Mysteries and illuminations of Chavarría’s Edgar Prize

http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2002/05/07/cultura/articulo02.html

An exceptional moment for

Latin American detective stories in the United States

By: Pedro de la Hoz

A CubaNews translation by Ana Portela.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

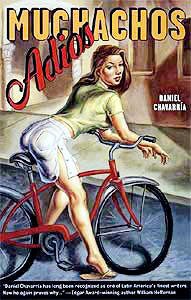

[Cover of English edition.]

Some may have been surprised, others not. That a book by Daniel Chavarría,

Adiós muchachos, has been proclaimed winner of the 2002 Edgar Prize

as the best original novel in popular format (best original paperback) may be

surprising in the English speaking literary world because, never before, had a

Latin American been able to break into a spot reserved for those who speak the

language of Poe. But for those who have followed this Uruguayan writer, living

in Cuba for three decades, and who has become so at home that his writing is

considered ours, there isn’t the slightest doubt about his narrative as the most

unique and singular detective or criminal novel literature. The Edgar Allen Poe

is an old important prize sponsored by the North American Associations of

Mystery writers (headquartered in New York) that began granting these awards

half a century ago to literary works, both fiction and testimonials, to

critical-biographical studies and today includes television and film

productions. To get an Edgar is like conquering the route for other U.S. prizes

such as the Oscar (for films), the Grammy (for music) and the Tony (for

theater). Writers, critics and journalists vote to nominate five works in each

of the twelve categories – nomination of itself is an important publicity boost

– and then meet again to vote for the prize. The board offers honorary prizes in

the fields of edition and promotion; the most important of all, the Special

Award, went this time to the filmmaker Blake Edwards, known by us for his series

of the Pink Panther.

The category for which Chavarría was nominated and later awarded is different

from the Best Novel in answer to editorial techniques: some texts are better

published in hard cover and are, therefore, more expensive and others in popular

editions or pocketbook as is Adiós muchachos by Akashic Books in

2001. The publishing house received an unprecedented success with the story of

the Cuban-Uruguayan, much reported by the critics because of his ingenuity and

humor in the description of the ups and downs of a prostitute who solicits from

her bicycle in Havana during the hard years of the special period. Chavarría’s

contenders were all heavy weights in U.S. detective literature: Hell’s Kitchen

published William Jeffries (alias of Jeffrey Deaver) whose horror plots in the

style of Bloody River Blues, well received by the critics and

readers. The fourth novel by Teri Holbrook, The Mother Tongue, is preceded by

fame in the 90s by the criminal series revolving around the historiographer

Gayle Grason (A Far and Deadly Cry, The Grass Widow

and Sad Water), who researches murders in England and later in her

Georgia home. The Uruguayan-Cuban also competed against Dead of Winter, by P.J.

Parrish, whose editors were sure of leaving with the Edgar prize. Parrish

created a famous personage, detective Louis Kincaid. And last but not least

important was Straw Men, by Martin J. Smith who is proud to be a preceded by

Raymond Chandler and whose novel was praised by James Elroy (author of

L.A. Confidential) that combines perfect intrigue, action and

character.” Chavarría and Cuban literature can proclaim a prize that included

Chandler (The Long Good-bye, 1954), John Le Carré (The spy who came

in from the cold, 1965) and Frederic Forsyth (The day of the

Jackal, 1972).

Granma Daily

September 7, 2002

Daniel Chavarría defrosts the iceberg

By: Antonio Paneque Brizuela

A CubaNews translation by Ana Portela.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2002/09/07/cultura/articulo04.html

In true Hemmingway mystique about one eighth of an iceberg is above the surface

and the other seven eighth submerged. It seems that the iceberg is defrosted in

the novel Adiós muchachos by an author who "fills" brief pages with a

synthesis of a culture where the academic is mixed with the mundane without

touching on encyclopedias and barrio skirmishes that may hide - "under water" -

his particular language.

Of course, this may not have been the intention of Daniel Chavarría when he

wrote the original version (written in only 32 days and later improved) that was

awarded the U.S. Edgar prize in the style of Raymond Chandler one of the

great winners. Although Chavarría was close with his Allá lejos that won

him the Gijon Dashiel Hammett in 1992.

It is difficult to imagine a narrative of such a simple structure, unparalleled

metaphorical paragraphs, all set down in regular syntaxes (perhaps mistakenly

common sentence structure of subject-verb-complement), forms of expression and

semantics of global reach and an empathic flavor capable of exiting us and make

us think: "How I understand you, Chavarría"!

