjeado grandes simpatías. “Marginamos a los

emos por su falta de conciencia; no saben de dónde vienen ni a dónde

van”, explica sin rubor Jorge Álvarez, cantante de rock. Otro de su

ramo, Dionicio, va más lejos: “Yo les atacaría. Son gente

superplástica y sin criterio”.

Pero las disputas en G no suelen llegar a mayores y –según nos

aseguran– se han reducido: en parte por la presión de los vecinos y

de sus cartas en Granma, y en parte por la reciente y

estratégica decisión de iluminar a tope la calle. Ahora, esta

orientación (eufemismo revolucionario de orden o

resolución) choca con las medidas de ahorro en el país, y la

autoridad busca para G un término medio entre la oscuridad cómplice

y la claridad delatora.

La venta de alcohol está prohibida en los garitos

del paseo a partir de las ocho: una medida entre inútil y absurda

cuando en algunas cercanas bocacalles se compra bebida sin problema.

Además, muchos chavales se traen las botellas de la tienda. Y no

faltan vendedores clandestinos de casi todo, incluso de vino que

transportan en mochilas. La policía lo sabe y lo persigue, pero su

objetivo principal es que nadie se pase de la raya: que no se repita

el escándalo de la aparición de jeringuillas en la zona, que hace

algún tiempo disparó las alarmas.

¿A quién no le suena todo esto? Cuba también es la calle G.

La Cuba que va cambiando. La que cada vez es menos

diferente.

|

|

|