La Jiribilla No. 309, April 7-13, 2007

MARX BEYOND SOHO

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmnn

original:

http://www.lajiribilla.co.cu/2007/n309_04/309_09.html

In a well-recognized phrase, Martí says

that there is no real death when one has led a meaningful life. This could

be the ideal preface to any article written today about Karl Marx. One

hundred & twenty-four years following his death, the spectre he invoked and

described is not only haunting Europe, but the entire world. Coinciding with

the commemoration of this anniversary of Cuban television, a version of a

play that three years ago successfully appeared in the Havana theater is

being broadcast: Marx in Soho by Howard Zinn, activist, essayist and

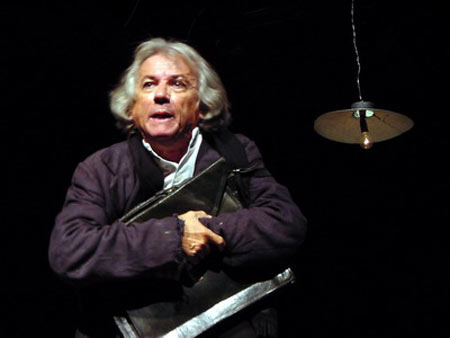

playwright. Michaelis Cué, actor/director, starred in this one-man

production in the theater as well as on TV. Michaelis’s well-known artistic

development drew from his participation in such important groups as Studio

Theater, the Bertolt Brecht Political Theater and My Theater, among others,

as well as his work as a director, were possibly why when it was decided to

present this play in Cuba his name immediately came up. Zinn’s play has

enjoyed great theatrical success not only in Cuba but in many Latin American

countries, obtaining favorable reviews in the media wherever it has been

presented. Venezuela, Chile, Costa Rica, Perú, México have all witnessed

this exceptional work which our country plans to take on a nationwide tour

winding up at the Adolfo Llauradó Salon for its 100th

presentation. It’s quite interesting to see how such diverse audiences

discover different meanings – all of which, in my opinion, are valid – in

the dramatic text. The interest it has awakened is vindication of the

thinking of one of humanity’s great ideologists and indicates that Marx

still has much to say, and not only in Soho.

Many

have characterized Marx in Soho as an heir of political theater and

speak of the influence of Brecht’s Galileo Galilei presented by

Vicente Revulta.

What influences do you see here?

Many

have characterized Marx in Soho as an heir of political theater and

speak of the influence of Brecht’s Galileo Galilei presented by

Vicente Revulta.

What influences do you see here?

I was Vicente’s right hand for 12 or 13

years, so it is logical that his influence is seen in my acting and

directing. I recognize I owe a great deal to him, and although I have had

various teachers, I learned a great deal about acting and directing from

him. As to the reference that this is political theater, I feel that

everything in theater is political. Naturally, as this work is about Karl

Marx, everyone talks about political theatre. But today if someone were to

present another political work, Fuenteovejuna by Lope de Vega, it’s

more evident when the play is about this person (Karl Marx). The principals

of my portrayals in the theater are influenced by both Brecht and Grotowsky,

but it is Grotowsky’s principals that I use in my voice and body language.

I’m unaware of it when I’m on stage.

Omar Valino said that your role as Marx showed maturity as an actor.

But you directed as well. What was that like and which was more difficult?

The play was given to me by Julio César

Ramírez whom I was going to direct. But as I read it I became so excited I

said: I have to do this, and I began studying it from the actor’s point of

view. Logically as I was to direct it I had a general overview of the work.

I tried not to let that influence me, but to devote myself to looking at it

from the point of view of the actor. Julio had told me to let him decide

what parts he would use and I was interfering without even being aware of

it, preventing him from turning the work into a political lecture, because

the work is quite long and there are parts that the Cuban audience would be

bored with. So I stuck with the part of the monologue where the actor is

much more human, doing it all from the actor’s point of view. Bárbara Rivero

started working with me as an advisor. Later she gave me a version that she

had written and I began to study it. The first run-throughs were with only

Julio and myself. Later Julio got very busy because he was also working in

a TV soap opera, and I was working very slowly because there was no date set

for it to open. Suddenly Bárbara Rivero told me that Howard Zinn was coming

to the opening scheduled to be in 15 days! That’s impossible, I said,

because it’s not ready. The only thing I can do is learn the text in 15 days

and put it on as a rehearsal for him after which I can set a date for the

opening and he can attend. And so I closeted myself in the theater and ended

up directing myself as I put it together. Finally Howard Zinn arrived, we

met and talked a lot about the play and the next day he came to the

rehearsal. Even though everything was hastily put together, the script, the

movements, he liked what he saw. Despite that, I told him that it was not

what would be presented at the opening and I requested a month and a half

more (before the opening). He was here for the first few days of April, and

we agreed that the opening would be on May 26. He arrived three days before

and was awarded Honoris Causa

and his book, A People's History of the United States was published.