Of course, this is not limited to only this piece in his large repertoire (we

should not forget The perfume of Joy) but, in truth, we expected a crushing

erudition, Latin, Germanic, Gallic terms and all foreign language flavor (if we

ignore the coherent phrases in English, that are also translated) and rhetorical

complexity of a top quality artist, of high education, former university

professor of Latin and Greek.

But take care; it is no longer news in modern times to write the complex simply;

"it is difficult to write simply".

On the other hand, a more profound analysis of the book - not appropriate with

the space we have - would reveal a broader explanation and more prolific details

of virtues (or defects). For a quick reader it is easy to say that the novel is

a page-turner according to those who have read it. Among these is the Spanish

journalist, José M. Martín, who recently made the first presentation of Adiós

muchachos in Havana after the decision, last May, of the Mystery Writers of

América.

Martin explained that the novel has "at least four or five ingredients required

for the genre (detective, black or adventure): a good story, real dialogues, a

dose of humor, a bit of sex and a great dose of tenderness. The dialogue in this

book, truly, is a form of expression that recalls Hemmingway and the slang

language of the detective stories of Chandler and Hammett.

"Adiós

muchachos is as transparent as crystal" said Lesyani Sobrado, when she read it.

"I had read all the translations of the novel - Chavarría commented - but I

hadn't read it again in Spanish from 1995-97. Doing it again, I was actually

surprised. That little novel isn't bad at all. There is a Latin saying that:

"Books pave there own future", because, sometimes, it goes beyond the intentions

of the author. And that is what has happened with this book".

http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2002/09/07/cultura/articulo04.html

Daniel Chavarría descongela el iceberg

Antonio Paneque Brizuela

La

mística teoría hemingweyana de la octava parte del iceberg ("arriba") y otras

siete apoyando ("abajo") parece haber sido descongelada en la novela Adiós

muchachos por un autor que "llena" sus breves páginas con la síntesis de una

cultura donde se mezclan lo académico y lo mundano, pero sin que apenas se noten

las enciclopedias y escaramuzas de barrio que pudiera ocultar —"bajo el agua"—

ese lenguaje suyo a tiro de pistola para cualquier bañista.

La

mística teoría hemingweyana de la octava parte del iceberg ("arriba") y otras

siete apoyando ("abajo") parece haber sido descongelada en la novela Adiós

muchachos por un autor que "llena" sus breves páginas con la síntesis de una

cultura donde se mezclan lo académico y lo mundano, pero sin que apenas se noten

las enciclopedias y escaramuzas de barrio que pudiera ocultar —"bajo el agua"—

ese lenguaje suyo a tiro de pistola para cualquier bañista.

Claro que no tiene que haber sido necesariamente esa

la intención de Daniel Chavarría al concebir su versión original (escrita

inicialmente en solo 32 días y luego mejorada) de esta obra ganadora ahora en un

certamen estadounidense como el Edgar con antecedentes de linaje a lo

Raymond Chandler, uno de sus ganadores colosales. Aunque Chavarría ya picaba

cerca desde antes, mediante su Allá lejos, que le granjeó el Dashiel

Hammett en Gijón (1992).

No resulta simple concebir una narrativa de

estructura tan sencilla, párrafos de metáforas sin élite, todo afincado en la

sintaxis regular (quizás erróneamente preterida por su "simplón" camino

sujeto-verbo-complementos), formas de expresión y semántica al alcance de todos

y un sabor a empatía capaz de extasiarnos y hacernos pensar: "¡Cómo te comprendo,

Chavarría!".

Naturalmente que ello no se reduce solo a esta pieza

de su extensa novelística (nunca olvidemos el perfume de Joy), pero la

verdad es que en esta se queda uno esperando la aplastante erudición, los

latinazgos, germanismos, galicismos y todo olor a lengua extranjera (si

exceptuamos las coherentes frases en inglés, por demás traducidas) y complejidad

retórica que se sobreentendería debiéramos esperar de un creador de alta calle,

pero de elevada escuela, ex profesor universitario de latín y griego.

Pero cuidado, ya no es noticia en los tiempos

modernos concebir lo complejo que es escribir sencillo. Igual a:

lo difícil que es escribir fácil.

