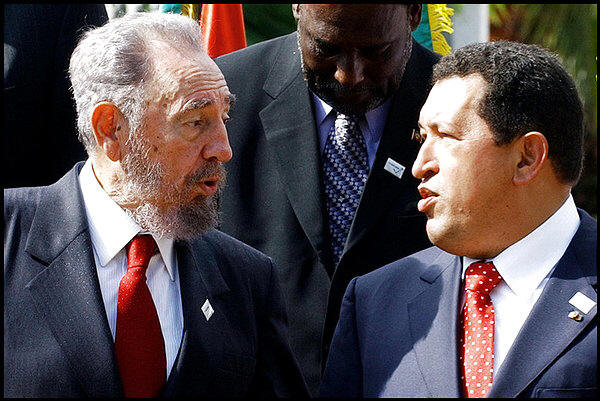

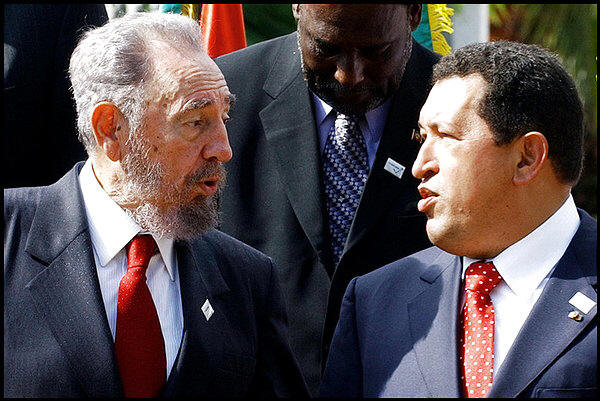

Fidel Castro, left, with Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez during a visit

to Venezuela last month. Chavez often speaks admiringly of Cuba's president.

Most Venezuelans Prefer Socialism

Caracas, Jul 15 (Prensa Latina) With a social policy favoring the majority, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez is successfully achieving his goal of ending prejudice against socialism in the country.

The president disclosed a poll Thursday revealing 47.9 percent of Venezuelans favor a socialist government, 25.7 percent support capitalism, and 24.6 percent did not answer the question.

The survey was done last May 26-June 9 by a private enterprise, and Chavez said although most of Venezuelans prefer socialism over capitalism, the number of undecided people is still high. He called for a continuous ideological offensive "to defeat ghosts."

The Venezuelan president, a self-declared socialist, reiterated in his regular talks with the population that socialism is the only way to overcome privatization, poverty, and a backward state.

Chavez said his government plans to give "course to a new socialism" as a way to solving inherited problems.

Regarding this, he encouraged Venezuelan society to openly debate for the creation of what he has defined as Socialism of the 21st Century, while still supporting programs already implemented.

ln/dig/ml/mf

Chavez touts `21st Century Socialism'

http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/chi-0507150124jul15,1,7753900.story

Chavez touts `21st Century Socialism'

Venezuelan leader plants projects for workers to manage Advertisement

By Gary Marx Tribune foreign correspondent

July 15, 2005

CIUDAD GUAYANA, Venezuela -- Standing before a group of nascent entrepreneurs, Carlos Lanz looked less like a former communist guerrilla than an aging university professor as he laid out the next phase of Venezuela's revolution.

Aiming a light pointer at graphics projected on a large screen, Lanz--who long ago laid down his weapon but not his ideals--outlined Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez's plans for transforming this oil-rich nation into something approaching a workers' paradise.

"Venezuela suffers a distortion because many of us are excluded from production, from wealth and services," said Lanz, 62, a key architect of Chavez's reforms. "We are constructing a new economic model."

The road so far has been rocky. Faced with violent protests and a bitter recall referendum, Chavez spent his first six years in office fighting for his political life even as he poured billions of dollars into social programs.

But now, with the political opposition vanquished and oil prices near record highs, the Venezuelan leader is in a strong position to launch what he describes as "21st Century Socialism."