The opened on the 26th, but was a

completely different version from what he had seen at the rehearsal, which

had only been a rough version, because after that I put it all together. I

dedicated myself to putting it on stage. I was in a kind of trance. I

didn’t sleep, didn’t eat. I got up at dawn because I knew that the work was

in a vacuum. My career was at stake. From the outset I knew I couldn’t

imitate Karl Marx. I wouldn’t wear a beard or makeup, because Marx is an

icon, but he was also a human being and instead of imitating Marx I decide

to find what there was of Marx in me, what I had of Marx, what his ideas had

to do with me. With that as a beginning, I tried to present the man through

his thinking, his ideology, his relationship with his family and through his

humanism. It was impudent of me because everyone was waiting for a man with

a beard, long hair, and I presented him through me because any other way

would have been to continue respecting an icon, and I tried to de-sanctify

the image that everyone has of him. I really enjoyed that role more than

any other even though every presentation is different, every play follows

its own path, and luckily I felt it deeply from the beginning and that

helped me mount the work in record time. I didn’t want complicated scenery;

a simple stage setting but more complex acting. I would throw myself into

the role and seek the truth, and it turned out fine.

I learned something about Howard Zinn’s visit and he has said that

yours is the best stage presentation of his work that he has seen. Would you

speak a little about the relationship between you two following the

presentation?

He was very nice and was interested in

what parts of the play would be cut. He confessed to me that he thought that

the monologue in Cuba couldn’t be included because there are parts that are

very sensitive and he was surprised when he saw that the cuts were precisely

those which would have meant preaching to the choir. He expected that I

would have cut the other parts and would have left the preachy part but I

left the most sensitive parts because I had a lot of freedom (in mounting

the play) and so I decided not to cut it, and he found that fascinating. We

communicated with each other easily even though he doesn’t fully understand

Spanish. He’s very pleasant and open. In the US many versions of Marx

in Soho have been seen. Nearly all universities have presented it.

Moreover, it’s been on Broadway and has been seen internationally, but it’s

never been put on in Spanish and he was very interested in how it had been

done in Cuba. He thought that the work would be "very Cuban", but when he

saw that I was adapting it for Latin America he in greed and was very

pleased. He sent me an e-mail saying that I had made his play famous in

Latin America. He praised the production highly and used it to describe

this country’s artistic level, as Cuban theater is very active, in the

vanguard as it were. I believe he was more interested in it from the

political perspective without much artistic expectation, but I always felt

that if it wasn’t well done there was no sense in putting it on. If it has

any political, ideological, practical value, it is because it was well

adapted. If it had flopped, no one would have talked about it.

The

adaptation was recently televised. What was it like adapting Marx in Soho

to the small screen without losing the intensity that is so different in two

such different mediums?

The

adaptation was recently televised. What was it like adapting Marx in Soho

to the small screen without losing the intensity that is so different in two

such different mediums?

I had to throw myself once again into the

play. Jorge Alonso Padilla, the director, and Raúl García, the co-director,

saw it on stage and the next day they called me filled with enthusiasm

telling me they wanted to adapt it for TV. I asked about the script and

they gave it to me. When I saw it I loved it as it was very ingenious and

solved many of the problems involved in bringing it to TV. I tell you that

once more I had to use my imagination because the theater is for a more

limited audience and TV is for millions. Padilla, Raúl and I understood

that, and used my theater presentation as a guide, but a TV broadcast is

different. My first challenge was to shed the excessive theatricality even

though I feel that the spectator should understand that it’s a theater piece

adapted for TV and I couldn’t just make it “natural” with understated acting

or tone it down. The three of us were aware of the importance of the extras

to give it atmosphere. In the end it was very well done because the script

was technically very good from the start. Padilla made a very secure

adaptation and that is a great help to an actor.

Throughout Latin America there is a trend to the left.

During your tour, how was

it received by those Latin American audiences?

