LA JORNADA

February 26, 2007

Translated by Joseph Mutti. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2007/02/26/index.php?section=cultura&article=a10e1cul

Interview with Abel Prieto, Cuban Minister of Culture

Cuba's cultural policies are neither dogmatic nor sectarian.

The Revolution has not promoted "pamphlet" or propaganda art.

Cuba completely supports the notion that total emancipation is related to the democratization of culture, at the same time recognizing the importance and need for the exercise of criticism.

By Arturo Gracía Hernàndez

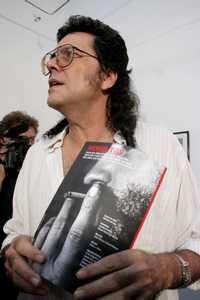

PHOTO:

Socialist realism is an aberration, and when it became official

policy it developed into one of the greatest errors of the

Soviet Union and other nations in the Soviet block, says Abel

Prieto. Photo: Archive, taken in 2006 by Carlos Tischler

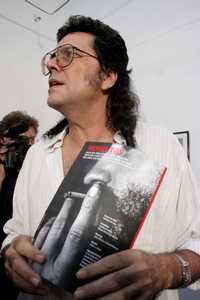

PHOTO:

Socialist realism is an aberration, and when it became official

policy it developed into one of the greatest errors of the

Soviet Union and other nations in the Soviet block, says Abel

Prieto. Photo: Archive, taken in 2006 by Carlos Tischler

PHOTO:

Raúl Castro, interim Cuban President, and Abel Prieto, Minister

of Culture, during the inauguration of the 16th International

Havana Book Fair on February 8, 2007. Photo: Reuters

PHOTO:

Raúl Castro, interim Cuban President, and Abel Prieto, Minister

of Culture, during the inauguration of the 16th International

Havana Book Fair on February 8, 2007. Photo: Reuters

PHOTO:

Elena Poniatowska and Jesusa Rodriguez accompanied by Felipe

Pérez Roque and Abel Prieto, Ministers of Foreign Affairs and

Culture respectively, during the recent International Havana

Book Fair, February 8-18. Photo: Felipe Haro Poniatowski

PHOTO:

Elena Poniatowska and Jesusa Rodriguez accompanied by Felipe

Pérez Roque and Abel Prieto, Ministers of Foreign Affairs and

Culture respectively, during the recent International Havana

Book Fair, February 8-18. Photo: Felipe Haro Poniatowski

--------------------

For the Cuban government, the broadcast of television programs

on three former officials linked to the period of criticism and

repression on the island during what were known as the Gray Five

years between 1971-1976 was an error, commented Cuban Minister

of Culture, Abel Prieto. He added that this has nothing to do

with any change of policy because of Fidel Castro's illness and

the interim presidency of his brother Raúl.

In an interview with La Jornada, the Cuban minister said that this was the official position on the issue that in recent weeks has drawn intense debate in cultural and political circles inside and out of Cuba.

According to Prieto, the former officials who appeared in the programs did not correctly "apply the cultural policies of this country" while in office, and it was therefore a mistake for Cuban television to air the programs "thereby creating the perception among our principal artists and writers" that this was indeed the case.

The interview was carried out in the offices of the Ministry of Culture on February 15 after the Minister found room in his very full schedule of activities related to the International Havana Book Fair - one of the main cultural events of the city.

The "Gray Five" Period

The debate on the Gray Five period began in January, shortly after Luis Pavón Tamayo, Armando Quesada and Jorge Serguera appeared in three television programs, making it appear as if they had made valuable contributions to Cuban culture. Many writers and artists on the island responded critically before what seemed to them a vindication of the three "executioners".

The debate began on the Internet via e-mail, blogs and different forums, and ended in a big meeting in the Casa de la Americas, the emblematic institution of official Cuban culture (La Jornada, February 6).

Luis Pavón Tamayo directed the Council on National Culture (today the Ministry of Culture); Jorge Serguera presided over the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television (ICRT) and was linked to the ''revolutionary trials" against those opposing the state; and Armando Quesada took charge of the area of the theater. In differing ways, the three were leading figures in episodes of censorship and repression during the Gray Five years.