Eschewing Marxism-Leninism, Lanz says, Chavez has developed an economic model called "endogenous development" whereby state oil money will finance the creation of thousands of small-scale cooperatives in agricultural and other areas to provide jobs and foster community development.

A second leg of Chavez's master plan is something known as "cogestion," roughly translated as co-management, where the state is helping workers purchase shares of companies they work in to give them a greater say in management.

The goal of all this, they say, is to lift millions out of poverty by reducing Venezuela's reliance on oil, which has left the country with a weak manufacturing and agricultural base and over-dependent on imports of food and almost everything else.

Managers are elected

"We hand over cheap raw material to The Empire [the United States] and the multinational corporations, and they sell us very expensive goods," said Lanz, who describes the nation's business elite as a "parasitical oligarchy." "So who benefits? People in the North."

The son of a wealthy farmer who became a leftist rebel in the 1960s, Lanz is using cogestion to revamp CVG Alcasa, an obsolete state-owned aluminum plant in this scorching city about 330 miles southeast of the capital, Caracas.

The key change Lanz has implemented in his three months at the helm is allowing workers to elect their own managers, the first step, he and others say, to improving efficiency.

"Now decisions are not made by one person in an office," explained Alcides Rivero, a 23-year Alcasa employee, as he walked past huge stacks of aluminum ingots. "Now decisions are made around a table. We elect who will direct us. It's not imposed from the top."

Critics say electing managers is fine but it won't lift an uncompetitive plant like Alcasa out of the red. They say Chavez's economic plan resembles the import-substitution polices that were tried with limited success in Latin America decades ago.

"This is nothing new," said Teodoro Petkoff, editor of Tal Cual, a respected Caracas newspaper critical of Chavez. "This is a project that has short legs."

Whether Chavez succeeds or fails in his economic gambit could have enormous impact across the continent, where the Venezuelan leader is gaining influence amid a resurgence of the Latin American left.

The outcome also is crucial to the United States, which imports large quantities of Venezuelan oil despite Washington's hostility toward Chavez and Chavez's anti-Americanism.

The former army paratrooper first came to national prominence leading a failed coup in 1992. He was elected president six years later and, after changing the constitution, re-elected in 2000, surviving a brief but bloody coup, a devastating opposition-led national strike and last August's presidential recall referendum. In that contest, he won with a decisive 59 percent of the vote after many had predicted his downfall; the United States had helped fund several opposition groups.

Today, many of Chavez's most vocal critics have either left the country or are relegated to the inside pages of newspapers.

The president and his allies control the National Assembly, 22 of 24 state governorships, the Attorney General's Office and the Venezuelan Supreme Court.

Chavez supporters also form a majority in the National Electoral Council, which will oversee presidential elections next year.

With his approval rating above 70 percent, Chavez is almost certain to win a six-year mandate in 2006 despite critics' assertions that he is a populist demagogue who is undermining Venezuela's democracy.

"They control everything," lamented Petkoff. "There is a serious danger of autocracy."

An engaging personality whose down-home style resonates with many Venezuelans, Chavez's popularity stems in large part from spending billions of dollars on educational programs, subsidized food for the poor and other efforts.

Yet, despite his class-based rhetoric and tightening grip over the economy, Chavez has generally respected private enterprise and business is booming in an oil-fueled economy that grew more than 17 percent in 2004.

On a recent evening, sidewalk cafes and upscale restaurants in Caracas' wealthier neighborhoods were packed with fashionable couples--the kind who last year led street protests against Chavez but now seem weary of the political fight.

But economists and other experts say there are warning signs on the horizon.

Private investment remains low because of uncertainty over Chavez's long-term goals and his feud with the U.S. Then there is the issue of oil prices, which provide a windfall now but could become a liability.

