The following account is from an interview with the author on July 23 and 24, 2008, with material from an interview with Rosa Elizalde and Luis Baez published in Los Disidentes (Editora Política, 2003).

![]()

![]()

![]()

The following account is from an interview with the author on July 23 and 24,

2008, with material from an interview with Rosa Elizalde and Luis Baez published

in Los Disidentes (Editora Política, 2003).

Spy vs. spy Cuban dissidents march to orders of US

by Diana Barahona

First published in Spanish in La Republica:

http://www.larepublica.es/spip.php?article11967

Aleida Godínez worked for the Cuban intelligence services as an undercover agent from 1991 until 2003, when she became a star witness at the trials of 75 individuals arrested for working on behalf of the United States as dissidents. A prominent dissident herself, Godínez spent years insinuating herself into the world of the hired opposition, proving herself a loyal and capable employee of the U.S. Interests Section and the CIA in Havana.

From her humble beginnings as a human rights activist in her native Ciego de Ávila, Godínez went on to become an independent journalist, and independent librarian, founder of the Cuban Christian Democratic Party, a leader of two independent labor organizations, the right hand of Martha Beatriz Roque, a trusted spy of a CIA officer and a close friend of Frank Calzón, executive director of the Center for a Free Cuba. All of the titles and organizations were fictitious, and all followed the orders of the US Interests Section.

In her capacity of celebrity dissident Godínez was a guest on Radio Martí, filing 102 reports about supposed human rights violations between 1992 and 1993. She met with diplomats and delegations from several countries, and received copious amounts of money, gifts and free meals. She was tasked with spying for the United States, and carried the required information, gathered by her Cuban handlers, to the American handlers at the USIS.

Through the years, there were but two things that motivated the dissidents: money and visas to the United States. The visa business was a two-edged sword, however; even though the prospect of getting a visa drew people to the movement, they were soon bound for Miami. The dissident payroll was like the workforce at a fast-food restaurant, which meant that the USIS was constantly training new employees. Godínez herself certified a great many applicants. In her interview for Los Disidentes she illustrated the high turnover:

I had 11 people in the delegation of the Cuban Christian Democratic Movement. Out of those, eight were trying to leave the country and, as a matter of fact, they are out of Cuba at this time. Of the other three, I later learned that one was an agent of ours. The same thing was happening with the other movements. The one that had a few more members was the Cuban Human Rights Committee, with some 15 or 20. All of them left the country in those years. (p. 10).

Godínez is a jovial, outgoing woman with a voice that carries. It isn’t hard to imagine her as a counter-revolutionary – not work for the shy and timid. She bragged about being responsible for the Clinton administration beginning to send large sums of money to Cuban dissidents in 1995. The way she tells the story, she was present at a meeting between dissidents and Ann Patterson, Clinton’s undersecretary for Caribbean affairs. When Patterson asked, “What is needed to overthrow Castro’s revolution?” none of the others said anything, so Godínez spoke up. “Well, look,” she said, “when Napoleon was making the war, someone asked him what he needed to win it. He answered that he needed only three things: money, money and more money, and that is what we need as well: money, because if there is no money or resources, nothing can be done.” Soon after that, Clinton met at the White House with Frank Calzón and gave him $500 000.

But the truth is that the sums were only large for the Cuban economy; the lion’s share of the millions of dollars budgeted for Cuba stays in Washington and Miami, as a 2008 report by the Cuban American National Foundation admits.

Godínez made her first contact with the USIS on June 20, 1994. “When a political party is created [the Cuban Christian Democratic Party] that I founded with four others, I present the political party to the Interests Section,” she said. At the USIS she met with Christopher Sibila, who Godínez says made no bones about being a CIA official. Sibila introduced her to his boss, Charles O. Blaha, who approved giving her an unlimited pass to the building. There, she had access to phones, computers and fax machines. But it was the arrival two months later of Robin Diane Meyer that was a turning point in her career.