After an outcry by intellectuals on the island, a series of discussions by the Cuban Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC) took place. ''The (Communist) Party leadership sent them a message", says Abel Prieto, "of which I was the bearer of one, to explain that there had been an error in presenting these three former officials on television. Why? Because today the leadership of this country regards that period – which was fortunately brief – with great disapproval, where we set aside the cultural policies that the Revolution implemented in 1961 in which we brought together the cultural work of artists and writers of all tendencies, of all generations - Catholic, Communist, even non-revolutionaries who were sincere".

As an example of the ''correction" of the errors of this five-year period, the Minister of Culture indicated that many of the writers and artists who participated in the present debate had suffered from censorship and repression, but are today recognized by the Revolution: ''they publish their books, they premiere their works".

He particularly mentioned the poet, essayist and narrator Cesar López, to whom this year's International Havana Book Fair was dedicated. At the beginning of the Fair, López read a criticism of the homophobia and repressive acts that were directed against various writers toward the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. (La Jornada, February 10).

Party Endorsement

In Prieto's opinion ''it was very important" that UNEAC included the Party endorsement: ''A series of debates – which was not conjured up for the press - was organized at the Casa de las Americas and was attended by invited Cuban intellectuals for a debate on these errors as to in what they consisted and what harm they had caused. I think that after the discussions and the analysis we have a stronger unity in relation to our present cultural policies".

The situation, observed the Minister of Culture, had caused a ''very aggressive reaction from Miami" and a digital magazine, "Encounter", which is financed by the right-wing National Endowment for Democracy (NED), ''intended to associate what was a mistake, with Fidel's health and with Raúl's performance as interim president of Cuba - as if this had something to do with the function of our institutionalized culture".

On an informal note, long-haired Abel Prieto is one of the most singular senior officials of the Cuban government. His self-assured and courteous manner breaks with the distant solemnity of conventional politicians. A writer and professor of literature, before occupying the Ministry of Culture he was the director of the state magazine "Letras Cubanas" (Cuban Literature) and president of UNEAC.

He is not considered to be dogmatic, and his role has been decisive in the good relations that at present exist between the island's artistic and intellectual community and the Cuban government – especially after periods such as the Gray Five. It is known that during the recent debate, his intervention facilitated an understanding between the different positions taken by one side or another.

During the interview, Abel Prieto also reflected on the different moments of Cuban culture after the triumph of the Revolution. He maintained that ''socialist realism" is ''an aberration", recognizing that there had been ''taboo issues", but defending the importance and the need for criticism.

La Jornada: What are the principles that today govern Cuban cultural policies?

Abel Prieto: First, policies of extraordinary amplitude in terms of artistic expression that have nothing to do with sectarianism, nothing to do with dogma.

LJ: Could we call it a vindication?

AB: We would be able to use that word if you associate it with the sectarian issue, but I believe that it is more than that. It has to do with policies that were implemented in 1961 that defined our national culture as a universal vocation rather than taking a nationalistic approach. After they made those bitter statements about us, Noam Chomsky as well as José Saramago himself visited us. They came here and greeted Fidel.

Cuba completely supports the notion that total emancipation is related to the democratization of culture, of the arts, of film. We're interested in participatory methods with the reader, the spectator, the culturally cognizant - and at the same time we are prepared to learn about and understand the best and most sophisticated art forms.

People here respond en masse to the (annual) Latin American Film Festival, showings of European movies or experimental U.S. movies, in spite of the fact that we are influenced by the worst Hollywood movies. The ballet festival, an art elsewhere associated with the (elite) minority, is also tremendously popular here.

We try to conserve our national memory such as all our works, so as to protect our national heritage. The issue of our youth is fundamental for us, to protect their cultural work so that they don't feel obliged to make concessions in search of a market. Now we have a boom of young film and video producers, of documentary makers. How do we support our projects with so few resources?"

Well, the book industry is an area that has already risen above the crisis thanks to the endorsement of the government, but the film industry is still in a very serious predicament. In music we have created a new recording label called Colibrí (Hummingbird), for troubadours, rappers, rock singers - seeking areas that are not traditionally associated with the market.

Dignity and Resistance

LJ: Is the Revolution sufficiently advanced and strong enough to react in a different way to criticism, even when under siege?