"Chavez is strong. Chavez is popular. And Chavez has a lot of money," said Luis Vicente Leon, an opposition pollster. "But Chavez knows that he could have trouble in the future."

Chavez has begun a media blitz to sell his new economic plans to Venezuela's 24 million people. Public service spots are appearing on state-run television, and brochures are distributed at work sites.

"Unstoppable Revolution," read a headline in CVG Alcasa's company newspaper.

Making salsa from mangos

In a recent television appearance, Chavez listened to public school students outlining their own ideas for diversifying the economy away from oil, a homework assignment that fit neatly into Chavez's agenda.

The students offered proposals ranging from opening a bakery to produce bread to making wine and salsa out of mangos.

"Do you think this is an important need for the community?" Chavez asked the student making the mango presentation.

"I think so because otherwise they would have to buy an expensive salsa," the student responded. "This is much more economical and it's a product that is native to our region."

"It's true that we have tons of mangos that go to waste," Chavez said. "This is a good idea."

Antonio Frausto, a state oil company worker who is overseeing about two dozen endogenous projects, acknowledged that many of them are in their early stages or remain on the drawing board.

The ideas range from organizing a cooperative to manage a new milk production plant to helping Warao Indians set up a market to sell baskets, hammocks and other products to tourists.

"We have a lot of plans and a lot of money, but the plans are not completely linked," Frausto said. "It's like changing a tire when the car is moving."

One model for Chavez's new economy sits on a hill overlooking Catia, a working-class neighborhood in Caracas.

There, the government spent about $3 million to build a shoe factory and clothing factory employing about 400 people. The project includes a health clinic and basketball court.

Inside the clothing factory, several dozen women belonging to a new cooperative sat at sewing machines making aprons, sweatpants and other items.

The government is providing the employees an interest-free loan, technical support and other assistance to get them started and has been paying each employee a $90 monthly stipend.

"This is a source of work for the neediest," said Ana Guedez, a 39-year-old former homemaker who now works as a seamstress. "We are just starting out."

But Frausto, who manages the Catia project, said it is uncertain whether the factory's production and quality will ever be high enough to ensure its long-term viability.

"If the cooperatives are not competitive, they will survive as long as we have petro-dollars or as long as the government survives," he said.

----------

gmarx@tribune.com

Copyright © 2005, Chicago Tribune

Fidel Castro, left, with Venezuelan

President Hugo Chavez during a visit

to Venezuela last month.

Chavez often speaks admiringly of Cuba's president.

Venezuela Has Oil Money,

And Chavez Sings His Tune

By Monte Reel

Washington Post Foreign Service

Friday, July 15, 2005; A01

CARACAS, Venezuela -- Standing before a battery of television cameras, President Hugo Chavez confronted the impulse to break into song and -- as often happens in such moments -- surrendered without a fight.

" Guantanamera ," he sang in confident baritone, swaying slightly to the refrain of Cuba's most celebrated tune. " Guajira Guantanamera . . . ."

Chavez was in the middle of his weekly six-hour television program, "Hello, President," which during 228 episodes has provided exhaustive insight into the man who rivals Fidel Castro as Latin America's most charismatic and controversial leader.

The Cuban love song was a fitting soundtrack for a recent episode, in which Chavez repeatedly thanked Castro for inspiring him to accelerate the redistribution of wealth in a nation where about half the people live in poverty.

Riding on a tide of record prices for Venezuelan oil, Chavez -- who has survived both a brief coup and a recall referendum -- now appears to be consolidating public support, using the economic windfall to expand social programs for the poor and to intensify what he calls a "peaceful revolution" against global capitalism.

Chavez's political relations with the United States remain as rocky as ever, and he has repeatedly asserted that the CIA is plotting to overthrow him. Domestic opponents, meanwhile, charge that his new social largess is accompanied by heavy-handed attempts to take control of the country's institutions and stifle dissent -- all in an effort to hold on to power as tightly as his hero in Havana has done for 46 years.