Por lo demás, un análisis más a fondo de la obra —excluido

ahora por el espacio— revelaría una explicación menos exigua y un inventario más

prolífico de virtudes (o defectos). Para el lector apurado baste añadirle que la

novela se lee irremisiblemente "de un tirón", en lo cual coinciden todos los que

han podido adquirirla, incluido el periodista español José M. Martín, quien

recientemente hizo la primera presentación de Adiós muchachos en La

Habana después de publicado en mayo último el dictamen de la Mystery Writers of

América.

Martín apreció en esta novela "por lo menos cuatro o

cinco ingredientes que deben exigírsele a este género (policíaco, negro, o de

aventuras): buena historia, diálogos auténticos, dosis de humor, buena dosis de

sexo y una gran dosis de ternura". El empleo del diálogo es en esta obra, por

cierto, otra de las cargas expresivas que la acercan a Hemingway y recuerdan el

filo coloquial del policíaco en Chandler y Hammett.

"Adiós muchachos es transparente como un

cristal", nos decía, por su parte, Lesyani Sobrado, una lectora de ocasión.

"He leído todas las traducciones que han hecho de la

novela —comenta el propio Chavarría—, pero no la había vuelto a leer en español

desde los años 1996-97. Y, al volverlo a hacer ahora, la verdad es que me

sorprendió. No está mala la novelita. Dice un viejo aforismo latino: 'Los libros

tienen su propio destino', porque a veces van más allá de las intenciones del

autor. Y con este libro ha pasado eso."

|

Misterios e iluminaciones del Premio

Edgar de Chavarría

Un momento excepcional para el policial

latinoamericano en Estados Unidos

Pedro de la Hoz

Unos se habrán sorprendido, otros no. Que una obra de Daniel

Chavarría, Adiós muchachos, haya sido proclamada como

ganadora del Premio Edgar 2002 como la mejor novela original en

formato popular (best original paperback) quizá pueda causar asombro

en los medios literarios anglosajones, debido a que nunca antes un

texto de autor latinoamericano había logrado irrumpir en una puja

reservada para los que escriben en la lengua de Poe. Pero para los

que han seguido la trayectoria de este uruguayo radicado en Cuba

desde hace tres décadas, tan aplatanado que su escritura no se

concibe si no es como parte de la nuestra, no existe la más mínima

sombra de dudas acerca de su plenitud como uno de los narradores más

intensos y singulares de la literatura policial o criminal.

Unos se habrán sorprendido, otros no. Que una obra de Daniel

Chavarría, Adiós muchachos, haya sido proclamada como

ganadora del Premio Edgar 2002 como la mejor novela original en

formato popular (best original paperback) quizá pueda causar asombro

en los medios literarios anglosajones, debido a que nunca antes un

texto de autor latinoamericano había logrado irrumpir en una puja

reservada para los que escriben en la lengua de Poe. Pero para los

que han seguido la trayectoria de este uruguayo radicado en Cuba

desde hace tres décadas, tan aplatanado que su escritura no se

concibe si no es como parte de la nuestra, no existe la más mínima

sombra de dudas acerca de su plenitud como uno de los narradores más

intensos y singulares de la literatura policial o criminal.

El Edgar Allan Poe es un premio de

antiguo linaje, auspiciado por la Asociación (Norte) Americana de

Escritores de Misterio (con sede en Nueva York), que comenzó

concediéndose más de medio siglo atrás a obras literarias, tanto de

ficción como testimoniales y estudios crítico-biográficos, y en la

actualidad abarca la producción televisual y cinematográfica.

Para llegar al Edgar se requiere vencer

una travesía parecida a la de otros premios norteamericanos como el

Oscar (cine), el Grammy (disco) y el Tony (teatro). Escritores,

críticos y periodistas votan para nominar cinco obras en cada una de

las doce categorías —la nominación implica, por sí misma, un empujón

publicitario notable— y luego vuelven a votar por el galardón.

También la junta directiva otorga premios honorarios en el campo de

la edición y la promoción, el más importante de todos, el Special

Award, que pone de relieve la contribución de por vida, que en esta

ocasión fue a parar al cineasta Blake Edward, conocido entre

nosotros por su serie de películas sobre La Pantera Rosa

La categoría en que primero fue nominado

y después premiado Chavarría se diferencia de la de Mejor Novela en

atención a términos técnicos editoriales: unos textos se publican

mejor encuadernados y son, por tanto, más caros, y otros en

ediciones populares o bolsilibros, como fue el caso de la puesta en

circulación de Adiós muchachos por Akashic Books en el 2001.