AP: Criticism and reflection on our mistakes has been an ongoing approach of this country. Cintio Vitier said something that I like a lot: ''Our challenge is to build a parliament from the trenches". I believe that the need for debate within the institutions of the Revolution is very obvious. Remember Tomás Gutiérrez Alea's movies "La muerte de un burócrata" (Death of a Bureaucrat) to "Memorias del subdesarrollo" (Memories of Underdevelopment). They were not complacent movies. There are revolutionary and non-conformist films that go from "Memorias del subdesarrollo" to "Fresa y chocolate" (Strawberry and Chocolate), where heresy is, I would say, taken to exceptional levels. Or "Suite Havana", Fernando Pérez's masterpiece that is a song to dignity and resistance. How dignity may be maintained in the worst conditions, in conditions of material ruin.

Look at our literature, from Senel Paz to Leonardo Padura: the Revolution has not promoted "pamphlet art" or propaganda – art has always been critical. There are things that at times are not spoken of when our community elected bodies (peoples powers) and our national assembly are discussed - such as the fact, for example, that a minister is systematically submitted to argument. I believe that the Revolution is mature and has been so at other moments so that its capacity for self-criticism and the ability to reflect upon itself is exercised in a scrupulous way, without fear of what may be said about us outside Cuba.

It is true that in a way a permanent siege has existed in Cuba, but in our culture this siege mentality has never taken a grip: not even when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989. At that time Armando Hart was Minister of Culture and I was president of UNEAC. I remember that in the worst moments, including those many moments of uncertainty, he collectively discussed and analyzed our cultural policies. For us it is fundamental that the artist and intellectual star in the life of the institution.

Taboos

LJ: And there are no taboo issues, or there never were any?

AP: Yes, there have been taboo issues. The subject of homophobia has been recently debated because those people who appeared on television excluded homosexuals. We come from a very strong sexist tradition. When in university in 1968, I knew very upright people who were extremely prepared intellectually, but who were homophobic. That has changed. When the Cuban National Ballet was born, before Alicia Alonso took over, the male dancers had to be chosen from orphanages as Cuban families did not want their children to study ballet because it was seen as a homosexual thing. Today young boys are eager to enter ballet school and their parents eagerly take them.

I cannot say that the problem is resolved – as with racial prejudice. You can sweep institutions of racism and homophobia, but these prevail in some sectors.

LJ: What does the term socialist realism represent for the Cuban government today?

AP: It is an aberration and to become an official policy was one of the greatest mistakes committed in the Soviet Union and in the other Soviet block countries. In "El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba" (Socialism and Humankind in Cuba) Che Guevara is implacable on this, because it associates antiquated realism with socialist ideas. What insanity! And Fidel, in "Palabras a los intelectuales" (Words to Intellectuals), separated himself radically and categorically from the concept. There were people who wanted to impose what is now seen as a sad history of fundamental errors that were committed in those countries in the realm of culture, and that damaged the legitimacy of the process.

LJ: How do you today read the statement (by Fidel in 1961) "Within the Revolution, everything, against the revolution, nothing?"

AP: That is a moment, a phrase, inside the speech "Palabras a los intelectuales". What happens is that when you take it out (of context) it becomes a slogan, and people say OK, but who interprets what is or is not within the Revolution. Fidel himself says that even within the Revolution there has to be a space to work within culture for those intellectuals who are not themselves revolutionary. That is to say, the within is not an exclusion, but a very broad collection of all tendencies. Later there were those who sought to twist the speech for dogmatic reasons.

http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2007/02/26/index.php?section=cultura&article=a10e1cul

La política cultural de Cuba,

sin dogmas ni sectarismos

La Revolución no ha fomentado el arte panfletario, asegura

En la isla se reivindica de manera permanente un pensamiento de la emancipación que se relaciona con la democratización del producto cultural, con la importancia y la necesidad de ejercer la crítica

El realismo socialista es una aberración y convertirlo en política oficial fue uno de los grandes errores en la Unión Soviética y en los demás países del bloque soviético, dice Abel Prieto. Imagen de archivo, tomada en 2006 Foto: Carlos Tischler

Raúl Castro, presidente interino de Cuba, y Abel Prieto, ministro de Cultura, durante la jornada inaugural, el pasado 8 de febrero, de la versión 16 de la Feria Internacional del Libro de La Habana Foto: Reuters