"He's making all sorts of changes, and he's doing it on the advice of Fidel," said Carlos Eduardo Berrizbeitia, a legislator from a political party opposed to Chavez. "He now has begun tailoring the institutions in this country -- like the Supreme Court -- to create a suit that fits only himself. The suit has the sheen of democracy, but it's not real."

With sales of 1.5 million barrels of oil a day to the United States, worth as much as $2.7 billion a month, Chavez has increased government spending by 36.2 percent this year. He has poured billions into state-subsidized grocery stores, workers' cooperatives, adult education centers and public health clinics staffed by what government officials say are about 16,000 physicians on loan from Cuba.

Meanwhile, the president has persuaded the friendly National Assembly to allow him to replace opponents on the Supreme Court, fill a dozen extra judicial seats with allies, revamp the national penal code and tighten controls on TV and radio broadcasters. In addition, the legislature is poised to give him greater control over Central Bank reserves.

The government declined requests for an interview with the president.

While critics at home and abroad warn of his increasingly dictatorial tendencies, Chavez enjoys broad support among the poor and popularity ratings exceeding 60 percent. When fans watch him on television, they don't see a power-hungry demagogue, but a defiant ally who sings when he feels like it and doesn't care if detractors say they've heard the tune somewhere before.

"They talk about human rights abuses, they say that Chavez is a tyrant and a dictator," Chavez said during his show. "They are lies, all lies."

Persistent Poverty

Thousands of shoppers shouldered their way through the streets of Petare, a gritty neighborhood in eastern Caracas, dodging rain-filled potholes. Vendors under grimy umbrellas hawked virtually everything from diapers to rat traps.

Almost all the buyers and sellers were poor, or close to it. But few of them blamed Chavez for their plight.

"He's done what no other president has done before," said Carlos Romero, 49, a truck driver in a torn T-shirt and jeans. "He helps poor people."

"And he's keeping Venezuela independent," interjected Rafael Villalba, 42, who sells herbs from a street-side table. "Venezuela is the most democratic country in Latin America. You can do whatever you want here. You can say anything you want about anyone."

A crowd gathered, eager to debate. Two men, drinking beer at an open-air stand, complained that Chavez had not done anything to help them find jobs.

"It's not Chavez's fault!" yelled Viviana Caciani, 33, jumping into the fray. "Long live the revolution!"

Politics is never far from the surface in Chavez's Venezuela, even at a weekend market. On a bag of rice, an article of the Venezuelan constitution had been printed to remind buyers that the government was subsidizing such products.

An accompanying illustration showed a cartoon hero kicking a devil in a business suit -- an imperialist villain chased by a government representative who, the caption said, was guaranteeing the public's "nutritional security."

But other forms of security are harder to come by in Caracas. Despite the flowing oil revenue, crime is rampant and destitution is never far off. Some Venezuelans wonder whether Chavez will be able to sustain his current popularity level if the atmosphere doesn't change soon.

"The question everyone asks is, 'If Venezuela is so rich, why am I so poor?' " said Alfredo Keller, a pollster and analyst. "Chavez is trying to introduce profound ideological changes with the inspiration of Castro, and he has begun to advance a debate that says to be rich is bad. But that isn't an opinion many people here share."

Although Chavez rhetorically invokes such communist icons as Karl Marx and Che Guevara, Venezuela is a long way from becoming another Cuba. Billboards for products such as Pepsi and Nescafe help shape the skyline of Caracas, despite Chavez's insistence that Venezuela should free itself from the influence of global capitalism. This month, the government hosted more than 200 U.S. companies at a trade fair intended to expand and diversify bilateral business ties.

So far, the economic trends since Chavez took office in 1998 have been mixed. Unemployment in May was at 12.6 percent, 3 points lower than the same time last year, but 53 percent of households lived in poverty in 2004, compared to 49 percent six years ago, according to government data.