Esta editorial logró un éxito sin precedentes con la historia del

cubano, muy comentada por la crítica por su ingenio y humor en la

descripción de los avatares de una prostituta que opera en bicicleta

en La Habana de los años más arduos del período especial.

Los contendientes de Chavarría son todos

pesos pesados en la literatura policial norteamericana: Hell's

Kitchen lleva la firma de William Jefferies (seudónimo de

Jeffery Deaver), cuyas tramas de horror, al estilo de Bloody

River Blues, se cotizan bien por la crítica y los lectores. La

cuarta novela de Teri Holbrook, The Mother Tongue, está

precedida por la fama levantada a lo largo de los 90 por la serie

criminal de la autora que gira en torno a la historiadora Gayle

Grason (A Far and Deadly Cry, The Grass Widow y Sad Water),

que investiga asesinatos en Inglaterra y luego en su Georgia natal.

El uruguayo-cubano también se las vio con Dead of Winter, de

P.J. Parrish, a quienes sus editores daban ya por seguro ganador del

Edgar. Parrish creó un personaje famoso, el detective Louis Kincaid.

Y no por último, menos importante, fue la concurrencia en las

nominaciones de Straw Men, de Martin J. Smith, quien se

siente orgulloso de que lo inscriban en la estirpe de Raymond

Chandler y cuya novela fue elogiada por James Ellroy (autor de

L.A. Confidential), al decir que "combina a la perfección

intriga, acción y carácter".

Chavarría, y la literatura cubana,

pueden blasonar de un premio que cuenta entre sus ganadores al

propio Chandler (El último adiós, 1954), John Le Carré (El

espía que llegó del frío, 1965) y Frederic Forssyth (El día

del Chacal, 1972).

========================

Adios Muchachos is about jineterismo.

Here's a comment on this from the BBC:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/4749591.stm |

La

mística teoría hemingweyana de la octava parte del iceberg ("arriba") y otras

siete apoyando ("abajo") parece haber sido descongelada en la novela Adiós

muchachos por un autor que "llena" sus breves páginas con la síntesis de una

cultura donde se mezclan lo académico y lo mundano, pero sin que apenas se noten

las enciclopedias y escaramuzas de barrio que pudiera ocultar —"bajo el agua"—

ese lenguaje suyo a tiro de pistola para cualquier bañista.

La

mística teoría hemingweyana de la octava parte del iceberg ("arriba") y otras

siete apoyando ("abajo") parece haber sido descongelada en la novela Adiós

muchachos por un autor que "llena" sus breves páginas con la síntesis de una

cultura donde se mezclan lo académico y lo mundano, pero sin que apenas se noten

las enciclopedias y escaramuzas de barrio que pudiera ocultar —"bajo el agua"—

ese lenguaje suyo a tiro de pistola para cualquier bañista. Unos se habrán sorprendido, otros no. Que una obra de Daniel

Chavarría, Adiós muchachos, haya sido proclamada como

ganadora del Premio Edgar 2002 como la mejor novela original en

formato popular (best original paperback) quizá pueda causar asombro

en los medios literarios anglosajones, debido a que nunca antes un

texto de autor latinoamericano había logrado irrumpir en una puja

reservada para los que escriben en la lengua de Poe. Pero para los

que han seguido la trayectoria de este uruguayo radicado en Cuba

desde hace tres décadas, tan aplatanado que su escritura no se

concibe si no es como parte de la nuestra, no existe la más mínima

sombra de dudas acerca de su plenitud como uno de los narradores más

intensos y singulares de la literatura policial o criminal.

Unos se habrán sorprendido, otros no. Que una obra de Daniel

Chavarría, Adiós muchachos, haya sido proclamada como

ganadora del Premio Edgar 2002 como la mejor novela original en

formato popular (best original paperback) quizá pueda causar asombro

en los medios literarios anglosajones, debido a que nunca antes un

texto de autor latinoamericano había logrado irrumpir en una puja

reservada para los que escriben en la lengua de Poe. Pero para los

que han seguido la trayectoria de este uruguayo radicado en Cuba

desde hace tres décadas, tan aplatanado que su escritura no se

concibe si no es como parte de la nuestra, no existe la más mínima

sombra de dudas acerca de su plenitud como uno de los narradores más

intensos y singulares de la literatura policial o criminal.