Elena Poniatowska y Jesusa Rodríguez acompañadas por los ministros cubanos Felipe Pérez Roque y Abel Prieto, de Relaciones Exteriores y de Cultura, respectivamente, en La Habana, durante el reciente encuentro editorial efectuado en la capital de la isla, del 8 al 18 de febrero Foto: Felipe Haro Poniatowski

La Habana. Para el gobierno de Cuba, la aparición en programas televisivos de tres ex funcionarios vinculados a la censura y a la represión en la isla durante el llamado quinquenio gris (1971-1976) fue un error, y de ninguna manera se trata de un cambio de política cultural asociado a la enfermedad de Fidel Castro y la presidencia interina de su hermano Raúl.

El ministro cubano de Cultura, Abel Prieto, marcó así -en entrevista con La Jornada- la posición oficial sobre el tema que en las recientes semanas ha sido motivo de intenso debate en ámbitos políticos y culturales, tanto dentro como fuera de Cuba.

De acuerdo con Prieto, los ex funcionarios que aparecieron en esos programas, durante el ejercicio de sus cargos ''no aplicaron la política cultural unitaria de este país, y por eso fue un error de la televisión presentarlos, creando esa percepción entre nuestros principales artistas y escritores".

La entrevista se realizó en un salón de las oficinas del Ministerio de Cultura, el pasado 15 de febrero. El funcionario abrió un espacio en su agenda repleta de actividades relacionadas con la Feria Internacional del Libro de La Habana, que en esos días se llevaba a cabo, uno de los principales acontecimientos culturales de la ciudad.

Debate sobre el quinquenio gris

El debate sobre el quinquenio gris comenzó a principios de enero, poco después de que aparecieron en sendos programas televisivos tres funcionarios de esa etapa: Luis Pavón Tamayo, Armando Quesada y Jorge Serguera, presentados como si hubieran hecho aportaciones valiosas a la cultura cubana.

Muchos escritores y artistas de la isla respondieron críticamente ante lo que les parecía una reivindicación de los verdugos.

El debate empezó en Internet: correo electrónico, blogs y distintos foros, y aterrizó en una amplia reunión en la Casa de las Américas, institución emblemática de la cultura oficial cubana (La Jornada, 6 de febrero).

Luis Pavón Tamayo dirigió el Consejo Nacional de Cultura (hoy Ministerio de Cultura); Jorge Serguera presidió el Instituto Cubano de Radio y Televisión y estuvo vinculado a los ''juicios revolucionarios" contra opositores al régimen; Armando Quesada se hacía cargo del área teatral. De distintas maneras los tres protagonizaron episodios de censura y represión durante el quinquenio gris.

Tras la respuesta crítica de intelectuales residentes en la isla, se llevó a cabo una serie de discusiones de integrantes de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Uneac). Al respecto, Prieto explicó: ''La dirección del partido les envió un mensaje, del que yo fui portador, en el sentido de que había sido un error la presencia en televisión de esos tres ex funcionarios. ¿Por qué? Porque hoy la dirección de este país ve muy críticamente esa etapa, por suerte breve, donde nos apartamos de la política cultural que la Revolución inauguró en 1961 y en la que se invitaba a unirse en la obra cultural a los artistas y escritores de todas las tendencias, de todas las generaciones; católicos, comunistas, incluso no revolucionarios pero que fueran honestos".

Como muestra de que ha habido una ''rectificación" de los errores del quinquenio gris, el ministro de Cultura señaló que muchos de los escritores y artistas que participaron en el actual debate y que en su momento sufrieron en carne propia la censura y la represión, hoy son ampliamente reconocidos por la Revolución, ''editan sus libros, estrenan sus obras".

Mencionó en particular al poeta, ensayista y narrador César López, a quien estuvo dedicada la edición más reciente de la Feria Internacional del Libro de La Habana. Precisamente al comienzo de la Feria, López leyó un texto crítico de la homofobia y las acciones represivas de que fueron objeto varios escritores a finales de los años 60 y principios de los 70 (La Jornada, 10 de febrero).