The president's supporters say the figures do not reflect recent increases in public spending, which have given people on limited incomes greater buying power. At one of the state-subsidized markets Chavez has opened nationwide, people lined up on a recent day to buy large bags of pasta for 50 cents and boxes of Kellogg's Corn Flakes for about $1.30.

Sujey Escobar, 29, a maid with two children and an unemployed husband, left the store carrying bags of rice, flour and salami that she estimated would have cost about twice as much at a regular market.

"It's still hard to find work," she said, "but buying groceries is a little bit easier."

Changes for Mass Media

Patricia Poleo slipped off her headphones and stepped out of the booth where she broadcasts the top-rated AM radio program in Venezuela. A veteran newspaper editor and commentator, she is an outspoken critic of Chavez. She is also facing a six-month prison sentence for defaming the interior minister.

"The government is trying to intimidate the media," said Poleo, 39. "And some journalists are following their orders because of the new fines that they could pay."

Poleo was referring to the Law of Social Responsibility in Radio and Television, a revised list of standards for broadcasters that was passed last year and currently is being phased into practice. With that, and stiffened libel and slander laws, Poleo and some other journalists say they believe that Chavez is trying to snuff out criticism before it starts.

The changes are ostensibly designed to protect children from sexual and violent programming and encourage more variety on the airwaves. The standards now require three hours daily of children's programming and seven hours of nationally produced programming.

But some observers fear the law's instructions to ensure national security and promote Venezuelan cultural values could be interpreted broadly by a judicial system increasingly aligned with Chavez. Some critics said they already have noticed self-censorship among government critics and sponsors, who can also be fined.

Poleo said that instead of being able to sign a deal directly with the radio station where she works, she will soon be assigned a station by the government and fears she might end up with a pro-government boss.

"The idea is to force people off the air," she said.

The government insists that changes were necessary after some media outlets openly supported the 2002 coup. Instead of discouraging diversity of opinion, they say, the law explicitly guarantees it.

"All of the criticism of the law is based on supposition," said Desiree Santos Amaral, who heads the legislature's communications committee. "All of the criticism being disseminated about the law is proving that it works."

One outlet assured of getting its message across is state-run television, where Chavez broadcasts his Sunday show. Last week he broadcast from one of the education centers that he said was helping to wipe out illiteracy -- "thanks to Fidel" and the loan of Cuban social workers.

Chavez interrupted his monologue to listen to newly literate audience members read passages from the national constitution, then continued extolling the virtues of his social policies.

"The revolution marches on," he concluded several hours later, signing off with a smile.

© 2005 The Washington Post Company

(More good

news from the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela:

"Every time Condoleezza Rice attacks Chavez, his approval

rating goes up 2 or 3 percentage points," said Luis Vicente Leon,

a pollster and Chavez critic.)

==========================================================

Venezuela uses oil sales,

army buildup to defy U.S.

By Gary Marx

Tribune foreign correspondent

Published July 15, 2005

LOS ALTOS MIRANDINOS, Venezuela -- As military officials barked orders, more than 300 civilians gathered in the morning hours to practice saluting and precision marching in preparation for possible war.

There were homemakers and retirees, lawyers and street vendors, all volunteers of a newly expanded army reserve force that President Hugo Chavez is organizing to defend the country against the United States and other threats.

"The United States is the only superpower, but if the people are united we can defeat them," said Arnaldo Cerniar, a 65-year-old retired credit officer who began training three months ago. "We need to defend the country against any aggression."

Chavez's recent decision to expand Venezuela's reserve force to as many as 2 million people is only one indication of the growing tensions between this oil-rich nation and the U.S. Although Venezuela continues to sell large quantities of oil to the United States, Chavez has threatened to cut off supplies in the event of an American invasion. U.S. officials have dismissed the idea of a military attack on Venezuela.