For me it was a real surprise. The

communication, the level of acceptance was very impressive. When I was in

Perú the audience reaction was exciting. I was going to do the show at

universities, but I realized that on that tour the University of San Marcos,

the oldest on the continent and with a leftist tradition, had not been

included. Vallejo studied there and I asked to put the play on there. It

was spectacular. That was the first time it had been given before a Latin

American audience.

Later, in Costa Rica, a country with a

great cultural tradition and many prejudices concerning Cuba, I was quite

concerned. The work was part of the Costa Rican Arts Festival program, a

very important international festival. It was included because the

Festival’s director had been in Cuba and seen it here. On the first night

the theater was completely filled and the console broke 10 minutes before

the play was to begin. The technicians there told me it was sabotage

because I was Cuban, and I told them I would go on without music, with just

a light, but the play would go on. Well, it wasn’t sabotage. The console had

really broken, and they brought another one from a nearby theater and

public’s reaction was totally unexpected; I received an impressive ovation.

The play defended Marx’s ideas but humanizing him instead of making him

cold, and they found that very interesting; it moved them. In Cuba the

audience is moved in a different way because everyone here has studied

Marxism. There (in Costa Rica) they have also studied him, but from a

different point of view and so it was viewed differently. In Cuba you show

Karl Marx attacking capitalism and it’s nothing new, but in Costa Rica the

progressives that attended liked it because what they saw and heard was

presented with humor. Later I was in Chile and it was also very well

received. The theaters were full; hundreds of people.

As you yourself have said, in Cuba the work is received differently

than it is abroad and its success is attributed in good part to the fact

that the creator’s philosophy has for the past 45 years served as the basis

of the social process.

Howard Zinn is very familiar with the

biography of Karl Marx, his thinking, and Zinn is a man with a very special

sense of humor. Zinn’s original text is very well balanced, not

paternalistic, written by an absolute detractor of capitalism, but also an

absolute detractor of what was called ‘real socialism’. Howard Zinn is a

profound Marxist. He is a man who isn’t easily taken in by what happened in

‘real socialism’. He is a severe critic of Stalinism and that is seen in

his work. In Cuba this criticism says a lot because the socialism camp

didn’t collapse because of a war, it imploded because of its internal

contradictions and errors. This has been brilliantly analyzed by Fidel and

I have recently seen an article by Armando Hart in Cubarte in which

he tears into the errors committed there. Howard Zinn follows that same

line. The diverse interaction within different audiences says that this is

a polemical work and a piece of theater that says many things.

|

|

Entrevista con el actor Michaelis Cué |

|

|

|

Yinett Polanco•

La Habana

Fotos:

Pepe Murrieta

Una reconocida

frase martiana dice que la muerte no es verdad cuando se ha cumplido bien el

sentido da la vida. Este podría ser el exergo ideal para cualquier artículo

sobre Carlos Marx que se escriba hoy día. Ciento veinticuatro años después de su

muerte el fantasma por él invocado y descrito no solo recorre Europa, sino que

se ha extendido por todo el mundo. Coincidente con la conmemoración de este

aniversario la televisión cubana transmitió por estos días una versión de una

obra de teatro que hace tres años conmovió la escena habanera: Marx en el

Soho, del politólogo, ensayista y dramaturgo norteamericano, Howard Zinn. En

la piel del Moro estaba

―tanto

en la versión televisiva, como en la teatral―

el actor Michaelis Cué, quien también se autodirigió en el unipersonal sobre las

tablas. La reconocida trayectoria artística de Michaelis, desarrollada a partir

de importantes grupos como

Teatro Estudio, Teatro Político Bertolt Brecht y Teatro Mío,

entre otros, y su experiencia adicional como director del medio, fueron

posiblemente las causas de que, cuando en Cuba se decidió montar esta obra, se

pensase inmediatamente en él para interpretar el personaje. Del éxito que ha

tenido esta puesta en escena de la obra de Zinn, no solamente en Cuba, sino en

muchos países de América Latina, dan fe las diversas pero siempre elogiosas

críticas aparecidas en diferentes medios de comunicación de todos los países

donde se ha presentado el espectáculo. Venezuela, Chile, Costa Rica, Perú,

México, han sido testigos de esta obra excepcional que en nuestro país pretende

volver con una gira nacional que culminará en la sala Adolfo Llauradó para

celebrar su función número 100. Resulta interesante como públicos tan diversos

son capaces de encontrarle múltiples sentidos ―y, en mi opinión, todos válidos―

al texto dramático. El interés que despierta esta revindicación del pensamiento

de uno de los grandes ideólogos de la humanidad indica que Marx aún tiene mucho

que decir… y no solamente en el Soho.

|

|

Muchos han

calificado a Marx en el Soho como un heredero del teatro político y

hablan de la influencia en su puesta en escena del montaje de Galileo Galilei,

de Brecht por Vicente Revuelta, ¿hasta qué punto son ciertas estas influencias?

Yo trabajé de

mano derecha de Vicente durante 12 ó 13 años, entonces como es lógico actoral y

estéticamente tengo una enorme influencia suya. Reconozco que le debo cantidad,

pues aunque pasé por varios profesores, viendo actuar y dirigir a Vicente

aprendí mucho. Referente a la valoración de este teatro como “teatro político”…

pienso que todo teatro es político. Claro, como esta obra es sobre Carlos Marx

enseguida hablan de teatro político, pero si uno hoy monta Fuenteovejuna,

de Lope de Vega, eso también es teatro político aunque es más evidente cuando se

escoge para hacer una obra a esta figura. En los postulados de mi puesta en

escena para el teatro sí hay una influencia brechtiana, como la hay grotowskiana,

actoralmente el uso que yo hago del cuerpo y de la voz viene de los postulados

grotowskianos. Es, en definitiva, una mezcla no consciente de cosas.

Omar Valiño

afirmó que su encarnación de Marx era una muestra de su madurez como actor, pero

usted hizo además la versión de la obra y se autodirigió, ¿cómo fueron estos

procesos y cuál le resultó más difícil?

Esta es obra

llegó a mí de manos de Julio César Ramírez, quien iba a ser su director. Para mí

fue especial porque en cuanto la leí caí en un estado febril con la obra y me

dije: yo tengo que hacer esto. Como me la iba a dirigir Julio, empecé

estudiándola desde el punto de vista del actor. Lógicamente, como yo dirijo

tenía una mirada general sobre la obra pero trataba de no dejarme influenciar

por ella, sino dedicarme a verla desde el punto de vista del actor. Julio me

había dicho que le fuera haciendo sus cortes y fui trabajando en su dramaturgia

un poco sin darme cuenta, huyéndole a que la obra cayera en el teque político,

porque la obra es mucho más larga y hay zonas de ella que el público cubano no

hubiera resistido y me circunscribí a la parte del monólogo donde el personaje

es mucho más humano, pero todo eso lo fui haciendo desde el punto de vista del

actor. Bárbara Rivero

comenzó a hacerme la asesoría. Luego me

entregó una versión que ella había hecho, yo comencé a estudiarla,

pero los primeros encuentros fueron entre Julio y yo: después él se complica

porque estaba como actor en una telenovela y yo la iba trabajando muy lentamente

porque no tenía fecha de estreno. De pronto Bárbara Rivero me dice: Howard Zinn

viene al estreno de la obra dentro de quince días y yo le dije: eso es imposible

porque yo no tengo nada en la mano, lo único que podemos hacer es comprometerme

a aprenderme el texto en quince días y montarme la obra para que él vea un

ensayo, a partir del cual yo le pondré fecha para que venga al estreno.

Efectivamente me encerré en el teatro y terminé de dirigírmela mientras montaba.

Al fin llegó Howard Zinn, nos reunimos, hablamos mucho sobre la obra y al otro

día fue a ver el ensayo. Aunque yo tenía todo prendido con alfileres: la letra,

los movimientos… él se fascinó con lo que vio. A pesar de eso yo le aclaré que

eso no era lo que iba a ver el día del estreno y le pedí un mes y medio más de

trabajo. Él estuvo aquí los primeros días de abril y concertamos el estreno para

el 26 de mayo. Vino tres días antes y ahí se le dio el Honoris Causa y se le

publicó el libro La otra historia de los Estados Unidos. El 26 se estrenó

la obra, pero yo hice algo totalmente diferente a lo que él había visto en el

ensayo, que había sido el montaje básico, porque después yo maduré aquello y me

dediqué a la puesta en escena. Yo entré en un estado de trance con el

espectáculo: no dormía, no comía, me levantaba de madrugada, porque sabía que me

había lanzado al vacío con esa obra, me estaba jugando mi carrera. Desde el

principio sabía que

no podía tratar de imitar a Carlos Marx, ni ponerme barba ni afeites, porque

Marx es

un ícono pero también era un ser humano y en lugar de acercar Marx a mí, traté

de ver qué

yo tenía de Marx y cuánto de sus ideas tenían que ver conmigo. A partir de ahí

traté de dar al hombre por su pensamiento, por su ideología, por también por la

relación con su familia y

por

su humanismo. Eso fue atrevido de mi parte, porque todo el mundo esperaba a un

hombre con su barba y su pelo largo y yo partí de mí, porque lo otro hubiera

sido como seguir respetando el ícono y yo traté de desacralizar la imagen que

todo el mundo tiene de él. Realmente disfruté este montaje como ningún otro,

aunque cada montaje uno lo hace distinto, cada obra tiene su camino y por suerte

este camino yo lo encontré bastante al inicio y eso me ayudó a montar este

espectáculo en tiempo récord. Yo no quería una puesta en escena compleja, quería

algo simple desde el punto de vista escénico pero más complejo desde el punto de

vista actoral, entregarme más, buscar la verdad y así salió.

Me adelantó algo

sobre la visita de Howard Zinn y él ha dicho que la suya es la mejor puesta en

escena de su obra que había visto, quisiera que me abundara sobre la relación

entre ustedes a partir de la obra.

Él fue muy

respetuoso conmigo pero estaba muy interesado en saber cuáles eran los cortes

que yo iba a hacer. Me confesó que pensaba que este monólogo en Cuba no se

podría hacer porque hay zonas del monólogo muy delicadas y se quedó asombrado

cuando vio que los cortes hechos a la obra fueron precisamente los cantos al

marxismo, los cuales para Cuba serían teque. Esperaba que yo hubiera quitado

todo lo otro y hubiera dejado el teque y por el contrario yo dejé las zonas más

conflictivas porque trabajé con una libertad enorme, decidí qué cortaba, qué no,

y eso a él le fascinó. La comunicación entre nosotros fue muy fácil a pesar de

que él no domina muy bien el español, es un hombre muy simpático, muy abierto.

En EE.UU. se han hecho muchas versiones de Marx en el Soho, casi todas la

universidades han montado esta obra y además se ha montado en Broadway, esta es

una obra de vida internacional, pero no se había hecho en español y a él le

interesó mucho que se hiciera en Cuba, pero él pensó que la obra iba a tener la

vida cubana y cuando se enteró de que yo estaba haciendo un periplo

latinoamericano estuvo muy al tanto, muy contento, por eso me mandó un email

diciendo que yo había hecho su obra famosa en Latinoamérica. Fue muy elogioso

con la puesta en escena, la cual le sirvió además para descubrir el nivel

artístico de este país, pues el teatro cubano tiene zonas que están muy vivas, a

la vanguardia. Creo que a él le interesaba más el punto de vista político y con

el lado artístico no tenía muchas expectativas, pero yo siempre supe que si esto

no quedaba bien lo demás no tenía sentido. Si algún valor político, ideológico,

práctico, tiene, es porque quedó bien; si hubiera quedado mal nadie hubiera

hablado de ella.

|

|

La obra fue

exhibida recientemente en la televisión, ¿cómo fue el proceso de llevar Marx

en el Soho a la pequeña pantalla sin confundir los lenguajes de estos dos

medios tan diferentes?

Eso fue volverme

a lanzar al vacío. Jorge Alonso Padilla (el director) y Raúl García (quien hizo

la codirección y el trabajo de arte) fueron a ver la obra y al otro día me

llamaron muy entusiasmados diciéndome que querían hacer una versión. Yo les pedí

que hicieran el guión y me lo presentaran. Cuando lo hicieron, el guión me

encantó, pues era muy ingenioso y resolvía muy bien la traslación a la pantalla.

Digo que ahí volví a lanzarme al vacío porque el teatro siempre es de elite pero

la televisión es para millones de personas. Padilla, Raúl y yo nos entendimos

muy bien, partíamos de mi montaje teatral pero efectivamente el lenguaje

televisivo es otro. Mi primer reto era quitarle la teatralidad actoral excesiva

aunque siempre defendí que el espectador debía darse cuenta de que era una obra

de teatro trasladada a la televisión, yo no podía hacer tampoco un naturalismo,

una subactuación o una actuación en tono menor y además los tres estábamos

conscientes de la importancia de los extras para dar la atmósfera de la obra,

pero al final todo quedó muy bien porque había un guión técnico muy inteligente

desde el principio, Padilla trabajó con tremenda seguridad y eso ayuda mucho al

actor.

En muchas partes

de América Latina se está dando un proceso de viraje hacia la izquierda, ¿cómo

era el diálogo entre esos públicos latinoamericanos y la obra en su periplo de

exhibición?

El diálogo en Latinoamérica para mí era sorprendente. La

comunicación, el nivel de aceptación del trabajo era impresionante. Yo estuve en

Perú y en el teatro de las reacciones allí fueron impresionantes. Además yo iba

a dar unas funciones en universidades pero me llamó la atención que en ese

periplo no me hubieran puesto la universidad de San Marcos, la más antigua del

continente y con una tradición de izquierda, allí estudió Vallejo y yo pedí ir

allí y di una función gratis que fue espectacular. Ese fue él primer encuentro

de la obra con el público latinoamericano.

Después en Costa

Rica ―un

país con muchos prejuicios con respecto a Cuba y con una penetración cultural

enorme―

yo estaba muy preocupado. La obra se representó dentro de la programación del

Festival de las Artes en Costa Rica, un festival muy importante

internacionalmente adonde llegó mi espectáculo porque el director del Festival

había venido a Cuba y había visto aquí la obra. La primera noche en que debuté

allá, el teatro estaba repleto y se rompió la consola diez minutos antes de

actuar. Los técnicos de allí me dijeron: esto es sabotaje porque usted es cubano

y yo les respondí: yo salgo a actuar sin música, con un bombillo, pero salgo a

actuar. No era un sabotaje, se había roto la consola de verdad y trajeron otra

de un grupo teatral cercano y lo que ocurrió con ese público fue una cosa

inusitada, recibí una ovación impresionante porque el espectáculo defiende las

ideas de Marx pero lo hace humanizando al hombre que él fue, rompiendo la

estatua y eso interesó mucho, los movió. En Cuba mueve de otra manera porque

aquí todo el mundo ha estudiado marxismo. Allá también se estudia, pero desde

otra óptica y, por lo tanto, allá el espectáculo funciona de otra manera, porque

que tú en Cuba pongas a un Carlos Marx que ataque al capitalismo a un cubano no

le dice nada nuevo, pero en Costa Rica eso gusta, le gustaba al público

progresista que asistía a las funciones, porque el espectáculo está diciendo de

forma jocosa lo que ellos quieren ver y oír y que la mayoría del tiempo no dicen

sus medios de prensa. Luego estuve en Chile y también fue arrollador. Hablo de

varias funciones en teatros de quinientas personas repletos.

Como usted mismo

dice el espectáculo funciona de diferentes maneras en Cuba y en el extranjero,

aquí se le ha atribuido una buena parte del éxito de la obra al hecho de que

dialogue con el creador de la filosofía que ha servido de base al proyecto

social de los últimos 45 años…

Howard Zinn es un hombre que conoce muy bien la biografía de Carlos Marx, su

pensamiento y es un hombre con un sentido del humor muy particular. El texto

original de Howard Zinn es un gran texto, muy equilibrado, nada paternalista,

escrito por un detractor absoluto del capitalismo pero también por un detractor

absoluto de lo que se llamó el socialismo real. Howard Zinn si bien es un

marxista profundo, es un hombre que no comulgaba con lo que pasaba en el

socialismo real, un crítico atroz del estalinismo y eso lo lleva a su obra. En

Cuba esta crítica del socialismo real nos dice mucho porque el campo socialista

no cayó por una guerra, cayó dinamitado por sus contradicciones y sus errores

internos. Esto ha sido analizado brillantemente por Fidel y en esto días he

visto un artículo de Armando Hart en Cubarte donde desmonta los errores allí

cometidos, y Howard Zinn se mueve en esa línea. La interacción diversa con

diferentes públicos habla de que este es un texto polisémico y un espectáculo

teatral que dice muchas cosas.

Many

have characterized Marx in Soho as an heir of political theater and

speak of the influence of Brecht’s Galileo Galilei presented by

Vicente Revulta.

What influences do you see here?

Many

have characterized Marx in Soho as an heir of political theater and

speak of the influence of Brecht’s Galileo Galilei presented by

Vicente Revulta.

What influences do you see here? The

adaptation was recently televised. What was it like adapting Marx in Soho

to the small screen without losing the intensity that is so different in two

such different mediums?

The

adaptation was recently televised. What was it like adapting Marx in Soho

to the small screen without losing the intensity that is so different in two

such different mediums?