El respaldo del partido

En opinión de Prieto ''fue muy importante" que la Uneac contara con ese respaldo del partido: ''Se organizó un ciclo de debates en Casa de las Américas, que no estaba concebido para la prensa, al que asistieron intelectuales cubanos por invitación para debatir sobre aquellos errores: ¿en qué consistieron?, ¿qué dañaron? Pienso que después de las discusiones y los análisis ha salido reforzada la unidad de la gente en torno a nuestra actual política cultural".

La situación -observó el ministro de Cultura- provocó reacciones ''muy agresivas desde Miami" y una revista digital, Encuentro, que es financiada por la asociación derechista Nacional Endowment for Democracy (NED), ''pretendió asociar lo que fue un error coyuntural con la salud de Fidel y con el desempeño de Raúl como presidente provisional de Cuba, como si este error tuviera que ver con el funcionamiento de nuestra institucionalidad cultural".

De aspecto informal, pelo crespo largo, Abel Prieto es uno de los altos funcionarios más singulares del gobierno cubano. Su trato cortés y desenfadado rompe con la distante solemnidad de los políticos convencionales. También escritor y profesor de literatura, antes de ocupar el Ministerio de Cultura fue director de la editorial estatal Letras Cubanas y presidente de la Uneac.

Propios y extraños lo consideran un funcionario no dogmático, cuyo papel ha sido decisivo en la buena relación que actualmente priva entre las comunidad intelectual y artística de la isla con el gobierno cubano, sobre todo después de etapas como la del quinquenio gris. Se sabe que durante el reciente debate, su intervención facilitó el entendimiento entre las distintas posiciones, de un lado y otro.

Durante la entrevista, el funcionario también reflexionó sobre los distintos momentos de la cultura cubana después del triunfo de la Revolución; sostuvo que el ''realismo socialista" es ''una aberración"; reconoció que ha habido ''temas tabú" y defendió la importancia y la necesidad de la crítica.

-¿Cuáles son los principios que hoy rigen la política cultural cubana?

-Primero, una política de una extraordinaria amplitud en términos de convocatoria, que no tiene nada que ver con el sectarismo, no tiene nada que ver con el dogma.

-¿La podríamos llamar reivindicatoria?

-Podríamos usar esa palabra si la asocias a la coyuntura sectaria, pero creo que es más que eso. Tiene que ver con aquella política que se fundó en 1961, que define la cultura nacional pero no es chovinista sino que es muy abierta, tiene una vocación universal. Aquí ha estado Noam Chomsky y el propio José Saramago después de aquellas declaraciones que hizo y que fueron tan amargas. Sin embargo estuvo aquí y saludó a Fidel.

''Cuba reivindica permanentemente un pensamiento de la emancipación que tiene mucho que ver con la democratización del producto cultural, de las artes plásticas, del cine. Nos interesa un lector, un espectador, un receptor de la cultura, participativo y al mismo tiempo preparado para conocer, entender lo mejor e incluso lo más sofisticado del arte.

''La gente acude masivamente a ver el Festival de Cine Latinoamericano, los ciclos de cine europeo, o el cine estadunidense experimental, a pesar de que tenemos influencia del peor cine hollywoodense. El festival de ballet, un arte que se considera asociado a minorías, también es tremendamente masivo."

También ''tratamos de conservar la memoria, ahí está todo el trabajo que hemos venido haciendo con el patrimonio; el tema de los jóvenes es para nosotros fundamental, proteger su obra, que no se vean obligados a hacer concesiones en busca del mercado. Ahora tenemos un boom de jóvenes realizadores de cine y video, de documentalistas. ¿Cómo respaldar sus proyectos con pocos recursos?"

La industria del libro, asegura Abel Prieto, ''es un área que ya salió de la crisis, gracias al respaldo del gobierno central, pero el cine está todavía en una crisis muy grave; en la música, hemos creado un nuevo sello editorial que se llama Colibrí, para trovadores, raperos, roqueros, buscando áreas que no están tradicionalmente asociadas al mercado del disco".

Dignidad y resistencia

-¿Ya está suficientemente madura, fortalecida, la Revolución para relacionarse de otra manera con la crítica, aun en el asedio?