Nonetheless, Chavez is seeking to diversify crude-oil sales away from the U.S. and has reoriented Venezuela's foreign policy toward its Latin American neighbors and other nations, such as Iran. Chavez recently signed a pact with 13 Caribbean nations to sell them discounted oil and has pushed oil and gas accords with South American nations to counter U.S. power in the region.

So far, U.S. efforts to isolate Chavez diplomatically have failed.

At a recent meeting of the Organization of American States, the U.S. couldn't muster enough support to set up a permanent committee to monitor democracy in the region, a proposal that was widely interpreted as aimed at Venezuela.

William LeoGrande, dean of the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington and an expert on Latin America, said OAS members rejected the measure because Chavez is democratically elected and because the U.S. is disliked in a region where free-market measures have failed to ease poverty.

He said the OAS failure leaves the U.S. with few options to contain Chavez.

"The problem the administration has is that there are not many levers the U.S. can use," LeoGrande said. "As a principal supplier of oil, Venezuela is still commercially important to the U.S."

Many argue that the U.S. criticism has allowed Chavez to benefit politically by playing the nationalist card.

"Every time Condoleezza Rice attacks Chavez, his approval rating goes up 2 or 3 percentage points," said Luis Vicente Leon, a pollster and Chavez critic.

Copyright

C 2005, Chicago Tribune

washingtonpost.com

Some of Cuba's Doctors Work in Venezuela

The Cuban doctors Ismeldo Cubas,

right, Salvador Amador, center, and Azalea Blanco practice an endoscopy

examination to a Venezuelan soldier at a humanitarian mission "Barrio adentro"

medical center inside of the military base of Fort Tiuna in Caracas, Venezuela,

Wednesday, June 15, 2005. Cuba's communist government is expanding a

humanitarian mission that has already sent a fifth of the island's doctors to

work in Venezuela, committing more aid to its close ally as Cuba receives

massive shipments of Venezuelan oil. (AP Photo/Fernando Llano)

By IAN JAMES The Associated Press Wednesday, July 13, 2005; 2:54 AM

LOS POTOCOS, Venezuela -- Amid the rows of shacks inhabited by poor farmers and unemployed laborers, doctors in white coats now make house calls, dodging children running barefoot and chickens pecking at piles of trash.

Those doctors _ on loan from Cuba _ are a welcome sight in this dusty village and other forlorn corners of Venezuela where physicians seldom set foot.

Cuba's communist government is expanding a humanitarian mission that has already sent a fifth of the island's doctors to work in Venezuela, committing more aid to its close ally as Cuba receives massive shipments of Venezuelan oil.

"Thank God those doctors are here," said Maria Aray, 50, who said the Cubans helped her 14-year-old daughter recover from severe anemia.

The Venezuelan government says the program involves about 20,000 Cubans, including more than 14,000 physicians _ an estimated 20 percent of Cuba's doctors. Cuban President Fidel Castro has pledged to have up to 30,000 health care workers in Venezuela by the end of the year.

Castro has long sent doctors on missions to countries ranging from Haiti to Equatorial Guinea _ always treating the poor for free _ but Venezuela in recent years has become their top destination.

In turn, Venezuela ships Cuba 90,000 barrels of oil a day under preferential terms, a deal giving the island one of its strongest economic boosts since the fall of the Soviet Union. Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez says the medical mission is unrelated to the oil deal.

But so many doctors have gone to Venezuela that some Cubans complain health care on the island is suffering. Castro insists they are mistaken, and that there are enough doctors to go around. Both countries, he says, are reaping the benefits of cooperation.

Chavez, who describes Castro as his mentor, calls the program part of a "war to save lives" as Venezuela moves toward socialism, and he says the benefits are clear. In addition to the visiting doctors, thousands of Venezuelans have been flown to Cuba to undergo surgery for free.

In Los Potocos, 150 miles east of Caracas, the three Cuban doctors see their presence as vital for poor patients who can't afford even basic medicines.