“Charles O. Blaha recommends to her that she interview me. And from that recommendation – which are very special recommendations because supposedly these people have studied you, they’ve characterized you and they know you – when Robin Diane Meyer arrives in Cuba she considers me practically one of them.”

Meyer had been given the mission of unifying the opposition, and gave herself the title of “godmother of the opposition.” She brought with her a how-to manual, titled Resource Guide for the Transiition in Cuba.” This guide was published by the Committee for the Transition in Cuba of the International Republican Institute, which was headed at the time (1996) by Jeb Bush. Other notable members were Frank Calzón, Pepe Cárdenas (director of the CANF), Ricardo Ofil, Ernesto Betancourt, Elliot Abrams, Lincoln Díaz-Balart, Jaime Fernández, Daniel Fisk, Adolfo Franco (head of USAID until the recent scandal) and Carlos Franco. “But one person who stood out for me the most who was a member of this committee was Porter Goss, who a few years later was the director of the CIA.” Also on the committee were Jeanne Kirkpatrick, Sen. Connie Mack, Otto Reich, Roger Noriega – “a whole series of individuals who have a past that is closely linked to the secret services of the United States,” Godinez said.

In 1995, as part of a recent immigration agreement, Meyer was allowed to travel all over Cuba and she visited Godínez several times in Ciego de Ávila. “From then on she began to give me special treatment. Within that special treatment that she gives me, she suggests that I write to Frank Calzón. She says that there is a group of non-governmental organizations, foundations, that are eager to help the dissident movement in Cuba. And to that end she places in my hands the Resource Guide for the Transition in Cuba.” Godínez called the guide her bible, because she often consulted it to learn how to write and say the things her U.S. sponsors wanted to hear. Godínez met with Meyer more than 100 times in the two years before her expulsion from Cuba in 1996. “This lady, a CIA officer, a very good friend of mine, was the one who put me in contact with Frank Calzón.”

The first executive director of the Cuban American National Foundation, Calzón went on to be a director of Freedom House, a government-funded “democracy promotion” organization with a list of directors that has included prominent neocons such as Donald Rumsfeld, ex-CIA directors, mafia-linked labor leaders and journalists P.J. O’Rourke and Mara Liason.

During the 1990s Calzón was in the habit of sending emissaries to Cuba in the name of Freedom House, to pass out money and conduct espionage. One of his agents, David Norman Dorn, was arrested in August 1997 and confessed to spying on economic targets and contacting Cuban dissidents to deliver money, according to Los Disidentes (p. 24). This was an embarassment for Freedom House, so in October of that same year Calzón took his Freedom House staff and with Otto Reich’s support formed the Center for a Free Cuba, with $200 000 in private funds from expatriates, $400 000 from USAID and $15 000 from the NED. The CFC could also be called Calzón’s cash cow in light of the millions in grants it receives and the meager amounts that actually get to Cuba, and the fact that Calzón associate Felipe Sixto was found to have embezzled $500 000 in April this year.

Godinez said that in 1996 Meyer proposed writing a letter to Frank Calzón at Freedom House telling him what her needs were. “And I, very prudently as I go by the instructions of State Security, write the letter, and I ask him for medicine and literature about human rights; and then I give her the letter, and she tells me, ‘Let’s send it here at the Interests Section through the fax at the Interests Section.’

“She had already given me the number, the book we’re talking about. Frank Calzón was then the director of the Free Cuba program of Freedom House. He had recently received $500 000 from President Clinton to achieve the transition of Cuba – translated into Spanish, for the defeat of the revolution. “I carried that letter to the Interests Section and the curious thing about it was that they didn’t send it. Instead, a few weeks later Frank Calzón calls me at home. My number is not listed in Havana. In other words, evidently there was a link between Robin Meyer and Frank Calzón.” Godinez’s first talk with Calzón marked the beginning of a long relationship. Asked how close their relationship was, Godínez said, “Very good. So good that I used to call him each Sunday at two in the afternoon at his home, every Sunday.”

“Frank Calzón would send me money twice a year – a lot of money.”

She picked up her last payment in March, 2003, right before the 75 dissidents were arrested. At the time, Roque’s group was holding a fake fast for a jailed member, during which they ate hearty soups and gave out visa certifications. Godínez went to the fast, picked up her money, and went out for lunch. The “fasters” were arrested later that day. “And I kept Frank’s money, of course.” Godínez is the same agent who in 1999 met with New York City librarian Robert Kent, introduced to her as Robert Emmet. She says that Calzón couldn’t go to Cuba, so he sent Kent in his place. Kent had made prior trips on behalf of Calzón and Freedom House, but at time of his 1999 trip it is not clear which group was sponsoring him, since Freedom House now claims they never heard of him. Kent arrived in Cuba on Feb. 22, 1999, and made contact with Godínez two days later, on Feb. 24. For security reasons she had a separate house in Havana for meetings. When Kent arrived at the house, she said, he brought a large duffle bag. In it were medications, toiletries, batteries, radios, watches, cameras and a Radio Shack 10-band shortwave radio so the two could keep in contact. Godínez says he gave her a Casio watch with a GPS, the shortwave radio and a cheap Orlando 35mm camera. He bought her some Kodak film.

What Calzón wanted was sensitive information, Godínez said. Kent asked her about petroleum deposits and about a state enterprise that charged tourists for medical services. “The enterprise was called Servimed,” she said. “They wanted to know precisely who the director was and what kinds of services they offered.”

Kent also gave Godínez the task of taking pictures of the security around the house of Carlos Lage Dávila, then president of the Council of Ministers. “He explained to me that the North American government thought that Carlos Lage could be Fidel Castro’s replacement,” she said. “I had to take the photographs at the request of Frank Calzón,” she said. “Frank Calzón was the one who had sent Robert Kent to Cuba, he had financed the trip. “Besides that, he had brought $500 from Calzón to give to me, but Kent felt so comfortable with me that instead of giving me $500 he gave me $700 to buy myself a motorbike,” she said. Asked if this could have been a personal initiative on the part of Calzón, Godínez said she didn’t think so, since her initial contact with Calzón had been made through Robin Meyer. “Curiously, Robert Kent asks for the same sensitive information that Meyer was asking me for: petroleum deposits and Servimed.”

Asked if Kent, the founder of Friends of Cuban Libraries, ever visited a library, Godínez said no. “The Cuban libraries project began in October 1998, and four months later, Kent came to Cuba; but he didn’t bring any books,” she said. “There was only one independent library in Las Tunas, and Kent didn’t go to Las Tunas.” At this point Godínez took out a photo of the independent library she still keeps at her house as a memento of her days as a security agent. It is a small book case full of books and papers. She says that she took Kent around to different dissidents’ houses, where he would ask to use the bathroom and come back with money for them.

Godínez took the photographs she had been asked to take of Lage’s house, and they were seized from Kent at the José Martí International Airport.

Godínez, like other security agents posing as dissidents, paid a high personal price for her work. Both her mother and father were revolutionaries and she had to leave home and move to Havana in 1995 because of her counter-revolutionary activities. “This whole process has been hard for my family,” she said in 2003. As Godínez told it, her 80-year-old father learned the truth when he saw her interview on Mesa Redonda, and said to her siblings, “I have seen an angel turn into a devil, but a devil turn into an angel, never.”

“And he started to cry.”

Today Godínez is a journalist, and she is working on a book about her experiences as an double agent. End

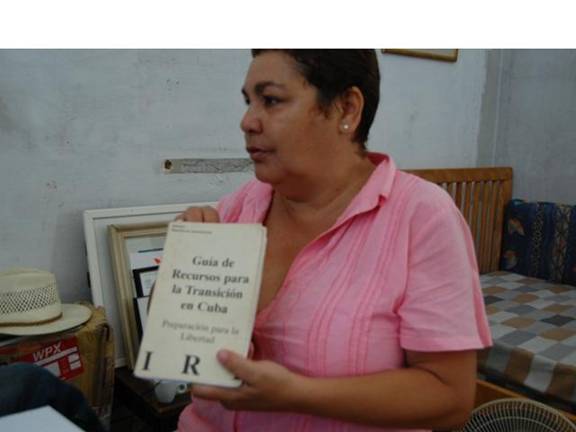

Explanation of photograph, taken July 24, 2008

(Taken from Los Disidentes, p. 29)

I have a booklet, the name of which is Resource Guide for the Transition. It’s a manual, in two parts. First, they explain what a transition is and what to do in the social sphere, the military sphere. The second part is a list of organizations that support the “countries in pre-transition” and of the organizations that support the “countries in post-transition.” You can see there the phone numbers, fax numbers, the names of individuals to contact. That is, everything. Robin Meyer put it in my hands as something very important and ultra-secret, which I was to memorize and disappear. (Los Disidentes, p. 29)

DSC_1968.JPG

DSC_1975.JPG

Aleida Godínez trabajó para los servicios de inteligencia cubanos como doble agente desde 1991 hasta 2003…

11:43h. del

Sábado, 2 de agosto.

LA REPUBLICA:

http://www.larepublica.es/spip.php?article11967

|

Diana Barahona Aleida Godínez trabajó para los servicios de inteligencia cubanos como doble agente desde 1991 hasta 2003, cuando se volvió una testigo clave en los juicios de 75 individuos detenidos por trabajar para los Estados Unidos como disidentes. Una reconocida disidente ella misma, Godínez pasó años insinuándose en el mundo de la oposición a sueldo, probando a ser una empleada capaz y leal de la Sección de Intereses y de la CIA en la Habana. Desde sus comienzos humildes como activista de derechos humanos en su pueblo natal de Ciego de Ávila, Godínez más tarde se hizo periodista independiente, bibliotecaria independiente, fundadora del Partido Cubano Demócrata Crisitana, dirigente de dos organizaciones laborales independientes, la mano derecha de Marta Beatriz Roque, una espía de confianza de una agente de la CIA y colaboradora cercana de Frank Calzón, director ejecutivo del Centro Por una Cuba Libre. Todos los títulos eran ficticios, y todas las organizaciones seguían las órdenes de la SINA. En su carácter de disidente célebre Godínez fue "corresponsal" de Radio Martí, entregando 102 reportajes sobre supuestas violaciones a los derechos humanos entre 1992 y 1993. Ella se reunía con diplomáticos y delegaciones de varios países, y recibía cantidades de dinero, regalos y comidas gratuitas. Se le dio la tarea de espiar para los EEUU, y llevaba la información requerida, recopilada por sus jefes cubanos, a sus jefes americanos en la SINA. Através de los años, sólo había dos cosas que movían a los disidentes: el dinero y visas para los Estados Unidos. El negocio de las visas, sin embargo, era cuchillo de dos filos; aunque la posibilidad de conseguir una visa atraía gente al movimiento, pronto salían para Miami. La nómina de disidentes era como la fuerza laboral de un McDonald’s, lo que significaba que la SINA constantemente tenía que capacitar nuevos empleados. Por su parte, Godínez avalaba a muchos que querían visas. En su entrevista con Rosa Elizalde y Luis Baez para Los Disidentes (Editora Política, 2003) ella dio una idea del cambio de personal: Tenía 11 personas en la delegación del Movimiento Cubano Demócrata Cristiano. De ellas, ocho estaban tratando de irse del país y, de hecho, están fuera de cuba en estos momentos. De los otros tres, luego supe que uno era agente nuestro. Lo mismo ocurría con los otros movimientos. El que tenía un membresía un poquitico mayor era el Comité Cubano Pro Derechos Humanos, con unos 15 ó 20. Todos se fueron del país en aquellos años (p. 10). Godínez es una mujer alegre, sociable con una voz que manda. No es difícil imaginarla en su papel de contrarevolucionaria, que no es un trabajo para tímidos. Ella se jactó de ser la persona que hizo que el gobierno de Clinton empezara a mandar grandes sumas de dinero a los disidentes en 1995. Tal como ella cuenta la historia, se encontraba en una reunión con la disidencia cubana y Ann Patterson, sub-secretaria para asuntos del Caríbe. Cuando Patterson pregunto, "¿Qué hace falta para derrocar la revolución de Castro?" ninguno de los presentes contestó. Así que Godínez tomó la batuta y dijo, "Bueno, cuando Napoleón estaba haciendo la guerra, alguin le preguntó qué hacía falta para ganarla. Él respondió que necesitaba sólo tres cosas: dinero, dinero y más dinéro, y eso es también lo que necesitamos nosotros: dinero, porque si no hay dinero ni hay recursos no se puede hacer nada." Pero la verdad es que las sumas sólo eran grandes para la economía cubana; la mayor parte de los millones destinados para Cuba se queda en Washington y Miami, tal como confiesa un informe publicado en 2008 por la Fundación Nacional Cubano Americana. Godínez hizo su primer contacto con la SINA el 20 de junio de 1994. "Cuando se crea un partido político que yo fundé con cuatro personas más, yo presento el partido político a la Sección de Intereses," dijo. En el sede de la SINA ella conoció a Christopher Sibila, de quien Godínez afirma que no se ocultaba para reconocer que era "el oficial CIA". Sibila la presenta con su jefe, Charles O. Blaha, quien le facilitó un pase "abierto" al sede. Allí, ella tenía acceso a teléfonos, ordenadores y fax. Pero fue la llegada dos meses después de Robin Diane Meyer que fue de más importancia para su trabajo de doble agente. "Ella llega en agosto. Ya Charles O. Blaha le recomienda que se entreviste conmigo. Y a partir de esa recomendación – que son recomendaciones muy especiales porque se supone que esta gente te han estudiado, te han caracterizado, te conozcan – cuando Robin Diane Meyer llega en Cuba me considera practicamente una de ellos". A Meyer se le había encargado la tarea de unificar a la oposición, y llegó a autotitularse ’la madrina de la oposición". Ella llevaba consigo un manual que se llamaba, Guía de Recursos para la Transición en Cuba. Esta guía fue publicada por el Comité para la Transición en Cuba del Instituto Republicano Internacional, que dirigía en aquellos tiempos (1996) Jeb Bush. Otros miembros notables eran Frank Calzón, Pepe Cárdenas (de la FNCA), Ricardo Ofil, Ernesto Betancourt, Elliot Abrams, Lincoln Díaz-Balart, Jaime Fernández, Daniel Fisk, Adolfo Franco (hasta el último escándalo, director de USAID) y Carlos Franco. "Pero una de las personas que más me llama la atención de las personas que forman el comité fue Porter Goss, que después, pasados los años, fue el jefe de la CIA en Estados Unidos". También en el comité estaban Jeanne Kirkpatrick, el Senador Connie Mack, Otto Reich, Roger Noriega – "bueno, toda una serie de individuos que tienen un pasado muy vinculado a los servicios secretos del gobierno de los Estados Unidos". En 1995, como parte de un reciente acuerdo migratorio, a Meyer se le permitía viajar por todo el país, y ella visitó a Godínez varias veces en Ciego de Ávila. "A partir de allí ella me empezó a dar un tratamiento especial. Dentro de ese tratamiento especial que ella me da, ella me sugiere que le escriba a Frank Calzón. Ella me dice que hay un grupo de organizaciones no-gubernamentales, fundaciones, que están en la mejor disposición de ayudar a la disidencia en Cuba. Y para eso pone en mis manos un libro que se llama Guía de Recursos para la Transición en Cuba". Godínez dice que el libro era como su biblia, porque le orientaba "para redactar cartas y para no salirme de la letra" en los encuentros con visitantes norteamericanos y representantes diplomáticos. Godínez se reunió con Meyer más de 100 veces en los dos años antes de que ésta fuera expulsada de Cuba en 1996. "Esta señora, oficial de la CIA, muy amiga mía, fue la que me puso en contacto con Frank Calzón". El primer director ejecutivo de la FNCA, Calzón pasó a ser directiva de Freedom House, una organización financiada por el gobierno para "promover la democracia" con una lista de directivas conformada por importantes neoconservadores como Donald Rumsfeld, ex-directores de la CIA, dirigentes laborales con fuertes vínculos a las mafias y periodistas P.J. O’Rourke y Mara Liason. Durante la década de los 1990 Calzón tenía la costumbre de mandar enviados a Cuba a nombre de Freedom House, para repartir dinero y realizar espionage. Uno de sus agentes, David Norman Dorn, fue detenido en agosto de 1997 y "confesó la realización de espionage en Cuba, tomando fotos a objetivos económicos" según Los Disidentes (p. 24). Esto dio una publicidad indeseada para Freedom House, así que en octubre del mismo año Calzón llevó su personal de Freedom House y, con ayuda de Otto Reich, formó el Centro por una Cuba Libre, con $200 000 de fondos privados de cubanoamericanos, $400 000 de USAID y $15 000 de la NED. El Centro también podría llamarse la vaca lechera de Frank Calzón en vista de las subvenciones millonarias que percibe y las magras cantidades que realmente llegan a la isla, y el hecho de que a su socio Felipe Sixto, se descubrió en abril de este año que había desfalcado $500 000 en el transcurso de tres años. Godínez dijo que en 1996 Meyer le propuso hacer una carta a Frank Calzón en Freedom House, solicitándole cuáles eran sus necesidades, "y yo, muy prudentemente como ando por orientaciones de la Seguridad del Estado, hago la carta, y le solicito medicamentos, literatura sobre el tema de los derechos humanos, y entonces yo le entrego la carta a ella, y me dice, ´Vamos a pasarla aquí en la Sección de Intereses através del fax de la Sección de Intereses´. "Ella ya me había entregado el número – el libro que estoy hablando. Frank Calzón entonces era el director del programa Cuba Libre de Freedom House. Había recibido recientemente $500 000 de las manos del Presidente Clinton para lograr la transición de Cuba. Dicho en español, para la derrota de la revolución". "Yo llevé ese documento a la Sección de Intereses y lo curioso del caso fue que no lo enviaron, sino que unas semanas después, Frank Calzón me llama por teléfono a mi casa. El teléfono mío no aparecía en el directorio de La Habana. O sea, que evidentemente hubo una vinculación entre Robin Meyer y Frank Calzón". La primera conversación que tuvo Godínez con Calzón marcó el comienzo de una larga relación. Cuando se le preguntó qué tan buena era esa relación, Godínez dijo, "muy buena. Tan buena que yo lo llamaba a su casa cada domingo a las 2:00 de la tarde, todos los domingos." "Frank Calzón me enviaba dinero dos veces al año – mucho dinero". Godínez recibió su último pago en marzo de 2003, justo antes de que fueran detenidos los disidentes. En esos momentos, el grupo de Roque mantenía una "ayuna" para la liberación de un integrante encarcelado, durante la cual comían potages y regalaban avales para visas. Godínez llegó a la ayuna, recogió su dinero, y salió a comer. Los "ayunantes" fueron detenidos más tarde ese día. "Y yo me quedé con el dinero de Frank, por supuesto". Godínez es la misma agente que en 1999 conoció al bibliotecario neoyorquino Robert Kent, que se presentó con ella como Robert Emmet. Afirma que Calzón no podía viajar a Cuba, así que mandó a Kent en su representación. Kent ya había viajado previamente a Cuba de parte de Calzón y Freedom House, pero para su viaje de 1999 no se sabe qué organización lo patrocinaba, ya que Freedom House ahora sostiene que no lo conocen. Kent llegó a Cuba el 22 de febrero de 1999, e hizo contacto con Godínez dos días después, el 24 de febrero. Por razones de seguridad, ella tenía una casa distinta en La Habana para las reuniones. Cuando Kent llegó a esa casa, dijo ella, traía un "gusano muy grande" (una lona). Adentro había medicinas, cosas de aseo, baterías, radios, relojes, cameras y un radio de honda corta 10 bandas marca Radio Shack para que los dos se comunicaran. Godínez dice que él le dio un reloj Casio con GPS, el radio honda corta y una camera 35 mm de marca corriente. Kent compró para ella película Kodak. Lo que Calzón quería era información sensible, dijo Godínez. Kent le preguntó sobre yacimientos de petróleo y sobre una empresa estatal que cobraba a los turistas por servicios médicos. "La empresa se llamaba Servimed", dijo. "Querían saber precisamente quién era el director y qué clases de servicios se ofrecían". Kent también le encargó a Godínez la tarea de tomar fotos de la seguridad de la casa de Carlos Lage Dávila, entonces presidente del Consejo de Ministros. "Él me explicó que el gobierno norteamericano pensaba que Carlos Lage podía ser el sustituto de Fidel Castro", dijo. "Yo tenía que tomar fotos a petición de Frank Calzón. Era quien había mandado a Robert Kent a Cuba, él había financiado el viaje." "Aparte de eso, nos había traído $500 para que Robert Kent me los entregara a mí. Pero Kent se sintió a gusto conmigo y en vez de darme los $500, me dio $700 para que me comprara una moto". Cuando se le preguntó si esto podía ser una iniciativa personal de parte de Calzón, Godínez dijo que lo dudaba, ya que su contacto inicial con Calzón había sido por Robin Meyer. "Curiosamente, Robert Kent pide la misma información sensible que me pedía Meyer: yacimientos de petróleo y Servimed". Ante la pregunta de si Kent, el fundador de Amigos de Bibliotecas Cubanas, visitó alguna vez una biblioteca, Godínez dijo que no. "El proyecto de las bibliotecas cubanas empezó en octubre de 1998, y cuatro meses después, Kent llegó Cuba; peró él no trajo libros", dijo. "Sólo había una biblioteca independiente en Las Tunas, y Kent no fue a Las Tunas". En este momento Godínez sacó una foto de la biblioteca independiente que todavía conserva en su casa como recordatorio de sus años como agente de seguridad. Se ve un anaquel pequeño lleno de libros y papeles. Ella dice que llevaba a Kent a las casas de varios disidentes, dondé él pedía permiso para usar el baño y regresaba con dinero para ellos. Godínez tomó la fotos que se le había dicho que tomara de la casa de Lage, las cuales fueron decomisadas de Kent en el Aeropuerto Internacional José Martí. Como otros agentes de seguridad que se pasan por disidentes, Godínez pagó un precio personal alto por su trabajo. Sus padres eran revolucionarios, y ella tuvo que salir de Ciego de Ávila y mudarse a La Habana en 1995 por sus actividades. "Todo este proceso ha sido duro para mi familia" dijo en 2003. "Y les cuento algo para que tengan una idea de cómo ha sido todo: Mi papá tiene 80 años, vive aún en Ciego de Ávila. Él estaba con mis hermanos el día que pasaron la entrevista por la Mesa Redonda – ahí se enteró – y dijo: ´Yo he visto un ángel convertirse en diablo, pero un diablo convertirse en ángel, no.´Y se echó a llorar". Hoy Aleida Godínez es periodista, y está escribiendo un libro sobre sus experiencias como doble agente. |