-La crítica y la reflexión sobre nuestros errores ha sido un estilo permanente de este país. Hay una frase de Cintio Vitier que me gusta mucho, dice: ''nuestro desafío es construir un parlamento en una trinchera". Creo que es muy obvia la necesidad del debate en las instituciones de la Revolución. Acuérdate de las películas de Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, desde La muerte de un burócrata hasta Memorias del subdesarrollo. No eran películas complacientes. Desde Memorias del subdesarrollo hasta Fresa y chocolate hay un cine revolucionario y al mismo tiempo inconforme, donde la herejía está incorporada a nivel, te diría, celular. O Suite Habana, esa obra maestra de Fernando Pérez, que es un canto a la dignidad, a la resistencia; cómo se puede ser digno en las peores condiciones, en condiciones de ruina material, la dignidad está presente.

''Tú mira nuestra literatura, desde Senel Paz hasta Leonardo Padura: la Revolución no ha fomentado un arte panfletario, propagandístico, la crítica lo ha acompañado siempre. Hay cosas que a veces no se dicen cuando se habla de nuestros poderes populares y nuestra asamblea nacional, como que un ministro está sometido sistemáticamente a discusión. Creo que la Revolución está madura y lo ha estado en otros momentos para que esa capacidad autocrítica, esa capacidad reflexiva sobre sí misma, se ejerza de manera rigurosa, sin temer a lo que puedan decir de nosotros fuera de Cuba.

''Es verdad que ha existido ese asedio de una manera permanente, pero en la cultura esa mentalidad de plaza sitiada nunca ha prosperado, ni cuando se derrumbó la Unión Soviética, en 1989. En ese tiempo estaba Armando Hart como ministro y yo era presidente de la Uneac. Recuerdo que en los peores momentos, inclusive en los de mucha incertidumbre, se discutía y se analizaba colectivamente la política cultural. Para nosotros es fundamental que el artista, el intelectual protagonice la vida de la institución."

Sí ha habido temas tabú

-¿Ya no hay temas tabú o nunca los hubo?

-Los ha habido. El tema de la homofobia, que ha estado sometido a debate en estos días porque estas personas que aparecieron en televisión realmente practicaron una exclusión de los homosexuales. Venimos de una tradición machista muy fuerte. Cuando entre a la universidad, en el año 68, conocí gente muy honesta e intelectualmente con mucha preparación, pero que eran homófonos. Eso ha ido cambiando. Cuando nació el Ballet Nacional de Cuba, que antes se llamaba Alicia Alonso, los varones hubo que buscarlos en los orfanatos porque las familias cubanas no querían que sus hijos estudiaran ballet porque eso era cosa de homosexuales. Hoy los niños que quieren entrar al ballet son varones y sus familias los llevan.

''No puedo decir que el problema esté superado, igual que los prejuicios raciales. Tú puedes barrer con las bases institucionales del racismo y de la homofobia, pero prevalece en algunos sectores."

-¿Para el gobierno cubano qué representa hoy el término realismo socialista?

-Eso es una aberración y convertirlo en política oficial fue uno de los grandes errores que se cometieron en la Unión Soviética y en los demás países del bloque soviético. El Che Guevara, en El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba, es implacable con esa idea, porque asocia el realismo decimonónico con las ideas del socialismo. Es una locura. Y Fidel, en Palabras a los intelectuales, se separa radical, tajantemente, de ese tipo de concepto. Aquí hubo gente que lo quiso imponer y ahora se le ve como una historia triste de errores esenciales que se cometieron en esos países en el campo de la cultura y que le hicieron daño a la legitimidad de esos procesos.

-¿Cómo hay que leer hoy aquella frase ''Dentro de la revolución todo, contra la revolución nada"?

-Ese es un momento, una frase dentro del discurso que se conoce como Palabras a los intelectuales. Lo que pasa es que cuando tú sacas eso y lo conviertes en un eslogan, la gente dice bueno, y quién interpreta lo que está dentro y lo que está contra. El propio Fidel dice que incluso dentro de la revolución tiene que haber un espacio para que trabajen en la cultura y colaboren con nuestra obra cultural inclusive aquellos intelectuales que no se consideren revolucionarios. Es decir, el dentro no es exclusión, es convocatoria amplísima a todas las tendencias. Después los exégetas, en nombre del dogma, traicionaron ese discurso.