"This is the first time I've left Cuba, and I've never seen anything like this," said Dr. Leonardo Hernandez, 27, checking the pulse of a 2-month-old boy in a home where wires dangled from light fixtures and concrete walls were covered in grime.

When he and his colleagues arrived two years ago, they found malnourished children and widespread diarrhea. Now, they say, vitamins are making the children healthier, and there have been vast improvements in sanitation.

Some critics accuse Chavez of using the Cubans to maintain political support while neglecting public hospitals that have outdated equipment and shortages of supplies from needles to surgical thread.

The government has pledged to fix or replace old hospitals, but some Venezuelan doctors say Chavez is instead creating a parallel health system. The Venezuelan Medical Federation has urged its members to protest in Caracas on Friday to demand pay raises and oppose the Cubans' "illegal" practice of medicine in the country.

"We don't need them at all. What we need is a coherent health policy," said the federation's president, Dr. Douglas Leon Natera.

Chavez has called the Cuban medical mission the best hope for improving care for the poor, and has urged more Venezuelan doctors to join. His government has begun training thousands of new doctors.

Some accuse Venezuelan doctors of treating the wealthy while ignoring the hillside slums of Caracas.

"Why don't they come up here into the hills?" said Dr. Marta Diaz, a 43-year-old Cuban who for two years has been offering acupuncture along with traditional medicine.

Diaz said she would gladly stay as long as needed, even though it keeps her apart from her husband and two daughters.

Doctors who accept an invitation to work in Venezuela receive an extra stipend of $186 a month from the Venezuelan government, while Cuba continues to pay their families their regular salaries, commonly in the range of $25 a month.

Otto Sanchez, a Cuban doctor who defected in 2003, said he felt he was being used for a "political program."

"You realize that you're being exploited with the kind of salary you're paid," said Sanchez, 38, who complained doctors were given pamphlets to hand out praising Cuba's medical system.

Sanchez now lives in Miami, where he is part of a group that has helped more than 20 Cuban doctors desert their posts in Venezuela.

But Hernandez said he doesn't understand how doctors can leave when they are so badly needed.

"It's like betraying oneself as a doctor, as a person," Hernandez said. "What we're doing here is something too beautiful to stop."

___

AP correspondent Andrea Rodriguez contributed to this report from Havana, Cuba.

© 2005 The Associated Press

Che Guevara's Daughter Writes Chavez Bio

By Andrea Rodriguez

The Associated Press

Monday, July 4, 2005; 1:04 AM

HAVANA -- Revolutionary fighter Che Guevara's daughter has written a book about Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez based on interviews in which they discussed his childhood, family and relationship with Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

"It is always thrilling to know a bit more about a human being who has decided to transform society, especially when that transformation is meant to improve the lives of his people," Aleida Guevara wrote on the book's back cover.

The book, published by Ocean Press and titled "Chavez: Venezuela and the New Latin America," was presented in Havana Friday by the author and Adan Chavez, Venezuela's ambassador to Cuba and also the president's brother.

Guevara met with Chavez twice in February of 2004 in Caracas, Venezuela for the interview. In the 145-page book, the president talks about his childhood in the southwest region of Barinas, where he was born in 1954, and his close relationship with his grandmother Rosa Ines, who raised him.

The Venezuelan leader also speaks openly about his children, his political life and his friendship with Castro.

"Those who have tried to damage my personal or political image for the special relationship I have with Fidel don't realize that they've only given it more power," Chavez says in the book.

Chavez, who is a close ally of the Cuban president, says Castro is like an older brother _ a father even _ with whom he discusses ideas and receives health advice.

The book has a personal touch because the author's father Che Guevara and Castro were brothers-in-arms in the Cuban revolution and looming icons of the left in Latin America and around the world.

Distribution of the book has begun in English in the United States and Great Britain, and in Spanish in Venezuela and Argentina, according to Ocean Press. It will be released in Ecuador shortly.

___

On the Net: